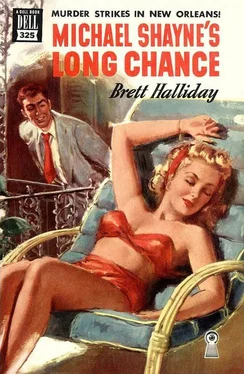

Brett Halliday - Michael Shayne's Long Chance

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brett Halliday - Michael Shayne's Long Chance» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1949, Издательство: Dell Books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Michael Shayne's Long Chance

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1949

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Michael Shayne's Long Chance: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Michael Shayne's Long Chance»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Michael Shayne's Long Chance — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Michael Shayne's Long Chance», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Brett Halliday

Michael Shayne’s Long Chance

Chapter one

Michael Shayne’s gray eyes were bleak, his face was set in gaunt lines, his bushy red brows were drawn together over a vertical furrow which had deepened during the past two months. He dumped the last of the junk from the steel filing cabinet into a huge cardboard box. The battered oak desk was cleared of a useless accumulation of papers and what-not, and the small first-floor apartment which had served him as an office for nine years was littered with boxes and wastebaskets, waiting for the trashman.

The spacious corner apartment on the floor above, where he had spent many happy months with Phyllis, was vacant, awaiting new tenants.

Shayne stood in the middle of the muss and rumpled his bristly red hair. Lying atop one of the boxes was a short piece of rubber hose which he had snatched from a girl’s mouth: the Lenham case. A fake kidnap note that had sent a woman into screaming hysteria was torn to bits in the wastebasket: the Hanson case. A pile of telegrams, scribbled notations, the blackjack wrested from Pug Myers that stormy night down on the Florida Keys — relics which had once held such deep significance were now mere rubbish.

There was a butcher knife which he had picked up from the floor of Phyllis Brighton’s bedroom after finding Mrs. Brighton in bed with her throat slit. The knife was sticky with human blood that night, but now it shone clean and keen-edged lying beside the rubber hose in the box marked for a scrap heap.

Shayne’s eyes kept going back to the knife. It marked the beginning of something that was ended.

He swore savagely and swept up a glass of cognac from the desk, took a deep drink and chased it with ice water. It was Monnet cognac, his last carefully guarded bottle. He had been saving it for a special occasion. Well, this was a special occasion. His suitcase was packed. He was saying good-by to Miami, giving up everything he had built over a period of nine years.

He said, “To hell with it,” aloud. He emptied the glass and poured another drink from the squat bottle, then held the bottle up to the light. A little better than half full. Might be enough to get drunk on, if he weren’t sure he would never be able to get drunk again.

The wall telephone shrilled as he set the bottle down. He turned to glower at the faithful instrument which had brought him so much good news and so much bad news during the years.

He lifted the glass of cognac and carried it to the west window, ignoring the insistent ringing of the phone. His right thumb and forefinger gently massaged the lobe of his left ear as he stood gazing at the bright sheen on the gray-purple waters of Biscayne Bay. It was noon, and trade winds waved the fronds of coco-palms and sent tiny ripples shimmering across the water.

The telephone stopped ringing after a while. He sipped the smooth aged cognac slowly and thoughtfully. He listened absently to the elevator stopping at the first floor and heard footsteps in the hallway.

The footsteps stopped at his open door. Shayne stubbornly kept his back turned. His eyes were morose and his jaws were tightly clenched as he stared steadily through the window at the familiar scene.

Timothy Rourke’s voice spoke from the doorway, a determinedly cheerful voice. “Why the hell don’t you answer your phone?”

Without turning his head, Shayne growled, “I didn’t want to be bothered.”

“Getting drunk?” Rourke walked into the room, followed by another man. Rourke stared around the disordered room, his lean face grim. His body had the hard leanness of a racing greyhound; his eyes were intelligent and kindly. He was an old hand on the Miami News, had covered Shayne’s cases for nine years and garnered many scoops.

Shayne said, “I’d get drunk if I could.” He did not turn from the window.

Rourke moved up behind him and clamped his hand on the redhead’s shoulder. “You’re nuts, Mike. Going through all this old stuff — raking up memories.”

Shayne said, “I’m through. I’m going back to New York.”

Rourke’s thin fingers bit into his shoulder. “I brought you a client.”

“I told you I was through.”

“You’re nuts,” Rourke said again, emphatically. “You need to get to work. Hell, Mike, it’s been months since Phyl—”

“I’m getting out of Miami,” Shayne interrupted harshly.

“Sorry,” Rourke said, then went on in a brisk tone. “That’s a good idea, Mike. Get the hell out of town for a while. Now this client—”

“I’m not taking any clients.” Shayne gestured jerkily toward some bits of paper strewn on the floor. “There’s my Florida license.”

“Fair enough.” Tim Rourke grinned. “Precisely why I have brought my friend to you.”

Shayne turned slowly. His eyes were bloodshot and there was a bristle of red beard on his face. He looked past Rourke and met the uneasy eyes of a slight, mild-featured man who wore a pince-nez and a harassed frown. His double-breasted business coat was buttoned tightly, and he wore a stiff collar and a bow tie.

Rourke said, “This is Joe Little, Mike. J. P. Little,” he added, with emphasis on the initials. “Meet Mike Shayne, Joe. He’s just the man you need.”

J. P. Little took a step forward and hesitantly held out his hand. His hand dropped to his side and he closed his thin lips firmly over whatever he planned to say in greeting.

Tim Rourke laughed with false heartiness and said, “Mike’s just a diamond in the rough, Joe.” He turned to Shayne. “Now see here, Mike, Mr. Little has a case that’s made to order. Just the sort of thing you go for — name your own fee and all expenses paid. Right, Joe?” He beamed upon the smaller man.

“I am prepared to pay any fee in moderation,” Mr. Little answered, and his Adam’s apple disappeared for an instant below his stiff collar.

“There you are, Mike. You want to shake the Florida sand out of your shoes. You need a case to take your mind off — things. How does New Orleans strike you?”

Shayne shrugged. “New Orleans is all right.” His tone intimated that New Orleans was the only thing that was all right.

Rourke hastily dumped a pile of rubbish from a chair and shoved it toward his friend, emptied another of a tier of boxes and took it for himself. “Mr. Little is a magazine editor,” he confided to Shayne. “He’s in Miami to interview an author about an important serial.”

Shayne hooked his right hip over a corner of the desk and said, “Honest to God, Tim, I’m not ready to take a case.”

“You can help a friend of mine. At least you can listen to what he has to say, dammit. Go ahead and tell him about it, Joe.”

Mr. Little took off his pince-nez and polished the lenses. His pale-blue eyes squinted at Shayne, then at Rourke. “If Mr. Shayne is not interested—”

“He’ll get interested,” Rourke promised. “Go ahead. I’d like to hear all of it, myself. You’ve given me only a bare outline.”

“Very well.” Mr. Little replaced his glasses and stopped squinting. “It’s about my daughter, Barbara. She’s — I’m afraid she may be in danger — in desperate need of protection.”

“Your daughter is in New Orleans?” Shayne bent forward, then scowled, angered at himself for showing interest.

“Yes. I’d better start at the beginning. You see, Barbara is the reckless type. She is headstrong and willful. I don’t understand her at all.” He made a gesture of defeat with his well-kept hands. “Perhaps it has been my fault for having lost contact with her. Her mother died when she was a baby. I’ve tried to be both mother and father, but — the press of business—” He stopped talking and held his mouth tight for a full minute.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Michael Shayne's Long Chance»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Michael Shayne's Long Chance» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Michael Shayne's Long Chance» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.