George Elliot - The Romance of Plant Life

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «George Elliot - The Romance of Plant Life» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Romance of Plant Life

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Romance of Plant Life: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Romance of Plant Life»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Romance of Plant Life — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Romance of Plant Life», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Theophrastus, who flourished about 300 B.C., was a scientific botanist far ahead of his time. His notes about the mangroves in the Persian gulf are still of some importance. It is said that some two thousand botanical students attended his lectures. 7 7 Lascelles, Pharm. Journ. , 23 May, 1903.

It is doubtful if any professor of botany has ever since that time had so large a number of pupils. Dioscorides, who lived about 64 B.C., wrote a book which was copied by the Pliny (78 A.D.), who perished in the eruption of Vesuvius. The botany of the Middle Ages seems to have been mainly that of Theophrastus and Dioscorides. In the tenth century we find an Arab, Ibn Sina, whose name has been commemorated in the name of a plant, Avicennia, publishing the first illustrated text-book, for he gave coloured diagrams to his pupils.

After this there was exceedingly little discovery until comparatively recent times.

But Grew in 1682 and Malpighi in 1700 began to work with the microscope, and with the work of Linnæus in 1731 modern botany was well started and ready to develop. 8 8 Bonnier, Cours de Botanique .

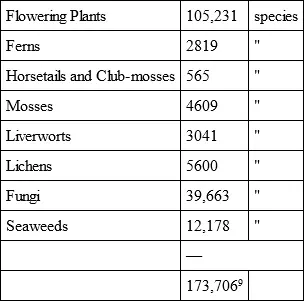

It is interesting to compare the numbers of plants known at various periods, so as to see how greatly our knowledge has been increased of recent years. Theophrastus (300 B.C.) knew about 500 plants. Pliny (78 A.D.) knew 1000 species by name. Linnæus in 1731 raised the number to 10,000. Saccardo in 1892 gives the number of plants then known as follows: —

9. Saccardo, Atti d. Congresso, Bot. Intern. di Genova , 1892.

But, during the years that have elapsed since 1892, many new species have been described, so that we may estimate that at least 200,000 species are now known to mankind.

But it is in the inner meaning and general knowledge of the life of plants that modern botany has made the most extraordinary progress. It is true that we are still burdened with medieval terminology. There are such names as "galbulus," "amphisarca," and "inferior drupaceous pseudocarps," but these are probably disappearing.

The great ideas that plants are living beings, that every detail in their structure has a meaning in their life, and that all plants are more or less distant cousins descended from a common ancestor, have had extraordinary influence in overthrowing the unintelligent pedantry so prevalent until 1875.

Yet there were many, not always botanists, of much older date, who made great discoveries in the science. Leonardo da Vinci, the great painter, seems to have had quite a definite idea of the growth of trees, for he found out that the annual rings on a tree-stem are thin on the northern and thick on the southern side of the trunk. Dante 10 10 "Guarda il calor del sol che si fa vino Giunto all' umor che dalla vite cola." He is speaking of wine – that "lovable blood," as he describes it.

seems to have also understood the effect of sunlight in ripening the vine and producing the growth of plants ( Purgatorio , xxv. 77). Goethe seems to have been almost the first to understand how leaves can be changed in appearance when they are intended to act in a different way. Petals, stamens, as well as some tendrils and spines, are all modified leaves. There is also a passage in Virgil, or perhaps more distinctly in Cato, which is held to show that the ancients knew that the group of plants, Leguminosæ , in some way improved the soil. I have also tried to show that Shelley had a more or less distinct idea of the "warning" or conspicuous colours (reds, purples, spotted, and speckled) which are characteristic of many poisonous plants (see p. 238 Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес». Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес. Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

).

But if we begin with the unlettered savage, one can trace the very slow and gradual growth of the science of plant-life persisting all through the Dark Ages, the Middle Ages, and recent times, until about fifty or sixty years ago, when a sudden great development began, which gives us, we hope, the promise of still more wonderful discoveries.

CHAPTER III

A TREE'S PERILOUS LIFE

Hemlock spruce and pine forests – Story of a pine seedling – Its struggles and dangers – The gardener's boot – Turpentine of pines – The giant sawfly – Bark beetles – Their effect on music – Storm and strength of trees – Tall trees and long seaweeds – Eucalyptus, big trees – Age of trees – Venerable sequoias, oaks, chestnuts, and olives – Baobab and Dragontree – Rabbits as woodcutters – Fire as protection – Sacred fires – Dug-out and birch-bark canoes – Lake dwellings – Grazing animals and forest destruction – First kind of cultivation – Old forests in England and Scotland – Game preserving.

"The murmuring pines and the hemlocks

Stand like harpers hoar with beards that rest on their bosom." — Longfellow.

OF course the Hemlock here alluded to is not the "hemlock rank growing on the weedy bank," which the cow is adjured not to eat in Wordsworth's well-known lines. (If the animal had, however, obeyed the poet's wishes and eaten "mellow cowslips," it would probably have been seriously ill.) The "Hemlock" is the Hemlock spruce, a fine handsome tree which is common in the forests of Eastern North America.

These primeval forests of Pine and Fir and Spruce have always taken the fancy of poets. They are found covering craggy and almost inaccessible mountain valleys; even a tourist travelling by train cannot but be impressed by their sombre, gloomy monotony, by their obstinacy in growing on rocky precipices on the worst possible soil, in spite of storm and snow.

But to realize the romance of a Pine forest, it is necessary to tramp, as in Germany one sometimes has to do, for thirty miles through one unending black forest of Coniferous trees; there are no towns, scarcely a village or a forester's hut. The ground is covered with brown, dead needles, on which scarcely even green moss can manage to live.

Then one realizes the irritating monotony of the branches of Pines and Spruces, and their sombre, dark green foliage produces a morose depression of spirit.

The Conifers are, amongst trees, like those hard-set, gloomy, and determined Northern races whose life is one long, continuous strain of incessant endeavour to keep alive under the most difficult conditions.

From its very earliest infancy a young Pine has a very hard time. The Pine-cones remain on the tree for two years. The seeds inside are slowly maturing all this while, and the cone-scales are so welded or soldered together by resin and turpentine that no animal could possibly injure them. How thorough is the protection thus afforded to the young seeds, can only be understood if one takes a one-year-old unopened cone of the Scotch Fir and tries to get them out. It does not matter what is used; it may be a saw, a chisel, a hammer, or an axe: the little elastic, woody, turpentiny thing can only be split open with an infinite amount of trouble and a serious loss of calm.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Romance of Plant Life»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Romance of Plant Life» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Romance of Plant Life» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.