Johann Beckmann - A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Johann Beckmann - A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2) — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“When you wish to use it, you must, in order that the work may be done with more smoothness, employ a brush made of the tail of a certain quadruped called the vari, well-known to those who sell colours for painting; and with this instrument dipped in the liquor wash gently over, three times, the wood which has been silvered. You must, however, remember every time you pass the brush over the wood to let it dry; and thus your work will be extremely beautiful, and have a resemblance to the finest gold.”

After this invention was made known, it was not difficult to vary, by several methods, the manner of preparing it. Different receipts, therefore, have for that purpose been given in a number of books, such as Croker’s Painter, and others: and, on this account, young artists are frequently at a loss which to choose; and when a receipt is found better than another, experienced artists keep it always secret.

With the preparation of that varnish used for gilding leather tapestry Reaumur was acquainted, and from his papers it was made known by Fougeroux de Bondaroy. The method of making the English varnish was communicated by Scarlet to Hellot, in the year 1720; and by Graham to Du Fay, in 1738. In the year 1761, Hellot gave the receipt to the Academy of Sciences at Paris, who published it in their memoirs for that year.

If it be true, as Fougeroux says, that gilded tapestry was made above two hundred years ago, it might be worth the little trouble that such an examination would require to investigate the method used to gild it.

TULIPS

The greater part of the flowers which adorn our gardens have been brought to us from the Levant. A few have been procured from other parts of the world; and some of our own indigenous plants, that grow wild, have, by care and cultivation, been so much improved as to merit a place in our parterres. Our ancestors, perhaps, some centuries ago paid attention to flowers; but it appears that the Orientals, and particularly the Turks, who in other respects are not very susceptible of the inanimate beauties of nature, were the first people who cultivated a variety of them in their gardens for ornament and pleasure. From their gardens, therefore, have been procured the most of those which decorate ours; and amongst these is the tulip.

Few plants acquire through accident, weakness, or disease, so many tints, variegations, and figures, as the tulip. When uncultivated, and in its natural state, it is almost of one colour, has large leaves, and an extraordinary long stem. When it has been weakened by culture, it becomes more agreeable in the eyes of the florist. The petals are then paler, more variegated, and smaller; the leaves assume a fainter or softer green colour: and this masterpiece of culture, the more beautiful it turns, grows so much the weaker; so that, with the most careful skill and attention, it can with difficulty be transplanted, and even scarcely kept alive.

That the tulip grows wild in the Levant, and was thence brought to us, may be proved by the testimony of many writers. Busbequius found it on the road between Adrianople and Constantinople 41; Shaw found it in Syria, in the plains between Jaffa and Rama; and Chardin on the northern confines of Arabia. The early-blowing kinds, it appears, were brought to Constantinople from Cavala, and the late-blowing from Caffa; and on this account the former are called by the Turks Cavalá lalé , and the latter Café lalé . Caval is a town on the eastern coast of Macedonia, of which Paul Lucas gives some account; and Caffa is a town in the Crimea, or peninsula of Gazaria, as it was called, in the middle ages, from the Gazares, a people very little known 42.

Though florists have published numerous catalogues of the species of the tulip, botanists are acquainted only with two, or at most three, of which scarcely one is indigenous in Europe 43. All those found in our gardens have been propagated from the species named after that learned man, to whom natural history is so much indebted, the Linnæus of the sixteenth century, Conrad Gesner, who first made the tulip known by a botanical description and a figure. In his additions to the works of Valerius Cordus, he tells us that he saw the first in the beginning of April 1559, at Augsburg, in the garden of the learned and ingenious counsellor John Henry Herwart. The seeds had been brought from Constantinople, or, according to others, from Cappadocia. This flower was then known in Italy under the name of tulipa, or tulip, which is said to be of Turkish extraction, and given to it on account of its resembling a turban 44.

Balbinus asserts that Busbequius brought the first tulip-roots to Prague, from which they were afterwards spread all over Germany 45. This is not improbable; for Busbequius says, in a letter written in 1554, that this flower was then new to him; and it is known that besides coins and manuscripts he collected also natural curiosities, and brought them with him from the Levant. Nay, he tells us that he paid very dear to the Turks for these tulips; but I do not find he anywhere says that he was the first who brought them from the East.

In the year 1565 there were tulips in the garden of M. Fugger, from whom Gesner wished to procure some 46. They first appeared in Provence, in France, in the garden of the celebrated Peyresc, in the year 1611 47.

After the tulip was known, Dutch merchants, and rich people at Vienna, who were fond of flowers, sent at different times to Constantinople for various kinds. The first roots planted in England were sent thither from Vienna, about the end of the sixteenth century, according to Hakluyt 48; who is, however, wrong in ascribing to Clusius the honour of having first introduced them into Europe; for that naturalist only collected and described all the then known species.

These flowers, which are of no further use than to ornament gardens, which are exceeded in beauty by many other plants, and whose duration is short and very precarious, became, in the middle of the 17th century, the object of a trade such as is not to be met with in the history of commerce, and by which their price rose above that of the most precious metals. An account of this trade has been given by many authors; but by all late ones it has been misrepresented. People laugh at the Tulipomania 49, because they believe that the beauty and rarity of the flowers induced florists to give such extravagant prices: they imagine that the tulips were purchased so excessively dear in order to ornament gardens; but this supposition is false, as I shall show hereafter.

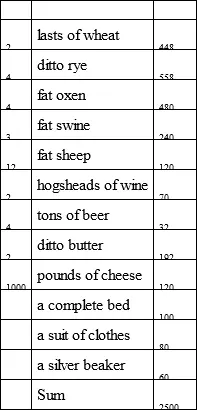

This trade was not carried on throughout all Europe, but in some cities of the Netherlands, particularly Amsterdam, Haarlem, Utrecht, Alkmaar, Leyden, Rotterdam, Hoorn, Enkhuysen, and Meedenblick; and rose to the greatest height in the years 1634–37 50. Munting has given, from some of the books kept during that trade, a few of the prices then paid, of which I shall present the reader with the following. For a root of that species called the Viceroy the after-mentioned articles, valued as below expressed, were agreed to be delivered: —

These tulips afterwards were sold according to the weight of the roots. Four hundred perits 51of Admiral Leifken cost 4400 florins; 446 ditto of Admiral Von der Eyk, 1620 florins; 106 perits Schilder cost 1615 florins; 200 ditto Semper Augustus, 5500 florins; 410 ditto Viceroy, 3000 florins, &c. The species Semper Augustus has been often sold for 2000 florins; and it once happened that there were only two roots of it to be had, the one at Amsterdam and the other at Haarlem. For a root of this species, one agreed to give 4600 florins, together with a new carriage, two gray horses, and a complete harness. Another agreed to give for a root twelve acres of land; for those who had not ready money, promised their moveable and immoveable goods, houses and lands, cattle and clothes. A man whose name Munting once knew, but could not recollect, won by this trade more than 60,000 florins in the course of four months. It was followed not only by mercantile people, but also by the first noblemen, citizens of every description, mechanics, seamen, farmers, turf-diggers, chimney-sweeps, footmen, maid-servants and old clothes-women, &c. At first, every one won and no one lost. Some of the poorest people gained in a few months houses, coaches and horses, and figured away like the first characters in the land. In every town some tavern was selected which served as a ’Change, where high and low traded in flowers, and confirmed their bargains with the most sumptuous entertainments. They formed laws for themselves, and had their notaries and clerks.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins, Volume I (of 2)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.