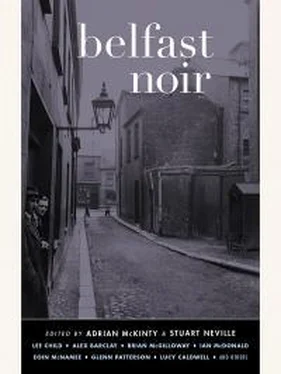

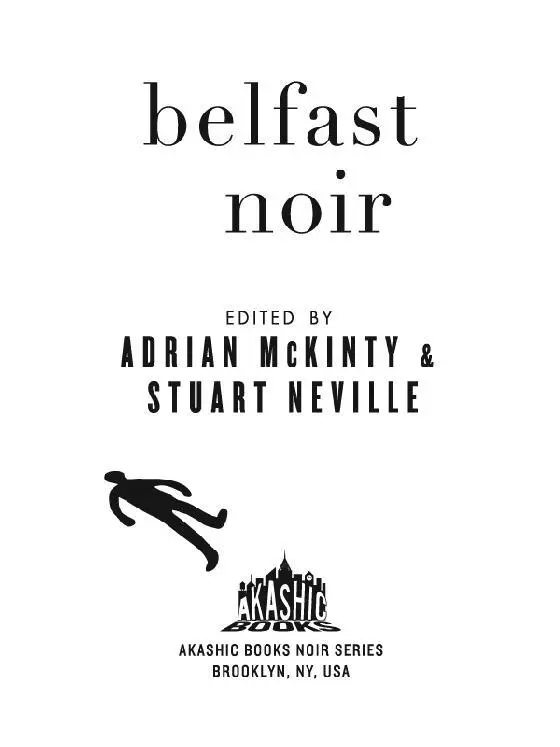

Table of Contents

___________________

Introduction by Adrian McKinty & Stuart Neville

Foreword by David Torrans

PART I: CITY OF GHOSTS

The Undertaking

BRYAN MCGILLOWAY

Roselawn

Poison

LUCY CALDWELL

Dundonald

Wet with Rain

LEE CHILD

Great Victoria Street

Taking It Serious

RUTH DUDLEY EDWARDS

Falls Road

PART II: CITY OF WALLS

Ligature

GERARD BRENNAN

Hydebank

Belfast Punk REP

GLENN PATTERSON

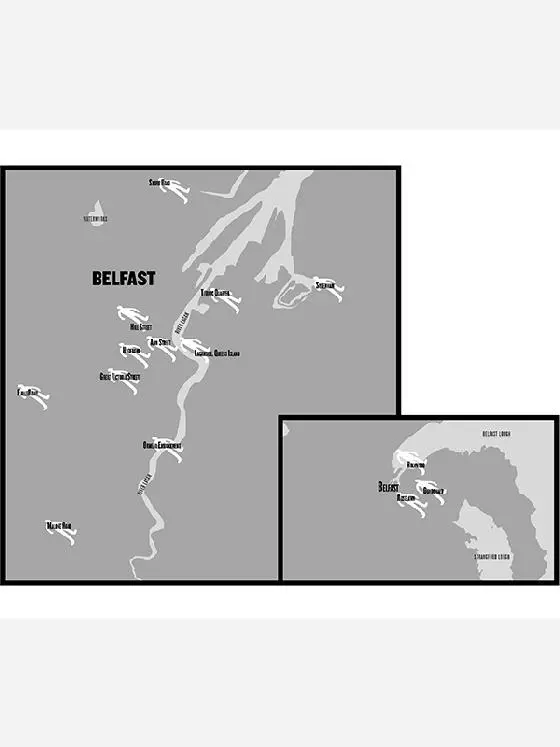

Ann Street

The Reservoir

IAN MCDONALD

Holywood

PART III: CITY OF COMMERCE

The Grey

STEVE CAVANAGH

Laganside, Queens Island

Rosie Grant's Finger

CLAIRE MCGOWAN

Titanic Quarter

Out of Time

SAM MILLAR

Hill Street

Die Like a Rat

GARBHAN DOWNEY

Malone Road

PART IV: BRAVE NEW CITY

Corpse Flowers

EOIN MCNAMEE

Ormeau Embankment

Pure Game

ARLENE HUNT

Sydenham

The Reveller

ALEX BARCLAY

Shore Road

About the Contributors

Sneak Peek: USA NOIR

Also in Akashic Noir Series

Akashic Noir Series Awards & Recognition

About Akashic Books

Copyrights & Credits

INTRODUCTION

THE NOIREST CITY ON EARTH

Few European cities have had as disturbed and violent a history as Belfast over the last half-century. For much of that time the Troubles (1968–1998) dominated life in Ireland’s second-biggest population centre, and during the darkest days of the conflict—in the 1970s and 1980s—riots, bombings, and indiscriminate shootings were tragically commonplace. The British army patrolled the streets in armoured vehicles and civilians were searched for guns and explosives before they were allowed entry into the shopping district of the city centre.

A peace process that began in 1998 with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement has brought a measure of calm to Belfast, but during the summer “Marching Season” rioting between Catholic and Protestant working-class districts often flares up to this day.

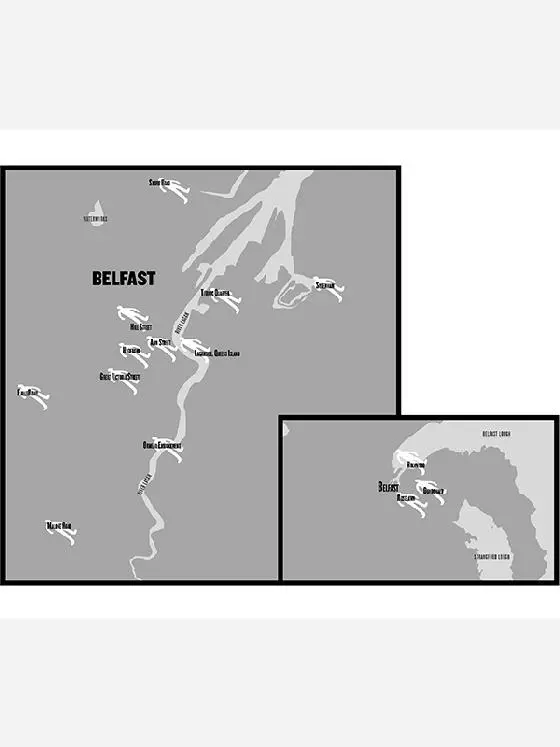

Belfast is still a city divided. East Belfast is a largely Protestant working-class district. South Belfast is a prosperous middle-class enclave centred around Queens University. West and North Belfast, where Catholic and Protestant working-class districts jut up against one another is the area of greatest conflict and where the fracture lines are at their most raw. So-called “peace walls” have been built to separate adjacent streets of Protestant and Catholic families, with more having been added since the peace agreement of ’98.

The north of Ireland has always been a slightly different place than the south. For centuries Ulstermen and -women have been blessed with a unique accent, a mordant sense of humour, and a taciturnity unshared by most of their countrymen in the rest of the island. Attempts have been made to explain the province of Ulster’s singularity by laying the blame at the door of thousands of dour Scottish planters who began arriving in the northeast of Ireland in the early 1600s. Of course the Ulster plantation changed the religious complexion of the north, but well before then “the land beyond the Mournes” revelled in its exceptionalism. Ulster was the most Gaelic and least English province of Ireland in the early seventeenth century, and further back into the mists of prehistory the story of the Táin Bó Cúailnge was that of Cuchulain, champion of Ulster, battling the forces of Erin.

Belfast was little more than a village for much of this time. The name probably derives from the Irish, béal feirste , which means river-mouth, and for centuries it was an uninteresting settlement on the mudflats where the River Lagan joined Belfast Lough.

In the nineteenth century shipbuilding, heavy engineering, and linen manufacture led to Belfast’s exponential growth, and by 1914 a tenth of all the ships and a third of all the linen clothes made in the British Empire were coming from the city. Belfast was Ireland’s boom town and Dublin the mere administrative capital.

But World War I, the 1916 Easter Rising, and the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) led to the creation of a border that separated the six counties of Northern Ireland from the twenty-six counties of the Irish Free State. Post-partition Northern Ireland suffered from an inferiority complex. Cut off from cultural developments in Dublin and London, Belfast became something of a provincial backwater. Belfast was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe in World War II and postwar reconstruction was piecemeal at best.

International literary trends tended to pass Ulster by, and Northern Irish fiction itself went through a lean period until well after the end of World War II. A rare cultural highlight was F.L. Green’s Odd Man Out , which led to Carol Reed’s extraordinary film noir adaptation starring James Mason.

But the decline of engineering, shipbuilding, and linen manufacture had a devastating impact on Belfast and it was a gloomy, depressed, unfashionable Victorian city that encountered the years of conflict and low-level civil war known euphemistically as the Troubles.

What began as a series of peaceful marches for civil rights for Northern Ireland’s Catholic minority in the late ’60s quickly morphed into street violence and random sectarian attacks. As the crisis in the north intensified, the British government deployed the army and suspended Northern Ireland’s parliament. Direct rule from London did not allay the fears of the Catholic minority and the Provisional Irish Republican Army began to recruit volunteers for their campaign to violently overthrow the British. In reaction to the IRA bombings and shootings, successive British governments panicked: interring IRA suspects without trial, flooding Northern Ireland with yet more soldiers, and strengthening the local police—the Royal Ulster Constabulary. And of course violence spiralled into more violence. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) reformed to counter the Provisional IRA, and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) became an umbrella group for various Protestant factions. Of course the majority of those killed were innocent civilians on both sides.

A depressing three decade–long cycle of atrocities and massacres had begun.

By this time much of Northern Ireland’s writing talent—intellectuals such as Brian Moore, C.S. Lewis, and Louis MacNeice—had left the province to ply their trade under brighter lights, and Belfast languished culturally until the early 1970s when in the midst of the Troubles the city became the focus of an extraordinary group of poets who went on to attain world renown: Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon, Derek Mahon, Ciaran Carson, Michael Longley, Tom Paulin, among others. Based loosely around Queens University, these young poets produced the greatest body of Irish literary work since the Gaelic revival. As the violence worsened, ironically, Belfast grew in cultural confidence, kick-started by this incendiary poetry, which in turn provided the kerosene for the other arts. By the late-1970s Northern Ireland saw a boom in playwriting, screenwriting, songwriting, and finally in novel writing.

Bernard MacLaverty’s Cal (1983) was one of the first and best crime novels to address the complexities of life during the Troubles, and the Belfast-set Lies of Silence (1990) by Brian Moore established the city as a labyrinth of twisting allegiances and blind alleys. Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man (1994) is a portrait of Belfast as a city of the abyss in which sociopathic Protestant serial killers stalk the streets looking for random Catholic victims. Resurrection Man was based on the true story of the Shankill Butchers.

Читать дальше