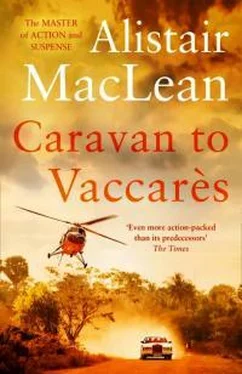

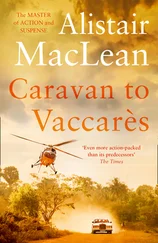

Alistair MacLean

CARAVAN TO VACCARÈS

1970

Alistair MacLean, the son of a Scots minister, was born in 1922 and brought up in the Scottish Highlands. In 1941 at the age of eighteen he joined the Royal Navy; two-and-a-half years spent aboard a cruiser was later to give him the background for HMS Ulysses , his first novel, the outstanding documentary novel on the war at sea. After the war, he gained an English Honours degree at Glasgow University, and became a school master. In 1983 he was awarded a D.Litt from the same university.

By the early 1970s he was one of the top 10 bestselling authors in the world, and the biggest-selling Briton. He wrote twenty-nine worldwide bestsellers that have sold more than 30 million copies, and many of which have been filmed, including The Guns of Navarone, Where Eagles Dare, Fear is the Key and Ice Station Zebra . He is now recognized as one of the outstanding popular writers of the 20th century. Alistair MacLean died in 1987 at his home in Switzerland.

To Jean-André and Emanuela Charial

They had come a long way, those gypsies encamped for their evening meal on the dusty greensward by the winding mountain road in Provence. From Transylvania they had come, from the pustas of Hungary, from the High Tatra of Czechoslovakia, from the Iron Gate, even from as far away as the gleaming Rumanian beaches washed by the waters of the Black Sea. A long journey, hot and stifling and endlessly, monotonously repetitive across the already baking plains of Central Europe or slow and difficult and exasperating and occasionally dangerous in the traversing of the great ranges of mountains that had lain in their way. Above all, one would have thought, even for those nomadic travellers par excellence, a tiring journey.

No traces of any such tiredness could be seen in the faces of the gypsies, men, women and children all dressed in their traditional finery, who sat or squatted in a rough semi-circle round two glowing coke braziers, listening in quietly absorbed melancholy to the hauntingly soft and nostalgic tsigane music of the Hungarian steppes. For this apparent lack of any trace of exhaustion there could have been a number of reasons: as the very large, modern, immaculately finished and luxuriously equipped caravans indicated, the gypsies of today travel in a degree of comfort unknown to their forebears who roamed Europe in the horse-drawn, garishly-painted and fiendishly uncomfortable covered-wagon caravans of yesteryear: they were looking forward that night to the certainty of replenishing coffers sadly depleted by their long haul across Europe – in anticipation of this they had already changed from their customary drab travelling clothes: only three days remained until the end of their pilgrimage, for pilgrimage this was: or perhaps they just had remarkable powers of recuperation. Whatever the reason, their faces reflected no signs of weariness, only gentle pleasure and bitter-sweet memories of faraway homes and days gone by.

But one man there was among them whose expression – or lack of it – would have indicated to even the most obtusely unobservant that, for the moment at least, his lack of musical appreciation was total and his thoughts and intentions strictly confined to the present. His name was Czerda and he was sitting on the top of the steps of his caravan, apart from and behind the others, a halfseen shadow on the edge of darkness. Leader of the gypsies and hailing from some unpronounceable village in the delta of the Danube, Czerda was of middle years, lean, tall and powerfully built, with about him that curiously relaxed but instantly identifiable stillness of one who can immediately transform apparent inertia into explosive action. He was dressed all in black and had black hair, black eyes, black moustache and the face of a hawk. One hand, resting limply on his knee, held a long thin smouldering black cigar, the smoke wisping up into his eyes, but Czerda did not seem to notice or care.

His eyes were never still. Occasionally he glanced at his fellow-gypsies, but only briefly, casually, dismissively. Now and again he looked at the range of the Alpilles, their gaunt forbidding limestone crags sleeping palely in the brilliant moonlight under a star-dusted sky, but for the most part he glanced alternately left and right along the line of parked caravans. Then his eyes stopped roving, although no expression came to replace the habitual stillness of that face. Without haste he rose, descended the steps, ground his cigar into the earth and walked soundlessly to the end of the row of caravans.

The man who stood waiting in the shadows was a youthful, scaled-down replica of Czerda himself. Not quite so broad, not quite so tall, his swarthily aquiline features were cast in a mould so unmistakably similar to that of the older man that it was unthinkable that he could be anything other than his son. Czerda, clearly a man not much given to superfluous motion or speech, raised a questioning eyebrow: his son nodded, led him out on to the dusty roadway, pointed and made a downward slicing, chopping motion with his hand.

From where they stood and less than fifty yards away soared an almost vertical outcrop of white limestone rock, but an outcrop which has no parallel anywhere in the world, for its base was honeycombed with enormous rectangular entrances, cut by the hand of man – no feat of nature could possibly have reproduced the sharply geometrical linearity of those apertures in the cliff face: one of those entrances was quite huge, being at least forty feet in height and no less in width.

Czerda nodded, just once, turned and looked down the road to his right. A vague shape detached itself from shadow and lifted an arm.

Czerda returned the salute and pointed towards the limestone bluff. There was no acknowledgment and clearly none was necessary, for the man at once disappeared, apparently into the rock face. Czerda turned to his left, located yet another man in the shadows, made a similar gesture, accepted a torch handed him by his son and began to walk quickly and quietly towards the giant entrance in the cliff face. As they went, moonlight glinted on the knives both men held in their hands, very slender knives, long-bladed and curved slightly at the ends. As they passed through the entrance of the cave they could still distinctly hear the violinists change both mood and tempo and break into the lilting cadences of a gypsy dance.

Just beyond the entrance the interior widened out and heightened until it was like the inside of a great cathedral or a giant tomb of antiquity. Both Czerda and his son switched on their torches, the powerful beams of which failed to penetrate the farthest reaches of this awesome man-made cave, and man-made it unquestionably was, for clearly visible on the towering side-walls were the thousands of vertical and horizontal scores where long-dead generations of Provençals had sawn away huge blocks of the limestone for building purposes.

The floor of this entrance cavern – for, vast though it was, it was no more than that – was pitted with rectangular holes, some of them large enough to hold a motor car, others wide and deep enough to bury a house. Scattered in a few odd corners were mounds of rounded limestone rock but, for the most part, the floor looked as if it had been swept only that day. To the right and left of the entrance cavern led off two other huge openings, the darkness lying beyond them total, impenetrable. A doom-laden place, implacable in its hostility, foreboding, menacing, redolent of death. But Czerda and his son seemed unaware of any of this, quite unmoved: they turned and walked confidently towards the entrance to the right-hand chamber.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу