‘Good evening, Colonel Kramer.’

‘Evening, Captain. Evening, Fräulein.’ He had an unexpectedly gentle and courteous voice. ‘You wear an air of expectancy?’

Before either could answer, the door opened and Anne-Marie and Mary entered: Mary gave the impression of having been pushed into the room. Anne-Marie was slightly flushed and breathing rather heavily, but otherwise her beautiful Aryan self. Mary’s clothes were disordered, her hair dishevelled and it was obvious that she had been crying. Her cheeks were still tear-stained.

‘We’ll have no more trouble with her ,’ Anne-Marie announced with satisfaction. She caught sight of Kramer and the change in her tone was perceptible. ‘Interviewing new staff, Colonel.’

‘In your usual competent fashion, I see,’ Colonel Kramer said dryly. He shook his head. ‘When will you learn that respectable young girls do not like being forcibly searched and having their under-clothes examined to see if they were made in Piccadilly or Gorki Street?’

‘Security regulations,’ Anne-Marie said defensively.

‘Yes, yes.’ Kramer’s voice was brusque. ‘But there are other ways.’ He turned away impatiently. The engaging of female staff was not the problem of the deputy chief of the German Secret Service. While Heidi was helping Mary to straighten her clothes, he went on, to von Brauchitsch: ‘A little excitement in the village tonight?’

‘Nothing for us.’ Von Brauchitsch shrugged. ‘Deserters.’

Kramer smiled.

‘That’s what I told Colonel Weissner to say. I think our friends are British agents.’

‘What!’

‘After General Carnaby, I shouldn’t wonder,’ Kramer said carelessly. ‘Relax, Captain. It’s over. Three of them are coming up for interrogation within the hour. I’d like you to be present later on. I think you’ll find it most entertaining and – ah– instructive.’

‘There were five of them, sir. I saw them myself when they were rounded up in “Zum Wilden Hirsch”.’

‘There were five,’ Colonel Kramer corrected. ‘Not now. Two of them – the leader and one other – are in the Blau See. They commandeered a car and went over a cliff.’

Mary, her back to the men and Anne-Marie, smoothed down her dress and slowly straightened. Her face was stricken. Anne-Marie turned, saw Mary’s curiously immobile position and was moving curiously towards her when Heidi took Mary’s arm and said quickly: ‘My cousin looks ill. May I take her to her room?’

‘All right.’ Anne-Marie waved her hand in curt dismissal. ‘The one you use when you are here.’

The room was bleak, monastic, linoleum-covered, with a made-up iron bed, chair, tiny dressing-table, a hanging cupboard and nothing else. Heidi locked the door behind them.

‘You heard?’ Mary said emptily. Her face was as drained of life as her voice.

‘I heard – and I don’t believe it.’

‘Why should they lie?’

‘ They believe it.’ Heidi’s tone was impatient, almost rough. ‘It’s time you stopped loving and started thinking. The Major Smiths of this world don’t drive over cliff edges.’

‘Talk is easy, Heidi.’

‘So is giving up. I believe he is alive. And if he is, and if he comes here and you’re gone or not there to help him, you know what he’ll be then?’ Mary made no reply, just gazed emptily into Heidi’s face. ‘He’ll be dead. He’ll be dead because you let him down. Would he let you down?’

Mary shook her head dumbly.

‘Now then,’ Heidi went on briskly. She reached first under her skirt then down the front of her blouse and laid seven objects on the table. ‘Here we are. Lilliput .21 automatic, two spare magazines, ball of string, lead weight, plan of the castle and the instructions.’ She crossed to a corner of the room, raised a loose floor-board, placed the articles beneath it and replaced the board. ‘They’ll be safe enough there.’

Mary looked at her for a long moment and showed her first spark of interest in an hour.

‘You knew that board was loose,’ she said slowly.

‘Of course. I loosened it myself, a fortnight ago.’

‘You – you knew about this as far back as then?’

‘Whatever else?’ Heidi smiled. ‘Good luck, cousin.’

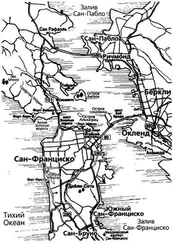

Mary sank on to the bed and sat there motionless for ten minutes after Heidi had gone, then rose wearily to her feet and crossed to her window. Her window faced to the north and she could see the line of pylons, the lights of the village and, beyond that, the darkened waters of the Blau See. But what dominated the entire scene were the redly-towering flames and billowing clouds of black smoke reaching up from some burning building at the far end of the village. For a hundred yards around it night had been turned into day and even if there had been a local fire brigade to hand it would have been clearly impossible for them to approach anywhere near the flames. When that fire went out all that would be left would be smoking ashes. Mary wondered vaguely what it might mean.

She opened her window and leaned out, but cautiously. Even for a person as depressed as she was, there was no temptation to lean too far: castle walls and volcanic plug stretched vertically downwards for almost three hundred feet. She felt slightly dizzy.

To the left and below a cable-car left the castle header station and started to move down to the valley below. Heidi was in that car, leaning out a partially opened window and hopefully waving but Mary’s eyes had again blurred with tears and she did not see her. She closed the window, turned away, lay down heavily on the bed and wondered again about John Smith, whether he were alive or dead. And she wondered again about the significance of that fire in the valley below.

Smith and Schaffer skirted the backs of the houses, shops and Weinstuben on the east side of the street, keeping to the dark shadows as far as it was possible. Their precautions, Smith realized, were largely superfluous: the undoubted centre of attraction that night was the blazing station and the street leading to it was jammed with hundreds of soldiers and villagers. It must, Smith thought, be a conflagration of quite some note, for although they could no longer see the fire itself, only the red glow in the sky above it, they could clearly hear the roaring crackle of the flames, flames three hundred yards away and with the wind blowing in the wrong direction. As a diversion, it was a roaring success.

They came to one of the few stone buildings in the village, a large barn-like affair with double doors at the back. The yard abutting the rear doors looked like an automobile scrapyard. There were half-a-dozen old cars lying around, most of them without tyres, some rusted engines, dozens of small useless engine and body parts and a small mountain of empty oil drums. They picked their way carefully through the debris and came to the doors.

Schaffer used skeleton keys to effect and they were inside, doors closed and both torches on, inside fifteen seconds.

One side of the garage was given over to lathes or machine tools of one kind or another, but the rest of the floor space was occupied by a variety of vehicles, mostly elderly. What caught and held Smith’s immediate attention, however, was a big yellow bus parked just inside the double front doors. It was a typically Alpine post-bus, with a very long overhang at the back to help negotiate mountain hairpin bends: the rear wheels were so far forward as to be almost in the middle of the bus. As was also common with Alpine post-buses in winter, it had a huge angled snow-plough bolted on to the front of the chassis. Smith looked at Schaffer.

‘Promising, you think?’

‘If I was optimistic enough to think we’d ever get back to this place,’ Schaffer said sourly, ‘I’d say it was very promising. You knew about this?’

Читать дальше