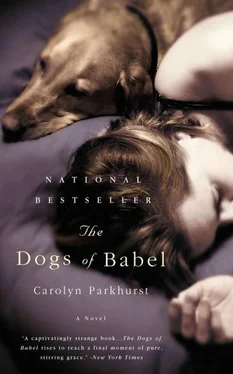

Carolyn Parkhurst - The Dogs of Babel

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carolyn Parkhurst - The Dogs of Babel» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Dogs of Babel

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-7595-2806-2

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Dogs of Babel: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Dogs of Babel»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Dogs of Babel — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Dogs of Babel», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The second anomaly has to do with Lorelei. As far as I can piece together, it seems that Lexy took a steak from the refrigerator, one we’d been planning to barbecue that night on the grill, cooked it, and gave it to the dog. At first I thought she must have eaten it herself and merely given Lorelei the bone to chew on—I found the bone several days later, hidden in a corner of the bedroom—but the thing is, there were no dirty plates or cutlery, only the frying pan sitting on the stove where she left it. The dishwasher was locked, having been run that morning after breakfast, and when I opened it up, I could still recognize my own handiwork in the way the dishes had been negotiated into place. The dishwasher hadn’t been touched, the dish rack next to the sink was empty, and the dish towels weren’t even moist. I have to conclude that one of two things happened: either Lexy surprised Lorelei with an unprecedented wealth of meat or she stood in our kitchen on the last day of her life and ate an entire twenty-ounce steak with her fingers. As I think about it now, it occurs to me that there might be a third scenario, and it might be the best one of all: perhaps the two of them shared it.

Maybe these events mean nothing. After all, I am a grieving man, and I am trying very hard to find some sense in my wife’s death. But the evidence I have discovered is sufficiently strange to make me wonder what really happened that day, whether it was really a desire for apples that led my sweet wife to climb to the top of that tree. Lorelei is my witness, not just to Lexy’s death itself but to all the events leading up to it. She watched Lexy move through her days and her nights. She was there for the unfolding of our marriage from its first day to its last. Simply put, she knows things I don’t. I feel I must do whatever I can to unlock that knowledge.

TWO

Perhaps you’re familiar with some of the more celebrated cases of language acquisition in dogs, but allow me to provide a brief history to refresh your memory. First off, of course, is the case of the sixteenth-century child-dog of Lyons. This dog, by most accounts a keeshond brought into the area by Dutch traders, was adopted at birth by a grieving mother whose baby had died soon after childbirth. The woman suckled the dog like a child and dressed him in little nighties and bonnets. As the pup grew, his “mother” took great pains to teach him to speak and succeeded to some degree by sheer perseverance, though listeners often had to ask the woman to translate. The dog became a celebrated member of the community but never learned to frolic and play like other dogs. The dog and his mother lived happily together for thirteen years, until the woman grew ill, and when she lay on her deathbed, the dog never left her side. On the night the woman closed her eyes for the last time, the dog spoke his last words: “Without your ear, I have no tongue.” (I need hardly point out the double meaning of both the English “tongue” and the French langue, which refer both to the physical tongue and to language.) Though the dog lived another year after his mother’s death, he never made another noise, either canine or human. After his death, the people of Lyons erected a statue in his honor, with his final words engraved on the base.

I think this story, so full of fairy-tale magic and sadness yet so well documented by the greatest scientific minds of their age, will be the perfect opener for my book, my earnest and scholarly work in which I try to explain to my baffled colleagues why, after twenty years of devoting my time to the study of linguistics, I have decided to turn my energies to teaching a dog to talk.

I’ll need to begin with case histories to prove that I at least cracked a book before going completely off the deep end. They’ll want me to remind them of the strange case of Vasil, the eighteenth-century Hungarian who, influenced by a philosopher named Geoffrey Longwell, who believed that dogs were the lost tribe of Israel, performed a series of experiments on a litter of vizsla puppies. Vasil took as his inspiration the biblical story of the Garden of Eden; though the Bible is unclear as to whether there were dogs in Eden, Vasil concluded that God would certainly not have omitted such a fine species of animal. Taking as evidence the serpent’s speech to Eve, Vasil postulated that all animals must have been blessed with the power of speech in the earthly paradise, a power they lost when Adam and Eve left Eden. He felt that if he could restore that power, which had been unfairly wrested from the animals, he would uncover the first language ever spoken.

To recapture this language, Vasil placed each puppy in a walled-off garden, each one separate from its brothers and sisters, and attempted to re-create the conditions of Eden. He provided them with plentiful food and water, and he massaged their throats daily to encourage speech. He met with varied success. One puppy never spoke at all, one made sounds that resembled a mumbled French (although later researchers found it to be an Alsatian creole), and one learned only the Hungarian word for roast beef. The remaining five puppies merely barked, although they all seemed to understand one another.

Vasil’s theories drew condemnation from the Church, especially his premise that God had acted unfairly in revoking dogs’ powers of speech, and he spent the last twenty years of his life in prison. The vizslas were instrumental in his arrest; the dogs escaped and ran through the streets, with the French-speaking one barking out naughty and insulting limericks and the Hungarian-speaking one calling for roast beef, until the amazed crowd followed them to Vasil’s house.

The real clincher, I think, will be the tragic case of Wendell Hollis, which, my colleagues will certainly recall, is the most prominent example of this kind of inquiry in the modern era. Over a period of several years, Hollis performed surgery on more than a hundred dogs, changing the shape of their palates to make them more conducive to the forming of words. Several of the dogs died as a result of the surgery, which Hollis performed in his New York apartment, and many of the others ran away. Hollis was arrested after the police received a complaint about the noise; after years of putting up with the mangled barking, a neighbor called the police when one of the dogs learned to cry for help. This one dog, with a scarred throat and misshapen mouth, testified at the trial. Though he didn’t speak in complete sentences, he was able to say “hate” and “fire pain” and “brothers gone away.” The jury took only one hour to reach a verdict, and Hollis was sentenced to five years in prison.

None of these cases can be considered completely successful, of course. But it’s the very form these failures took, the “almost” quality of each half success, that makes me think there’s more in this area to be explored.

In fact, I find lately that I can think of nothing else.

But if I am to keep my good name in the academic community, something I’m no longer sure I care about doing, I can’t allow such subjectivity. I have to begin by telling my colleagues that there’s a whole body of work out there already, nearly as old as the study of language itself. I have to tell them that I’m not doing anything new at all.

If I could, though, I would begin the way poets used to do when they told their stories of love and war and troubles rained down from the heavens. I would begin like this:

I sing of a woman with ink on her hands and pictures hidden beneath her hair. I sing of a dog with a skin like velvet pushed the wrong way. I sing of the shape a fallen body makes in the dirt beneath a tree, and I sing of an ordinary man who wanted to know things no human being could tell him. This is the true beginning.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Dogs of Babel»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Dogs of Babel» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Dogs of Babel» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.