“For what?”

“Oh, shit, you know. For all of mankind. The whole human race.”

* * *

Back on Albin Street I look up at the sun. The city is hotter than it was last week, and you can smell it on the air—the reek of untreated sewage water drifting up off the river, of garbage that’s been dumped in the streets and out of windows. Sweat and body odor and fear. I should go home and change clothes, see if any damage has been done while I was away. Make sure that nothing has been taken from my store of food and supplies, all that we left behind.

“We really should, buddy,” I say to Houdini. “We should go home.”

But we don’t. We go back the way we came, down Albin, down Rumford, up Pleasant Street.

What few people there are on the streets are moving quickly, no eye contact. As we get closer to Langley Boulevard a man rushes past in a windbreaker, head down, carrying two whole hams, one under each arm. Then a woman, running, pushing a stroller with a giant Deer Park bottle strapped into it instead of a child.

I realize suddenly I have not seen a police car or a police officer or evidence of police presence of any kind since I returned to Concord, and for some reason the observation floods my stomach with a churning dread.

My legs are getting tired; my busted arm joggles against my side, tight and uncomfortable and useless, like I’m lugging a ten-pound weight around, to prove a point or win a contest.

* * *

I find Dr. Fenton right where I left her, working her way down her towering pile of charts, leaning against the counter of the nurses’ station, her eyes blinking and red behind the round glasses.

“Hey,” I start, but then another doctor, short and bald and bleary eyed, stops and scowls. “Is that a fucking dog? You can’t have a fucking dog in here.”

“Sorry,” I say, but Fenton says, “Shut up, Gordon. That dog’s more hygienic than you are.”

“Clever,” he says, “you fucking hack.” He disappears into an adjacent exam room and slams the door. Fenton turns to me. “What happened, Detective Palace? You get shot again?”

* * *

We take the unlit stairwell down to the crowded first-floor cafeteria: dirty linoleum tables and a handful of stools, a big plastic bin filled with mismatched cutlery, boxes of supermarket teabags and a row of kettles lined up on camp stoves. Dr. Fenton and I take our tea out to the lobby and sit in the overstuffed chairs.

“When did you stop working in the morgue?”

“Two weeks ago,” she says. “Three, maybe. The last month or so, though, we weren’t doing autopsies. No call for it. Just intake, preparing bodies for burial.”

“But you were still down there when Independence Day happened?”

“I was.”

The front door of the hospital crashes open and a middle-aged man stumbles in carrying a woman in his arms like a newlywed, her bleeding profusely from the wrists, him just yelling, “God you idiot, you idiot, you’re such an idiot!” He kicks open the door of the stairwell and lugs his wife inside, and the door slams closed behind them. Fenton lifts her glasses to rub her eyes, looks at me expectantly.

“I’m trying to I.D. a corpse that came in that night.”

“On the Fourth?” says Fenton. “Forget it.”

“Why?”

“Why? We had three dozen corpses at least. As many as forty, I think. They were stacked like firewood down there.”

“Oh.”

Stacked like firewood . My neighbor, sweet Mr. Maron of the solar still, he died that night.

“We weren’t able to process them properly, is the other thing. No photographs, no intake records. Just bagging and tagging, really.”

“The thing is, Dr. Fenton, this particular corpse would have been rather distinctive.”

“You, my friend,” she says, tasting her tea with a moue of displeasure, “are rather distinctive.”

“A man, thirties probably. Gold-capped teeth. Humorous tattoos.”

“How so, humorous?”

“I don’t know. Zany, somehow.” Dr. Fenton is looking at me bemusedly, and I don’t know what I had imagined: a tattoo of a rubber chicken? Marvin the Martian?

“Where on the body?” Fenton asks.

“I don’t know.”

“Do you know the means of death?”

“Weren’t they all—gunshots?”

“No, Hank.” The words are dry with sarcasm, but then she stops, shakes her head, continues quietly. “No. They weren’t.”

Dr. Fenton takes off the glasses, looks at her hands, and in case I am correct in my impression that she is silently weeping I avert my gaze, try to find something interesting to look at in the dimness of the hospital lobby.

“And so,” she says abruptly, shifting back into her characteristic tone, “the answer is no.”

“No, there wasn’t anybody matching that description or, no, you don’t recall?”

“The former. I am relatively certain we did not see a body matching that description.”

“How certain is relatively certain?”

Dr. Fenton thinks this over. I wonder how it’s going upstairs for the desperate man and his wife, bleeding from her wrists, how they’re faring under the charge of Dr. Gordon.

“Eighty percent,” says Dr. Fenton.

“Is it possible a victim might have been taken to New Hampshire Hospital?”

“No.” she says. “It’s closed. Unless someone took a body there and didn’t know they were closed and dumped it in the horseshoe driveway. I understand—” She pauses, clears her throat. “I understand some bodies have been deposited in such a way.”

“Right,” I say absently.

She stands up. Time to get back to work. “How’s the arm?”

“So-so.” I squeeze my right biceps gingerly with my left hand. “I don’t feel much yet.”

“That’s appropriate,” she says.

We’re walking back to the stairway. I set my half-empty teacup down carefully on the floor next to a full garbage can.

“As circulation improves over the next couple weeks, you’ll start to get a persistent tingling, and then you’ll need physical therapy to work toward regular functioning. Then, around early October, a massive object will strike Earth and you will die.”

“So I go over there on Friday night, maybe two hours after you take off, and the playground is a no-man’s-land. The swings are cut down, just chains dangling, you know? The fence is kicked over, and the—what do you call it?—the jungle gym, it’s over on its side. I’m thinking maybe I’ve got the wrong place.”

“You’re at Quincy Elementary?”

“Yeah,” says Detective Culverson. “Quincy. The play field behind the school.”

“That’s right.”

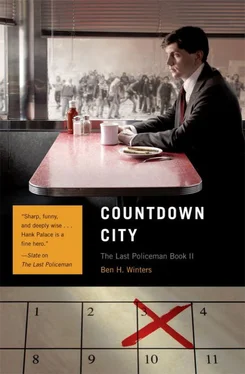

The diner; the booth; my old friend with an unlit cigar, stirring honey into his tea, telling me a story. A fat double-bread-loaf indentation in the vinyl where McGully used to sit.

“So there I am like a dummy, holding this samurai sword. And don’t even ask how I got it, by the way. I’m standing there and I’m thinking, Okay, so, Hank’s little buddies have moved along, they’ve found some other squat. But then I see that there’s a flier: If you are the parent of… You know? One of those. It looks like they got scooped up.”

I exhale. This is good news. This is the best possible outcome for Alyssa and Micah Rose. A mercy bus came and took them somewhere indoors, with food and organized play and prayer circles three times a day. Ruth-Ann is sitting at a stool by the counter. She’s got her hot-water carafe, her pens arranged behind her ear, her little order notebook jutting out of the front pocket of her apron. Culverson is in his undershirt, off-white and yellowed and stained at the pits, because he’s lent me his dress shirt, which puffs out at my stomach and gaps at the collar.

Читать дальше