I followed my regular routine, stopped first at the mikvah which was buzzing. It was a perfect setting for murder, an underground hell, where locker room odors envelop you on entrance through the unassuming side door. Hurrying down the stone stairs and long tiled hallways, the curl and drip of the waterlogged vapors take over and then the low rumble of bass and tenor voices. At the entrance to the lockers, the bath attendant hands you your towel, one per person, and you move along toward your designated locker and the bench in front of it. You undo your shoes, remove your socks, left foot first, then the left leg of your pants, and so on, in the order in which you were taught to undress. Dressing, you reversed it, right foot first, insuring against the possibility of getting the day off on the wrong foot. And still the act of undressing provokes other indiscretions. While your hands are at work, your ears don’t remain idle. They tune into the nearest conversation in the aisle, then onto the next nearest, and so on, staying with each one long enough to hear whether it’s of interest. And of course there always is something of interest, a bit of information, gossip someone heard at home the night before, husbands picking up at the mikvah where their house-bound, child-bound, telephone-addicted wives left off the night before.

I didn’t have to wait long to hear my own name, and then the name of the man I’d fingered, Reb Shloimele, the chief administrator of Szebed, though to hear the talk, not for much longer. A well-respected man of the community the day before, today his name was mud. With the generous helping of hyperbole typical of mikvah gossip, someone equated Reb Shloimele’s crime with that of the biblical Amelek’s, Israel’s oldest enemy. In other words, Reb Shloimele was a sentenced man.

This time I expected the crowds, and the journalists with cameras. And I knew how much Szebed would hate it. The rabbis wouldn’t approve. No one would like it, but the publicity would serve to protect me. I pulled the brim of my hat down to conceal my face and made my way through the throng. Questions, microphones, and cameras were pressed on me. I walked straight through, succumbing to none. The Internet had done the work, the chat rooms had been devilishly successful; it was enough. I had no reason to add fuel to the fire and further enrage the sitting judges.

Inside, without much of a greeting and none of the usual friendly handshakes, two men attempted to lead me, strongarm style, to my place at the table, completely unnecessary since on my own I’d shown up at the courtroom. I shook them off and walked alone, pulled out the chair, sat. The judges frowned, but said nothing. They were pretending at busyness, each taking a turn at thumbing through a pile of continuous-feed paper in front of them, the tabs and holes that fit a dot matrix printer’s sprockets still attached. Someone had provided them with a complete printout of the chat room conversations, a fat manuscript titled “Hasidic Noir.” I suppressed a smile.

Throat-clearing and short grunts indicated the start of proceedings. One judge asked whether the defendant knew what he was accused of.

No, I said. As everyone here knows, I am a God-fearing, law-abiding Hasid whose livelihood is detective work. I solve petty crimes, attempt to bring to justice those who break the law, my small effort at world repair.

There was a long pause. Read this then, the judge said, and handed me a sheet of paper.

The complaint against me: libel, for attempting to besmirch a man’s name, to ruin a reputation.

The rabbi sitting directly across the table waited for me to finish reading, then said, You know as well as we do that a man guilty of libel must be judged, according to Jewish law, as a murderer. Destroying a man’s reputation is a serious crime.

I nodded and said, I’m well aware of that law because it is precisely what I believe Reb Shloimele guilty of.

I made a long show of extracting the cheap pamphlet from my briefcase, pushed it across the table, and announced, as if this were a courtroom complete with stenographers, Let the record show that this slanderous pamphlet was submitted by the defendant as evidence of Reb Shloimele’s guilt. Murder via slander, false slander, moreover, since not one of the accusations have been proven true without doubt.

I paused, looked from face to face, then continued slowly: And this court is guilty of acting as an accomplice to this murder. Even if Reb Shloimele managed to gather enough signatures to support the excommunication, and all the signatories were surely his Szebeder friends, by what right, I ask on behalf of Dobrov, did it grant the Dobrover rebbetzin a divorce and break up an entire family. Since you’re citing Jewish law, you also know that breaking up a marriage unnecessarily is equal to taking life.

The rabbi’s fist came down on the table with a thump. Enough, he said. Neither Reb Shloimele nor this court are on trial. Our sins are beside the point right now. You, however, have a lot to answer for. If you thought or knew that someone had been wronged, you ought to have come directly to us, and quietly. Instead, you took the story to the public, and not just the Jewish public. You are guilty of besmirching not only the name of a respectable man among us, but also the name of God, and worse, in front of the eyes of other nations. Retribution for befouling the name of God, as you well know, arrives directly from heaven, but this court will also do its part. You will be as a limb cut away from a body. Your wife and children will share your fate.

I took stock of the situation, decided that I was willing to take my chances with God, and since in the eyes of these men I was already judged guilty, I couldn’t make my case worse. I took a deep breath and went all the way.

Which of you here would have been willing to listen to my story? Which of you here isn’t paid, one way or another, by the Szebeder congregation. According to the law of this nation in which we live, you qualify as collaborators, and therefore ought to recuse yourself from this case. I exhaled and stood. And if, as further proof of your guilt, you require a body, here it is.

I took long strides to the door, opened it. As planned, an EMS technician wheeled into the room the Dobrover rebbe himself, frail and wraithlike, a man of fifty-three years with an early heart condition, attended by his young son in the Litvak frock.

The Dobrover appeared before us all as the Job-like figure that sooner or later every mortal becomes, but in his case the suffering had come at the hand of man rather than God, and that made all the difference.

The room remained silent for long minutes. An excommunicated man shows himself in the courtroom for only one purpose: to have the excommunication nullified, to be reborn to the community. This court had difficult days, weeks, probably, of work ahead.

I’d done my part for Dobrov. Now it remained to be seen what Dobrov would do for me. In the meantime, no one took notice when I snapped my briefcase closed loudly, adjusted the brim of my hat, and left. I had become a dead man, unseen and unheard.

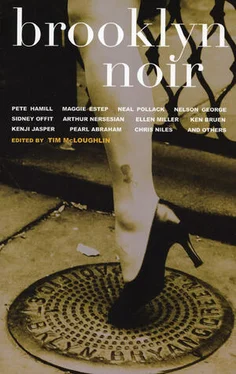

© 2004 Pearl Abraham

No time for senior’s

by Sidney Offit

Downtown Brooklyn

I’m talking murder. Murder!” she says.

It’s past noon. I’m sitting in my office near DeKalb and Flatbush, knocking off a corned-beef-lean bathed in cole slaw on seeded rye from Junior’s. And there stands Sylvia Berkowitz O’Neil, not looking her age, in high heels, short skirt, and enough makeup to drown Esther Williams and Mark Spitz on a bad day.

Before I can crack wise, Sylvia takes her first shot. “Yer eating at Junior’s? I’m working day and night, night and day, with an economy deli for the neighborhood, and you’re supporting the competition? And don’t tell me you never heard of Senior’s!”

Читать дальше