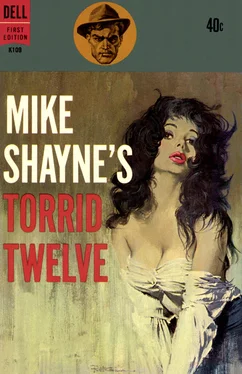

Brett Halliday - Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brett Halliday - Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1961, Издательство: Dell Publishing, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:1961

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He was still trying to place it when Mr. Porter, with a snort of savage disgust, said: “Then, just this morning, this came!”

Lifting the carton from his lap, he removed the lid. Revealed was a plastic Danjuro doll — fat and egg-shaped, the sort with weighted bottom which, when tipped over, bobs up again. Some four inches high, its body was painted to represent an exotic costume of the popular Kabukiza theatre.

Peter remembered a silly Japanese joke which labeled some geishas Danjuro because they were pushovers. Then he noticed that this doll was not of traditional type. Instead of being sealed at the stomach where the halves joined, the two half-eggs screwed together. Even more radical was the departure in the face. Instead of Danjuro’s, the famous actor, the expression was outrageously comic: squint-eyes, mouth drawn at one corner in a leer which, for all its grotesquerie, yielded a tender human appeal.

“Porter Play’s Best-Seller.” That was how Life had described it.

“Only damn thing in normal production,” Mr. Porter grunted. “But that’s not the point.” Lifting the doll from its box he touched the head. It had been twisted off, then taped back at a crooked angle to appear as a broken neck. In the box was an unsigned warning: Mr. Poter go hom.

Peter whistled softly. Unconsciously, Mr. Porter was massaging his throat. At last he said: “I’m no coward. I was in war myself in ’seventeen. But when you come up against something you don’t understand, that’s when you worry. And you can’t do a blame thing. I’d already the queerest feeling I wasn’t welcome. In my own plant, mind! But until this came I thought it just could be my imagination. Strange land, and forced to depend on an interpreter who might or mightn’t be reliable.” He eyed Peter with speculation. “Say, didn’t I hear you talking Jap to the maids?”

This, Peter recognized, was an oblique invitation. And far from resenting it, he smiled at his own self-deception in thinking that ever he could survive a quiet holiday. Truth was, he sensed a much more extraordinary story than had yet appeared in print.

“Oh, yes,” he said comfortably, “I know Japanese. It’s a rather chameleon language, quite like the people and loaded with double meanings. If I could be of help—” He produced his card.

Most strangers, on learning Peter Ragland’s identity as the famous foreign correspondent for the North newspapers, were properly impressed. It was possible Mr. Porter was, too, but sheer relief outweighed his curiosity.

“Would you?” he said, the worry receding before a pathetically eager smile. “Would you really? You can’t know what it would mean — another American who knows the score back-stopping me.”

They drove, in Mr. Porter’s company sedan and at Peter’s wish, to the National Rural Police jail where Tanizaki Hajime was held.

“Though I don’t see what good it can do,” Mr. Porter objected, parking the car. “I was here myself, you know, and he wouldn’t even see me. Sent out word he hated our guts.”

He switched off the ignition. “A fine thing, after all John did for him. The trip to America, good job, good pay, bonus at New Year’s, favors for his family. Dammit! How can a man be so thankless as that? And yet it’s just the reason the police think he killed John.”

“The hate?” Peter had his hand on the door handle.

“More what led up to the hate. Because he’d done so well with us. They said John was Tanizaki’s ‘on- man.’ Now what sort of stuff is that?”

Peter relaxed in the seat. This would take some explaining. “Have you ever,” he asked, “heard of Lafcadio Hearn?”

“Writer fellow who married a Nip? Oh, yes.”

“It was his idea that to understand these people you have to learn to think all over again; backward, upside down, inside out.”

“Hmph. I’ll buy that.”

“But perhaps John didn’t,” Peter said. “Or he’d have been less likely to heap favors on Tanizaki. You see, they’re an abnormally sensitive lot. They think that when they’re born they inherit a stupendous debt from the past — to their ancestors, parents, the whole world. Then, as they go through life, these debts increase — to teachers, friends, employer, whoever helps them along. No such thing as a self-made man in Japan. Life’s a joint enterprise.”

“Ha?” Mr. Porter, as a self-made man himself, scoffed at a concept so utterly alien.

“These debts are on,” Peter continued. “And to be a really virtuous man, you have to spend your life sacrificing everything you’d rather do to pay back. So naturally when somebody comes along and does you a gratuitous favor, as John did, it’s that much more load to repay and you resent it.”

“My stars! You don’t mean it could reach the point of murder?”

“It’s a pretty terrible thing,” Peter said thoughtfully, “when a Japanese at last realizes he can never pay off. It’s loss of face, end of the line. On is their guiding force. Debt. Burden. Sacrifice. You owe. You owe it to your name, for instance, to keep it spotless. That’s why it’s a Japanese virtue to revenge insult. And one insult is to be given something you can’t pay back.

“Tied in with that is the fact you’re not supposed to change stations in life. You owe it to your name to stay put. So it’s just possible that, besides feeling insulted, Tanizaki figured he was getting above himself and blamed John for it.”

An austere old man in black kimono, with the thinning white beard and high black skull cap of a patriarch, appeared from the jail and walked slowly down the steps. On seeing the company car, he paused in recognition and, a fierce expression darkened his face. Then, abruptly, he turned and moved off.

“Tanizaki’s father,” Mr. Porter said. “Dammit! I can sure feel for him!”

Peter watched the old man out of sight. He had seen the type often — hard-bitten traditionalists who ruled their families with an iron fist, picking wives for the sons and husbands for the daughters.

“Tanizaki lives with him? Of course. It’s the on he owes. And because of it, he must always obey his father’s every wish.”

Mr. Porter was incredulous. “A grown man like Tanizaki? It must drive these people nuts.”

Peter was grinning as he stepped out of the car. “Yes, but like everywhere else, there are always backsliders.”

He recalled his little lesson a few minutes later when Tanizaki, gravely accepting a cigarette, murmured, “Arigato.” One of the innumerable terms for “thank you,” but it also meant: “How difficult for me to become indebted to you for this; I am ashamed.”

Peter knew that the solemn-faced Tanizaki also must be desperately ashamed of being under arrest. Haji, this shame was, a far greater punishment than death itself. For in death, there was nothing; finis, no hell, no heaven. But the shame was now and lay heavily on his honor.

Which was why Tanizaki’s reaction surprised Peter when he urged: “But why not say where you were that night?”

Six unaccounted hours, for from the factory Tanizaki had not reached home till midnight.

“Odawara?” suggested Peter. “Maybe you have a geisha in Odawara?”

After all, if a prosperous young Japanese wanted to keep a geisha, who cared? But Tanizaki merely stared at the cell wall.

“Don’t you know,” Peter persisted, “that it would be so much easier if you explained where you were?”

“Then I would be let free,” Tanizaki said.

“Certainly, if you proved you were somewhere else.”

“In such case, no, I stay here,” Tanizaki said flatly. Was there a glint of fear in those dark, slanted eyes? Fear of something on the outside so strong that it compelled him to accept the shame of arrest? Unable to penetrate the expressionless mask of this young Oriental face, Peter — quite in Japanese fashion — approached the problem sideways.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mike Shayne's Torrid Twelve» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.