John Bowring - A Visit to the Philippine Islands

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Bowring - A Visit to the Philippine Islands» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Visit to the Philippine Islands

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Visit to the Philippine Islands: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Visit to the Philippine Islands»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Visit to the Philippine Islands — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Visit to the Philippine Islands», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The associations and recollections of my youth were revived in the hospitable entertainment of my most excellent host and the courteous and graceful ladies of his family. Nearly fifty years before I had been well acquainted with the Spanish peninsula – in the time of its sufferings for fidelity, and its struggles for freedom, and I found in Manila some of the veterans of the past, to whom the “Guerra de Independencia” was of all topics the dearest; and it was pleasant to compare the tablets of our various memories, as to persons, places and events. Of the actors we had known in those interesting scenes, scarcely any now remain – none, perhaps, of those who occupied the highest position, and played the most prominent parts; but their names still served as links to unite us in sympathizing thoughts and feelings, and having had the advantage of an early acquaintance with Spanish, all that I had forgotten was again remembered, and I found myself nearly as much at home as in former times when wandering among the mountains of Biscay, dancing on the banks of the Guadalquivir, or turning over the dusty tomes at Alcalá de Henares. 3 3 Among my early literary efforts was an essay by which the strange story was utterly disproved of the destruction of the MSS. which had served Cardinal Ximenes in preparing his Polyglot Bible.

There was a village festival at Sampaloc (the Indian name for tamarinds), to which we were invited. Bright illuminations adorned the houses, triumphal arches the streets; everywhere music and gaiety and bright faces. There were several balls at the houses of the more opulent mestizos or Indians, and we joined the joyous assemblies. The rooms were crowded with Indian youths and maidens. Parisian fashions have not invaded these villages – there were no crinolines – these are confined to the capital; but in their native garments there was no small variety – the many-coloured gowns of home manufacture – the richly embroidered kerchiefs of piña – earrings and necklaces, and other adornings; and then a vivacity strongly contrasted with the characteristic indolence of the Indian races. Tables were covered with refreshments – coffee, tea, wines, fruits, cakes and sweetmeats; and there seemed just as much of flirting and coquetry as ever marked the scenes of higher civilization. To the Europeans great attentions were paid, and their presence was deemed a great honour. Our young midshipmen were among the busiest and liveliest of the throng, and even made their way, without the aid of language, to the good graces of the Zagalas . Sampaloc, inhabited principally by Indians employed as washermen and women, is sometimes called the Pueblo de los Lavanderos . The festivities continued to the matinal hours.

In 1855 the Captain-General (Crespo) caused sundry statistical returns to be published, which throw much light upon the social condition of the Philippine Islands, and afford such valuable materials for comparison with the official data of other countries, that I shall extract from them various results which appear worthy of attention.

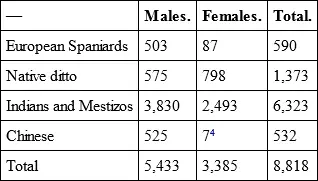

The city of Manila contains 11 churches, with 3 convents, 363 private houses; and the other edifices, amounting in all to 88, consist of public buildings and premises appropriated to various objects. Of the private houses, 57 are occupied by their owners, and 189 are let to private tenants, while 117 are rented for corporate or public purposes. The population of the city in 1855 was 8,618 souls, as follows: —

Примечание 1 4 4 One woman, six children.

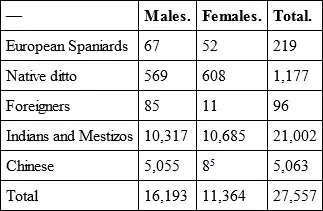

Far different are the proportions in another part of the capital, the Binondo district, on the other side of the river: —

Примечание 1 5 5 All children.

Of these, one male and two females (Indian) were more than 100 years old.

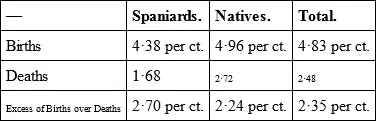

The proportion of births and deaths in Manila is thus given: —

In Binondo the returns are much less favourable: —

The statistical commissioners state these discrepancies to be inexplicable; but attribute it in part to the stationary character of the population of the city, and the many fluctuations which take place in the commercial movements of Binondo.

Binondo is really the most important and most opulent pueblo of the Philippines, and is the real commercial capital: two-thirds of the houses are substantially built of stone, brick and tiles, and about one-third are Indian wooden houses covered with the nipa palm. The place is full of business and activity. An average was lately taken of the carriages daily passing the principal thoroughfares. Over the Puente Grande (great bridge) their number was 1,256; through the largest square, Plaza de S. Gabriel, 979; and through the main street, 915. On the Calzada, which is the great promenade of the capital, 499 carriages were counted – these represent the aristocracy of Manila. There are eight public bridges, and a suspension bridge has lately been constructed as a private speculation, on which a fee is levied for all passengers.

Binondo has some tolerably good wharfage on the bank of the Pasig, and is well supplied with warehouses for foreign commerce. That for the reception of tobacco is very extensive, and the size of the edifice where the state cigars are manufactured may be judged of from the fact that nine thousand females are therein habitually employed.

The Puente Grande (which unites Manila with Binondo) was originally built of wood upon foundations of masonry, with seven arches of different sizes, at various distances. Two of the arches were destroyed by the earthquake of 1824, since which period it has been repaired and restored. It is 457 feet in length and 24 feet in width. The views on all sides from the bridge are fine, whether of the wharves, warehouses, and busy population on the right bank of the river, or the fortifications, churches, convents, and public walks on the left.

The population of Manila and its suburbs is about 150,000.

The tobacco manufactories of Manila, being the most remarkable of the “public shows,” have been frequently described. The chattering and bustling of the thousands of women, which the constantly exerted authority of the female superintendents wholly failed to control, would have been distracting enough from the manipulation of the tobacco leaf, even had their tongues been tied, but their tongues were not tied, and they filled the place with noise. This was strangely contrasted with the absolute silence which prevailed in the rooms solely occupied by men. Most of the girls, whose numbers fluctuate from eight to ten thousand, are unmarried, and many seemed to be only ten or eleven years old. Some of them inhabit pueblos at a considerable distance from Manila, and form quite a procession either in proceeding to or returning from their employment. As we passed through the different apartments specimens were given us of the results of their labours, and on leaving the establishment beautiful bouquets of flowers were placed in our hands. We were accompanied throughout by the superior officers of the administration, explaining to us all the details with the most perfect Castilian courtesy. Of the working people I do not believe one in a hundred understood Spanish.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Visit to the Philippine Islands»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Visit to the Philippine Islands» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Visit to the Philippine Islands» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.