Now she had made her remark about being innocent, and he made his decision. He cleared his throat and in a loud voice said, “Now then, Miriam, are you free next week to take over from Sadie? She’s off whooping it up on the Costa Brava, leaving me in the lurch. Could you fill in for the week?”

Miriam felt the blood rising to her cheeks. She could have kissed him. With tears in her eyes she said of course she’d be glad to help him out. She’d come in for a pound of tomatoes, please. She was going to try her hand at a risotto, she said, for an important guest.

“Then you’ll need some of my Italian ham,” he said in an artificially jolly voice. “Gives it the authentic taste.”

One of the gossips asked audibly if her friend had tried Farmer Jones’s ham on the bone. “Fresh English produce is good enough for me,” she had added, and left the shop swiftly, calling over her shoulder that next week she thought she’d go to the supermarket in town, just for a change.

Miriam drooped. “Are you sure you want me?” she whispered to Will.

“Quite sure,” he said angrily. “I’ve a good mind to bar that woman from the shop.”

Miriam shook her head. “You’d have to bar most of the village,” she said sadly.

DEIRDRE HAD ARRIVED late at the social services offices, and crept into the back of the room. She was seen, of course, and the woman chairing the meeting welcomed her with exaggerated pleasantness. “ So glad you could make it, Deirdre,” she said.

After the meeting was over, there was coffee and chat, and Deirdre looked around for the person she knew could help her with fostering questions.

“It’s a long time ago, I know,” she said. “But would it be possible to look up records of who was fostered and with what family, dating back to the nineteen seventies?”

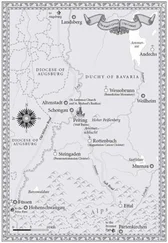

“Bit before my time,” the woman answered. “In this area, was it?”

Deirdre said no, over the other side of the county, in and around Oakbridge. The woman shook her head. “Can’t help you, sorry,” she said. Then she brightened. “I know,” she added, “there’s a man over there-he gave us a little talk before you arrived-all about his experiences of social work in the old days.”

“How old?” said Deirdre, beginning to feel like Mrs. Methuselah.

“Go and ask him,” urged her friend. “He’s a nice old boy, and I’m sure could help you. Go on, Deirdre, you know how senior citizens like to talk about olden times.”

Well, nothing ventured, thought Deirdre, and pushed her way through the chattering crowd to where a tall, heavily built man stood talking to a dutiful couple of social workers. He was probably in his seventies, and looked friendly. When she said she was sorry she had missed his talk, but wanted to pick his brains, he twinkled at her with a promising sparkle in his eyes.

“Oakbridge, did you say?” He was interested, and flattered that this attractive woman had sought him out. “Got my first job there,” he said, smiling at the memory. “Just a young chap then, full of high ideals and hopes for a better future for mankind!”

“Did you have anything to do with fostering?” Deirdre said.

“Oh yes,” he said. “We had to take in all the various departments. Are you trying to trace somebody?”

What a piece of luck, Deirdre said to herself. “I’m interested in a woman who disappeared leaving two children alone in a flat. Seems they never found out where she’d gone, and the children were taken into care. The only name we’ve got is Bentall.”

“ Bentall ? The Bentall case? Good God, I certainly remember that. It was a real scandal at the time. The mother who disappeared was the only daughter of the mayor. Old Buster Bentall, we used to call him. Made his fortune out of speculative development. But that was a long time ago,” he added. “What exactly did you want to know?”

Deirdre said that anything he could remember would be useful. It appeared he remembered the girl getting pregnant, going away and returning without a baby later on. Then she’d got married, he thought, and suddenly a child, a girl, appeared from nowhere, and she’d had another by the husband.”

“What a memory!” Deirdre said.

“Photographic, the wife says,” he replied modestly. “I can see old Buster Bentall now. Bit of a bully, red-faced and little piggy eyes. He’d not get away with it these days.”

“With what?” Deirdre said.

“Making his money that way when he was in mayoral office. Had friends in the planning department. You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours. You know the kind of thing.”

“Anything more about the abandoned girls?”

He rubbed his chin. “There was something. Came up later on, but I was about to start a new-Oh, I remember!” he said, beaming. “Although the mother never reappeared, the man she married was in the news a few years later. Robbery with violence. And he had form, apparently. Nasty piece of work, I reckon. No wonder she went missing!”

Deirdre held her breath. “Do you remember his name?” she squeaked.

“Oh, yes. He came from the worst family in Oakbridge. They were Jessops. Generations of no-goods, and he was reckoned to be the worst. Buster Bentall cut them off when they married. Wouldn’t have his daughter or her husband in his house. His poor wife was heartbroken. The girl was an only child, you see.”

“Now then, Deirdre,” a loud voice came from behind them. “You mustn’t monopolise our distinguished guest! Come along, now, I want you to meet my assistant. She so much enjoyed your talk.”

“Sod it,” muttered Deirdre, as they walked away. Still, she had probably found out most of what he remembered, and it was pure gold.

IVY SAT UP in bed, and felt a sharp pain in her lower back. She tried to ignore it, and swung her legs over the edge of the bed in order to stand up. The pain shot through her, and she gasped. Finally it subsided, and she managed to reach her chair to sit down. Well, what did she expect? She had insisted on pushing a wheelchair over rough paths and down a grassy lane. Roy had said he thought it was too much for her, but she had insisted.

Stubborn, said her mother’s voice in her head. Always were and always will be.

“Go away, Mother,” said Ivy, not noticing her door was ajar. A voice answered her.

“It’s only Katya, Miss Beasley. Are you all right? You need some help?”

“Come in, girl, come in,” Ivy said, wincing as she settled in her chair.

Katya came in, and saw at once that Ivy was not all right. She was pale, and frowned as she moved to reach for her handkerchief.

“Do you have pain,” Katya asked anxiously.

“A little. Just a twinge in the back. Often get it,” Ivy said, and added that old age was sent to try us, and she did not intend to let it get the upper hand.

“Shall I get Mrs. Spurling? Or Miss Pinkney? Would you like some painkilling tablets?”

Ivy eventually convinced Katya that she was perfectly all right, and if she could just sit quietly for a few minutes the pain would go. A cup of strong, hot tea would be just the ticket, she said. Perhaps she could have breakfast in her room.

She did indeed feel much restored after she’d eaten porridge, bacon and egg, and drunk three cups of tea, and even managed to dress herself without help. She knew from experience that the best thing to do with a painful back was to walk steadily for half an hour or so to loosen it up. She telephoned Deirdre to say she would be coming up for an early coffee. “On foot,” she interrupted, as Deirdre offered to collect her. She was encouraged to hear Deirdre say with genuine pleasure that she must stay for lunch, and then they could have a good talk. “I’ve got something very interesting to tell you, Ivy,” she said.

Читать дальше