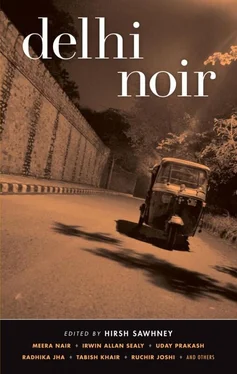

Omair Ahmad - Delhi Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Omair Ahmad - Delhi Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Delhi Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-933354-78-1

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Delhi Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Delhi Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Brand-new stories by

Delhi Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Delhi Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The flames rose high. It struck me suddenly that the dead man and I were similar. We had both been robbed of our clothes while we were defenseless and dreaming. I wondered what would happen if the man came alive after the crowds had left and found his body half-burnt and naked. Would he lie back down and ask for more wood and oil, or would he demand some clothes? I knew what I would do. I would demand clothes and go a.s.a.p. to find my son.

But the man didn’t move a muscle. The smoke thickened and grew bitter and people began to drift away. The pundits finished their work and the family moved to the entrance to say goodbye to the guests. Soon there was only an attendant left, a grizzled old man with coal-black skin who was no doubt paid by the family to make sure the body burnt till the end. Bones, I vaguely remembered, took a long time and a lot of oil and wood. The body would take four or five hours, and then the family would return for a box of ashes that they’d carry to the polluted Yamuna, where they would pay more money for more prayers.

Up in the tree, I shifted uncomfortably, the bark rough against my skin, the mango leaves filled with dust and diesel exhaust, praying that the old watchman would leave to take a pee or have a smoke. But to my surprise, he didn’t. He remained where he was, morosely watching the pyre, the white hairs on his beard and head getting picked out by the flames.

The fire burnt well. The ghee, it seemed, had not been adulterated. I heard the bones crack and a new, truly awful smell filled the air. I began to cough and the old man looked up in surprise. But the leaves of the tree must have been dense and plentiful or his eyes were weak, because he didn’t spot me. I decided to abandon my post and rescue my sheet straight away. What if there were secret caches of oil in the wood that were even now destroying it?

I got down on the ground and armed myself with a piece of wood from the pyre. Then I crept around the old man and hit him on the back of his head. He turned just as I swung, perhaps his hearing was especially sharp or else it was pure coincidence, and the branch smashed into his face, breaking his nose. He let out a cry and then fell slowly, like in a movie. I dropped the branch and dashed around to the other side of the pyre, scrambling up the unburnt logs even though the heat was something terrible.

Through the smoke and my tears I saw the edge of a sheet gleaming whitely just above my left hand. One more foothold, and I had the sheet grasped firmly and pulled.

I hadn’t thought it out at all though. I could have saved myself the trouble by simply stealing the clothes of the unconscious guard. Instead I burnt my hands and feet and almost got myself killed. When I used a burning branch to free the sheet, the body came along with it. We both tumbled to the ground, the body’s half-burnt face on top of me. I don’t know how but his eyes were open and staring into mine expressionlessly.

I threw the body off me — it was unbelievably heavy — and grabbed the sheet on which it had lain. The sheet still smelled sweet like rose water, and I wrapped it around my waist like a lungi, taking care to conceal the burnt bits. Then I ran, I ran as fast as I could out of that place of death.

I made it to the Lodhi Hotel compound on the other side of the road. Of course, there was no Lodhi Hotel left. It had been bought and torn down, Russian kitsch to be replaced by modern kitsch. Back in the old days the hotel had belonged to the government and was filled with pretty Russian hookers. I had liked it then — the idea of a government building filled with hookers always managed to stir my desire. Now it was a construction site.

At first no one bothered me. I wandered amongst the screens and piles of rubble, drinking in the sweet music of many chisels hitting stone. Then I heard a voice behind me. “Hey, what do you want? This is private property,” it barked. I ignored the bark. That’s what you do, ignore dogs that bark. I had a lot of experience with dogs.

The music of the chisels stopped. Everyone was looking at me.

“This is no dharamshala, this is a hotel. You will get no money or food here. Get going!” the guard shouted, banging his stick. I noticed that his uniform was black and red and he looked out of place in that world of sandstone and cool white marble.

“ You get going,” I said calmly, “ you don’t belong here.”

The man raised his stick and would have struck me but I was saved by the appearance of a pretty blond creature in a kurta and hippie skirt. “Stop, stop!” she called.

The guard immediately became deferential.

“What does this man want?” the woman asked.

“I don’t know, madam,” he replied dubiously. “But don’t worry, I’ll chase him away. He’s probably a thief.”

“I am no thief.” I said scornfully, “I was just looking.”

She turned to me, and to my surprise she actually looked at my body and my face. And I felt them respond to her.

“Work, I want work,” I said in English.

She seemed taken aback. Her eyes narrowed in suspicion. She was no fool. She had seen the junkies in the park by the Nizamuddin Bridge underpass. She looked at my lungi. “But you have no clothes,” she muttered.

“They were stolen,” I replied.

She peered at me sharply, suspicion hardening into conviction. “Then go get some,” she said coldly, “and we’ll consider you.” The wall that all white women had inside them had gone up. It felt harder than stone.

The guard wasn’t following any of this, but he understood, like all good guard dogs did, her change of tone. Grabbing me by the shoulder, he hustled me out. At the gate, maybe because he had a sense of humor or else because he was genuinely sorry for me, he picked up a sheet of pink plastic and handed it to me. “Here, you can make this into a shirt,” he said.

I clutched the plastic to my chest, tears blurring my vision. Once outside, I found I was right by ground zero, the place it had all begun. But this time I decided not to go back into the park. Instead I walked along Lodhi Road, past the church, past HUDCO where Sharmila sat each day on the twelfth floor, giving misguided middle-class couples extremely expensive housing loans, past the gas pump that sold Norwegian smoked salmon and pork chops, past the Islamic cultural center and the Ramakrishna Mission, past Tibet House and the Habitat Center — all the landmarks of Delhi’s cultural life.

I came at last to Lodhi Gardens. The sun was almost gone but inside the gardens the privileged continued their leisurely parade — ayahs with children, bored overweight mothers, joggers, sedate couples, bureaucrats, cell phone — wielding politicians, upwardly mobile businessmen. No one gave me a second glance as I slipped into the garden. They were all too interested in watching each other. The ministers and bureaucrats pretended not to see anyone. The others watched the ministers and bureaucrats. I walked amongst them till I came to a hexagonal tomb encircled by palm trees and slipped inside. There I would wait for darkness to fall, thinking about my old life and what a sad mess I’d made of it. Footsteps interrupted my thoughts. Voices, giggles.

I looked around desperately for somewhere to hide

The only place I could see was between the two tombstones in the middle of the room. I had barely squeezed myself in there when the lovers arrived. She had a terrible shrill sort of giggle which was nasal and unmusical. His voice was okay.

“Ao na,” he was saying.

Giggle, giggle. “Na, na.”

“Ao na.”

“Na, na.”

“What are you scared of? Do you think your mother will jump out from behind a pillar?”

Giggle, giggle again. “Na, na darling. I was just—” She stopped.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Delhi Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Delhi Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Delhi Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.