Kerry Greenwood - Tamam Shud

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kerry Greenwood - Tamam Shud» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Sydney, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: NewSouth, Жанр: Детектив, Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tamam Shud

- Автор:

- Издательство:NewSouth

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:Sydney

- ISBN:978-1-742-23350-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tamam Shud: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tamam Shud»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Tamam Shud — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tamam Shud», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Over the grave a headstone was erected, which says, ‘Here lies the unknown man who was found at Somerton beach 1st Dec 1948’. Thereafter, a woman was observed putting a red rose on his grave every year on 1 December. Police interviewed the woman and reported that she had no connection to the case but, frustratingly, they do not give her name. Later, observers noticed that pebbles had been piled on the grave, which is a way of marking a Jewish resting place, but Somerton Man was uncircumcised and therefore very unlikely to be a Jew. Though it is possible. Some Jewish children, trapped in Germany and sent to Christian institutions by prescient parents, remained uncircumcised to escape annihilation. But Somerton Man, who must have been born around the turn of that century, was too old for this to have been his fate.

Years passed without much more than a series of by now predictable headlines declaring that the body of Somerton Man had been identified, followed next day by the news that he had not. Lost luggage was inspected without result and missing persons were either found or continued missing. Nothing. Finally, on 14 March 1958, the long-suffering Coroner, Thomas Cleland, came to the reluctant conclusion that he had to close his inquiry, saying, ‘I, the said Justice of the Peace and the Coroner, do say that I am unable to say who the deceased was. He died on the shore at Somerton on the 1 stof December 1948. I am unable to say how he died or what was the cause of death’. And that, for the legal system, was that.

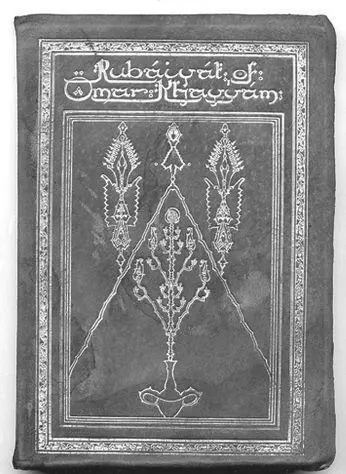

Subsequently, the autopsy reports, the suitcase, and The Rubaiyat were thrown out in successive police springcleanings. Other writers have waxed indignant about this but I perfectly understand. The police evidence lockers are always bulging with stuff, so when a case is stonecold, that is what has to happen to the evidence. Besides, supposing we still had the actual socks that Somerton Man wore, would it help us at all? Even if we had samples of his DNA, to whom would we compare it? I have to admit I do wish that the actual autopsies had survived but want, as Grandma used to say, must be my master.

Just after the Coroner called it quits, a New Zealand prisoner named EB Collins announced that he knew Somerton Man. The story appeared in the Sunday Mirror , which was published in Sydney. Gerald Feltus, who has access to the police reports, states that the New Zealand police interviewed Mr Collins, who declined to impart any more information, stating that he was going to be paid a lot of money for his story by a newspaper. However, no story subsequently appeared.

Information volunteered by prisoners is always suspect but it does show that the Somerton Beach mystery still interested the media. The interest has never gone away. The media have had a lovely time with Somerton Man. My researcher collected over a hundred newspaper clippings from the invaluable Trove on the internet, each of them reporting a new solution to the mystery, all of which somehow proved not to be conclusive.

Then there are the coincidences. Fictional detectives are fond of making pronouncements like ‘There are no coincidences’, and they are right in two senses – firstly, in the sense that no coincidences can happen in an intricate, infinitely complex world system in which butterflies flapping their wings create tornados, and secondly in the sense that no coincidences are allowed in fiction. Fictional investigations have much stricter rules than investigations in real life. In the Golden Age of detective stories, the most important rule was that the murder should never turn out to have been committed by a wandering axe murder whom no one had previously noticed. This is not because there are no wandering axe murderers in the world; sadly, there are. It is because readers of crime fiction rightly demand three things – a crime, a detective and a solution. Crime fiction is a puzzle and the author must play fair and give the reader all the facts they need to solve the mystery. Coincidences happen all the time in real life but if they happen in crime fiction, the reader feels cheated. Usually, however, an editor will return a coincidence-ridden manuscript and sternly instruct the author to rewrite it, so the reader never gets to see it.

Coincidences happen in court on many occasions. My favourite was the little ratbag who, after spending his youth with a collection of like-minded friends stealing cars and causing trouble, had been sentenced to a youth training facility but had escaped. He ran away to South Australia, got a job and a bank account, got married, had children and took them back ten years later to visit his old mum in Melbourne, counting, quite reasonably, on the fact that he had changed a great deal and that no one was actively looking for him. Then he stepped out on a crossing and was run over by a car and the police officer who picked him up off the road was – you guessed it – the one who had originally put him away. Apparently, the cop said ‘Hi, Jimmy’, and Jimmy said ‘Hi, Sarge’. When the case came to court, I argued that the Children’s Court sentence was meant to reform and keep him out of trouble, which it appeared to have done, so could we call it quits? And we did.

There have also been some remarkable coincidences in my own writing career, notably the day when my Muse suggested South China Sea pirates for a novel I was already writing. I was at court at the time and rather busy. ‘Nonsense,’ I told her. ‘I am already writing this book. I can’t knock off for a month’s research.’ But she persisted, so I said, ‘All right, Muse, I have to pass Sunshine Library on the way home. If I put my hand on a book about South China Sea pirates in the early twentieth century, I’ll do it. If not, not,’ which at least stopped her nagging. On the way home I ducked into Sunshine Library and there in the middle of the returns tray, right in front of my eyes and right under my hand, was The Black Flag: A History of Piracy in the South China Seas in the Early 20th Century by James Hepburn. I borrowed the book and put the pirates into the plot because ignoring something like that could cause my Muse to get huffy and I would hate to offend her.

Whole philosophical theories have been based on coincidence or synchronicity. Think of Jung. Think of Koestler. The world is not ruled by straight logic or exact causality. Not all of the things that look as if they might be connected are connected. Not all of the things that happen at the same time or in the same way have the same cause. Take, for example, the cases that are often cited as being similar in some sense to the enigmatic death of Somerton Man.

The first is the case of Clive Mangnoson, a two-yearold child, who, in June 1949, was found dead in a sack on the beach at Largs Bay, which is about 20 kilometres down the coast from Somerton Beach. Lying next to the child was his father Keith, suffering from exposure. The two of them had been missing for four days. The child had died of unknown causes and the man was unable to give an account of what had happened. They were found by a man who said he had been led to them by a dream. Mr Mangnoson’s wife said that the family had been terrorised by a man wearing a khaki handkerchief over his face, who, after almost running her down, told her to ‘keep away from the police or else’. Mrs Mangnoson subsequently had a perfectly understandable nervous breakdown.

The connection between the Mangnoson case and the case of Somerton Man is that Keith Mangnoson was one of the people who thought he knew Somerton Man’s identity. He had gone to the police and told them that Somerton Man was one Carl Thompsen, whom he had met in Renmark in 1939. So was young Clive Mangnoson killed by unknown means in order to force his father to withdraw his identification? In which case, why did the killer or killers leave Keith alive? Wouldn’t it have been easier to kill the father and allow the child to live? And why go about it in a way that inevitably attracted attention, in the same way as Somerton Man had attracted attention?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tamam Shud»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tamam Shud» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tamam Shud» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.