Harry Turtledove - Krispos Rising

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Harry Turtledove - Krispos Rising» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Книги. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

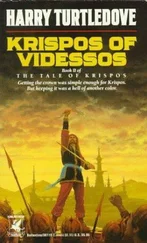

- Название:Krispos Rising

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Krispos Rising: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Krispos Rising»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Krispos Rising — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Krispos Rising», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He woke up on the cold stone floor.

Trembling, Pyrrhos got to his feet. He was a bold man; even now, he started to return to his bed. But when he thought of the enthroned judge and those terrible eyes—and how they would look should he disobey yet again—boldness failed. He opened the door to his chamber and stepped out into the hallway.

Two monks returning to their cells from a late-night prayer vigil glanced up in surprise to see someone approaching them. As was his right, Pyrrhos stared through them as if they did not exist. They bowed their heads and, without a word, stood aside to let the abbot pass.

The door to the common room was barred on the side away from the men the monastery took in. Pyrrhos had second thoughts as he lifted the bar—but he had not fallen out of bed since he was a boy. He could not make himself believe he had fallen out of bed tonight. Shaking his head, he went into the common room.

As always, the smell hit him first, the smell of the poor, the hungry, the desperate, and the derelict of Videssos: unwashed humanity, stale wine, from somewhere the sharp tang of vomit. Tonight the rain added damp straw's mustiness and the oily lanolin reek of wet wool to the mix.

A man said something to himself as he turned over in his sleep. Others snored. One fellow sat against a wall, coughing the consumptive's endless racking bark. I'm to pick one of these men to treat as my son? the abbot thought. One of these?

It was either that or go back to bed. Pyrrhos got as far as putting his fingers on the door handle. He found he did not dare to work it. Sighing, he turned back. "Krispos?" he called softly.

A couple of men stirred. The consumptive's eyes, huge in his thin face, met the abbot's. He could not read the expression in them. No one answered him.

"Krispos?" he called again.

This time he spoke louder. Someone grumbled. Someone else sat up. Again, no one replied. Pyrrhos felt the heat of embarrassment rise to the top of his tonsured head. If nothing came of this night's folly, he would have some explaining to do, perhaps even—he shuddered at the thought—to the patriarch himself. He hated the idea of making himself vulnerable to Gnatios' mockery; the ecumenical patriarch of Videssos was far too secular to suit him. But Gnatios was Petronas' cousin, and so long as Petronas was the most powerful man in the Empire, his cousin would remain at the head of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

One more fruitless call, the abbot thought, and his ordeal would be over. If Gnatios wanted to mock him for it, well, he had endured worse things in his service to Phos. That reflection steadied him, so his voice rang out loud and clear: "Krispos?"

Several men sat up now. A couple of them glared at Pyrrhos for interrupting their rest. He had already begun to turn to go back to his chamber when someone said, "Aye, holy sir, I'm Krispos. What do you want of me?"

It was a good question. The abbot would have been happier with a good answer for it.

Krispos sat in the monastery study while Pyrrhos bustled about lighting lamps. When that small, homely task was done, the abbot took a chair opposite him. The lamplight failed to fill his eyesockets or the hollows of his cheeks, leaving his face strange and not quite human as he studied Krispos.

"What am I to do with you, young man?" he said at last.

Krispos shook his head in bewilderment. "I couldn't begin to tell you, holy sir. You called, so I answered; that's all I know about it." He fought down a yawn. He would sooner have been back in the common room, asleep.

"Is it? Is it indeed?" The abbot leaned forward, voice tight with suppressed eagerness. It was as if he were trying to find out something from Krispos without letting on that he was trying to.

By that sign, Krispos knew him. He had been just so a dozen years before, asking questions about the goldpiece Omurtag had given Krispos—the same goldpiece, he realized, that he had in his pouch. Save for the passage of time, which sat lightly on it, Pyrrhos' gaunt, intent face was also the same.

"You were up on the platform with Iakovitzes and me," Krispos said.

The abbot frowned. "I crave pardon? What was that?"

"In Kubrat, when he ransomed us from the wild men," Krispos explained.

"I was?" Pyrrhos' gaze suddenly sharpened; Krispos saw that he remembered, too. "By the lord with the great and good mind, I was ," the abbot said slowly. He drew the circular sun-sign on his breast. "You were but a boy then."

It sounded like an accusation. As if to remind himself it was true no more, Krispos touched the hilt of his sword. Thus reassured, he nodded.

"But boy no more," Pyrrhos said, agreeing with him. "Yet here we are, drawn back together once more." He made the sun-sign again, then said something completely obscure to Krispos: "No, Gnatios will not laugh."

"Holy sir?"

"Never mind." The abbot's attention might have wandered for a moment. Now it focused on Krispos again. "Tell me how you came from whatever village you lived in to Videssos the city."

Krispos did. Speaking of his parents' and sister's deaths brought back the pain, nearly as strong as if he felt it for the first time. He had to wait before he could go on. "And then, with the village still all in disarray, our taxes went up a third, I suppose to pay for some war at the other end of the Empire."

"More likely to pay for another—or another dozen—of Anthimos' extravagant follies." Pyrrhos' mouth set in a thin, hard line of disapproval. "Petronas lets him have his way in them, the better to keep the true reins of ruling in his own hands. Neither of them cares how they gain the gold to pay for such sport, so long as they do."

"As may be," Krispos said. "It's not why we were broken, but that we were broken that put me on my way here. Farmers have hard enough times worrying about nature. If the tax man wrecks us, too, we've got no hope at all. That's what it looked like to me, and that's why I left."

Pyrrhos nodded. "I've heard like tales before. Now, though, the question arises of what to do with you. Did you come to the city planning to use the weapons you carry?"

"Not if I can find anything else to do," Krispos said at once.

"Hmm." The abbot stroked his bushy beard. "You lived all your life till now on a farm, yes? How are you with horses?"

"I can manage, I expect," Krispos answered, "though I'm better with mules; I've had more to do with them, if you know what I mean. Mules I'm good with. Any other livestock, too, and I'm your man. Why do you want to know, holy sir?"

"Because I think that, as the flows of your life and mine have come together after so many years, it seems fitting for Iakovitzes' to be mingled with the stream once more, as well. And because I happen to know that Iakovitzes is constantly looking for new grooms to serve in his stables."

"Would he take me on, holy sir? Someone he's never—well, just about never—seen before? If he would ..." Krispos' eyes lit up. "If he would, I'd leap at the chance."

"He would, on my urging," Pyrrhos said. "We're cousins of sorts: his great-grandfather and my grandmother were brother and sister. He also owes me a few more favors than I owe him at the moment."

"If he would, if you would, I couldn't think of anything better. " Krispos meant it; if he was going to work with animals, it would be almost as if he had the best of farm and city both. He hesitated, then asked a question he knew was dangerous: "But why do you want to do this for me, holy sir?"

Pyrrhos sketched the sun-sign. After a moment, Krispos realized that was all the answer he'd get. When the abbot spoke, it was of his cousin. "Understand, young man, you are altogether free to refuse this if you wish. Many would, without a second thought. I don't know if you recall, but Iakovitzes is a man of—how shall I say it?—uncertain temperament, perhaps."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Krispos Rising»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Krispos Rising» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Krispos Rising» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.