Dusty goes quietly after that.

We spring Scoop the next afternoon. Sylvia wants to celebrate with a steak at Gage and Tollner’s. She’s had enough of the deli business — “Bad memories” — and declares this her farewell party.

I.F. invites us to join him for a stroll through the Brooklyn Museum. “I’d like to take a look at Bierstadt’s Storm in the Rockies, Mt. Rosalie. A guy I met on the plane, flying in from L.A. last week, told me he’s a friend of Robert Levinson who was the chairman of the board and could recommend me for a job there. Then we can amble over to the lobby of the former Paramount Theater. It’s the Eugene & Beverly Luntey Commons of the Brooklyn Center, L.I.U. now. We could sit and read poems by Robert Donald Spector and maybe be lucky enough to run into JoAnn Allen or Mike Bush, all stars of their faculty.”

Scoop breaks into a chorus of “Thanks for the Memories” and Sylvia takes his hand like two kids on their way to the boardwalk at Coney Island.

Out of the blue, I.F. says to me, “Harold Patrick Reiser, 1941 through 1948, a Dodgers’ Dodger until he ran into a fence.” Then he gently nudges my holster. “It’s been a pleasure doing business with you, Pistol Pete.”

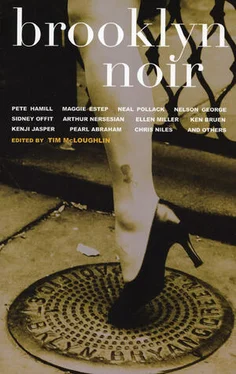

When all this was Bay Ridge

by Tim McLoughlin

Sunset Park

Standing in church at my father’s funeral, I thought about being arrested on the night of my seventeenth birthday. It had occurred in the trainyard at Avenue X, in Coney Island. Me and Pancho and a kid named Freddie were working a three-car piece, the most ambitious I’d tried to that point, and more time-consuming than was judicious to spend trespassing on city property. Two Transit cops with German shepherds caught us in the middle of the second car. I dropped my aerosol can and took off, and was perhaps two hundred feet along the beginning of the trench that becomes the IRT line to the Bronx, when I saw the hand. It was human, adult, and severed neatly, seemingly surgically, at the wrist. My first thought was that it looked bare without a watch. Then I made a whooping sound, trying to take in air, and turned and ran back toward the cops and their dogs.

At the 60th Precinct, we three were ushered into a small cell. We sat for several hours, then the door opened and I was led out. My father was waiting in the main room, in front of the counter.

The desk sergeant, middle-aged, black, and noticeably bored, looked up briefly. “Him?”

“Him,” my father echoed, sounding defeated.

“Goodnight,” the sergeant said.

My father took my arm and led me out of the precinct. As we cleared the door and stepped into the humid night he turned to me and said, “This was it. Your one free ride. It doesn’t happen again.”

“What did it cost?” I asked. My father had retired from the Police Department years earlier, and I knew this had been expensive.

He shook his head. “This once, that’s all.”

I followed him to his car. “I have two friends in there.”

“Fuck’em. Spics. That’s half your problem.”

“What’s the other half?”

“You have no common sense,” he said, his voice rising in scale as it did in volume. By the time he reached a scream he sounded like a boy going through puberty. “What do you think you’re doing out here? Crawling ’round in the dark with the niggers and the spics. Writing on trains like a hoodlum. Is this all you’ll do?”

“It’s not writing. It’s drawing. Pictures.”

“Same shit, defacing property, behaving like a punk. Where do you suppose it will lead?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t thought about it. You had your aimless time, when you got out of the service. You told me so. You bummed around for two years.”

“I always worked.”

“Part-time. Beer money. You were a roofer.”

“Beer money was all I needed.”

“Maybe it’s all I need.”

He shook his head slowly, and squinted, as though peering through the dirty windshield for an answer. “It was different. That was a long time ago. Back when all this was Bay Ridge. You could live like that then.”

When all this was Bay Ridge. He was masterful, my father. He didn’t say when it was white, when it was Irish , even the relatively tame when it was safer. No. When all this was Bay Ridge. As though it were an issue of geography. As though, somehow, the tectonic plate beneath Sunset Park had shifted, moving it physically to some other place.

I told him about seeing the hand.

“Did you tell the officers?”

“No.”

“The people you were with?”

“No.”

“Then don’t worry about it. There’s body parts all over this town. Saw enough in my day to put together a baseball team.” He drove in silence for a few minutes, then nodded his head a couple of times, as though agreeing with a point made by some voice I could not hear. “You’re going to college, you know,” he said.

That was what I remembered at the funeral. Returning from the altar rail after receiving communion, Pancho walked passed me. He’d lost a great deal of weight since I’d last seen him, and I couldn’t tell if he was sick or if it was just the drugs. His black suit hung on him in a way that emphasized his gaunt frame. He winked at me as he came around the casket in front of my pew, and flashed the mischievous smile that — when we were sixteen — got all the girls in his bed and all the guys agreeing to the stupidest and most dangerous tunts.

In my shirt pocket was a photograph of my father with a woman who was not my mother. The date on the back was five years ago. Their arms were around each other’s waists and they smiled for the photographer. When we arrived at the cemetery I took the picture out of my pocket, and looked at it for perhaps the fiftieth time since I’d first discovered it. There were no clues. The woman was young to be with my father, but not a girl. Forty, give or take a few years. I looked for any evidence in his expression that I was misreading their embrace, but even I couldn’t summon the required naïveté. My father’s countenance was not what would commonly be regarded as a poker face. He wasn’t holding her as a friend, a friend’s girl, or the prize at some retirement or bachelor party; he held her like a possession. Like he held his tools. Like he held my mother. The photo had been taken before my mother’s death. I put it back.

I’d always found his plodding predictability and meticulous planning of insignificant events maddening. For the first time that I could recall, I was experiencing curiosity about some part of my father’s life.

I walked from Greenwood Cemetery directly to Olsen’s bar, my father’s watering hole, feeling that I needed to talk to the men that nearly lived there, but not looking forward to it. Aside from my father’s wake the previous night, I hadn’t seen them in years. They were all Irish. The Irish among them were perhaps the most Irish, but the Norwegians and the Danes were Irish too, as were the older Puerto Ricans. They had developed, over time, the stereotypical hooded gaze, the squared jaws set in grim defiance of whatever waited in the sobering daylight. To a man they had that odd trait of the Gaelic heavy-hitter, that — as they attained middle age — their faces increasingly began to resemble a woman’s nipple.

The door to the bar was propped open, and the cool damp odor of stale beer washed over me before I entered. That smell has always reminded me of the Boy Scouts. Meetings were Thursday nights in the basement of Bethany Lutheran Church. When they were over, I would have to pass Olsen’s on my way home, and I usually stopped in to see my father. He would buy me a couple of glasses of beer — about all I could handle at thirteen — and leave with me after about an hour so we could walk home together.

Читать дальше