Sidney Endle - The Kacháris

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sidney Endle - The Kacháris» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Kacháris

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Kacháris: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Kacháris»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Kacháris — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Kacháris», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Origin, &c. II. The origin of the Kachári race is still very largely a matter of conjecture and inference, in the absence of anything entitled to be regarded as authentic history. As remarked above, in feature and general appearance they approximate very closely to the Mongolian type; and this would seem to point to Tibet and China as the original home of the race. The Garos, a race obviously near of kin to the Kacháris, have a tradition that in the dim and distant past their forefathers, i. e. , nine headmen, the offspring of a Hindu fakir and a Tibetan woman, came down from the northern mountains, and, after a halt at Koch-Behar, made their way to Jogighopa, and thence across the Brahmaputra to Dalgoma, and so finally into the Garo Hills. It is not easy to say what degree of value is to be attached to this tradition, but it does at least suggest a line of inquiry that might well be followed up with advantage. 2 2 Some interesting remarks on this subject will be found in the Garo monograph. – [Ed.]

It is possible that there were at least two great immigrations from the north and north-east into the rich valley of the Brahmaputra, i. e. , one entering North-east Bengal and Western Assam through the valley of the Tista, Dharla, Sankosh, &c., and founding there what was formerly the powerful kingdom of Kāmārūpa; and the other making its way through the Subansiri, Dibong and Dihong valleys into Eastern Assam, where a branch of the widespread Kachári race, known as Chutiyás, undoubtedly held sway for a lengthened period. The capital quarters of this last-mentioned people (the Chutiyás) was at or near the modern Sadiya, not far from which certain ruins of much interest, including a copper-roofed temple ( Támár ghar ), are still to be seen. It is indeed not at all unlikely that the people known to us as Kacháris and to themselves as Baḍa (Bara), were in earlier days the dominant race in Assam; and as such they would seem to have left traces of this domination in the nomenclature of some of the physical features of the country, e. g. , the Kachári word for water ( di ; dŏi ) apparently forms the first syllable of the names of many of the chief rivers of the province, such as Diputá, Dihong, Dibong, Dibru, Dihing, Dimu, Desáng, Diku ( cf. khu Tista), &c., and to these may be added Dikrang, Diphu, Digáru, &c., all near Sadiya, the earliest known centre of Chutiyá (Kachári) power and civilisation.

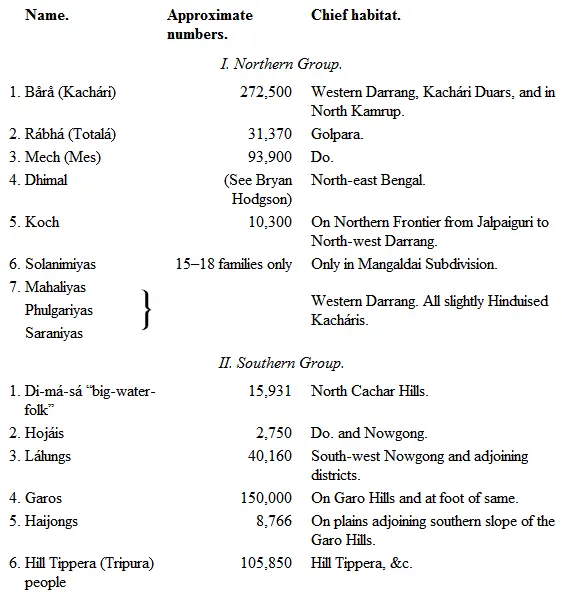

Distribution. III. But however this may be, there would seem to be good reason for believing that the Kachári (Baḍa) race is a much more widely distributed one than it was at one time supposed to be. They are undoubtedly found well outside the limits of modern (political) Assam, i. e. , in North-east Bengal Koch-Behar, &c., and also in Hill Tippera, where the language of the people gives decisive evidence that they are of the Baḍa stock. But apart from these outlying members of the race, there are within the limits of Assam itself at least 1,000,000 souls, probably many more, who belong to the Kachári race; though many of the number have of late years become more or less Hinduised, and have lost the use of their mother tongue. These may perhaps be conveniently divided into a (1) Northern and (2) a Southern group, the Brahmaputra being taken roughly as the dividing line, thus: —

To these may be added one or two smaller communities, e. g. , the Moráns and the Chutiyás in Upper Assam, whose language, not altogether extinct as yet though apparently dying out rapidly, would seem to prove them to be closely akin to the Kachári (Baḍa) race.

Historic Sketch. IV. The only branch of this widely spread race that may be said to have anything like an authentic history is that settled in what is known as the once powerful kingdom of Kāmārūpa (Koch), the reigning family of which is now represented by the Rajas of Koch-Behar, Bijni, Darrang (Mangaldai) and Beltola. But on the history of this (the Western) section of the Kachári race there is no need to dwell, as it was very effectively dealt with some few years ago. 3 3 See “Koch Kings of Kamrup,” by E. A. Gait, Esq., I.C.S., Assam Secretariat Press P.O., 1895.

But the earliest historical notices of the Eastern branch of the race show that under the name of Chutiyás they had established a powerful kingdom in the Eastern corner of the Province, the seat of Government being at or near the modern Sadiya. How long this kingdom existed it is now impossible to say; but what is known with some degree of certainty is, that they were engaged in a prolonged struggle with the Ahoms, a section of the great Shan (Tai) race, who crossed the Pátkoi Hills from the South and East about A.D. 1228, and at once subdued the Moráns, Boráhis, and other Kachári tribes living near the Northern slope of these hills. With the Chutiyás the strife would seem to have been a long and bitter one, lasting for some 150 or 200 years. But in the end the victory remained with the Ahoms, who drove their opponents to take refuge in or about Dimápur on the Dhansiri at the foot of the Naga Hills. There for a time the fugitives were in comparative security and they appear to have attained to a certain measure of material civilisation, a state of things to which some interesting remains of buildings (never as yet properly explored) seem to bear direct and lasting witness. Eventually, however, their ancient foes followed them up to their new capital, and about the middle of the sixteenth century the Ahoms succeeded in capturing and sacking Dimápur itself. The Kachári Raja thereupon removed his court to Máibong (“much paddy”), where the dynasty would seem to have maintained itself for some two centuries. Finally, however, under pressure of an attack by the Jaintia Raja the Kachári sovereign withdrew from Máibong to Kháspur in Kachar ( circa 1750 A.D.). There they seem to have come more and more under Hindu influence, until about 1790 the Raja of that period, Krishna Chandra, and his brother Govinda Chandra made a public profession of Brahminism. They were both placed for a time inside the body of a large copper image of a cow, and on emerging thence were declared by the Brahmins to be Hindus of the Kshatriya caste, Bhīma of Mahābhārat fame being assigned to them as a mythological ancestor. Hence to this day the Darrang Kacháris sometimes speak of themselves as “Bhīm-nī-fsā,” i. e. children of Bhīm, though as a rule they seem to attach little or no value to this highly imaginative ancestry.

The reign of the last Kachári king, Govind Chandra, was little better than one continuous flight from place to place through the constant attacks of the Burmese, who finally compelled the unhappy monarch to take refuge in the adjoining British district of Sylhet. He was, indeed, reinstated in power by the aid of the East India Company’s troops in 1826, but was murdered some four years later, when his kingdom became part of the British dominions. His commander-in-chief, one Tulá Rám, was allowed to remain in possession of a portion of the subdivision now known as North Cachar, a region shown in old maps of Assam as “Tula Ram Senapati’s country.” But on the death of this chieftain in 1854, this remaining portion of the old Kachári Raj was formally annexed to the district of Nowgong.

As regards this last-mentioned migration, i. e. , from Maibong to Kháspur about A.D. 1750, and the conversion to Hinduism which soon followed it, it would seem that the movement was only a very limited and restricted one, confined indeed very largely to the Raja and the members of his court. The great majority of his people remained in the hill country, where to this day they retain their language, religion, customs, &c., to a great extent intact. It is not improbable, indeed, that this statement may hold good of the earlier migrations also, i. e. , those that resulted from the prolonged struggle between the Ahoms and the Chutiyás. When as a result of that struggle the defeated race withdrew first to Dimápur and afterwards to Máibong, it is not unlikely that the great body of the Chutiyás (Kacháris) which remained in the rich valley of Assam came to terms with their conquerors (the Ahoms) and gradually became amalgamated with them, much as Saxons, Danes, Normans, &c., slowly but surely became fused into one nationality in the centuries following the battle of Hastings. In this way it may well be that the Kachári race were the original autochthones of Assam, and that even now, though largely Hinduised, they still form a large, perhaps the main, constituent element in the permanent population of the Province. To this day one often comes across villages bearing the name of “Kachárigaon,” the inhabitants of which are completely Hinduised, though for some considerable time they would seem to have retained their Kachári customs, &c., unimpaired. It may be that, whilst the great body of the Chutiyá (Kachári) race submitted to their Ahom conquerors, the stronger and more patriotic spirits among them, influenced perhaps by that intense clannishness which is so marked a feature in the Kachári character, withdrew to less favoured parts of the Province, where their conquerors did not care at once to follow them up; i. e. , the Southern section of the race may have made its way into the districts known as the Garo Hills and North Cachar; whilst the Northern section perhaps took up its abode in a broad belt of country at the foot of the Bhutan Hills, still known as the “Kachári Duars,” a region which, being virtually “Terai” land, had in earlier days a very unenviable reputation on the score of its recognised unhealthiness. And if this view of the matter be at all a sound one, what is known to have happened in our own island may perhaps furnish a somewhat interesting “historic parallel.” When about the middle of the fifth century the Romans finally withdrew from Britain, we know that successive swarms of invaders, Jutes, Danes, Saxons, Angles, &c., from the countries adjoining the North and Baltic seas, gradually overran and occupied the richer lowland of what is now England, driving all who remained alive of the aboriginal Britons to take refuge in the less favoured parts of the country, i. e. , the mountains of Wales and the highlands of Scotland, where many of the people of this day retain their ancient mother speech: very much as the Kacháris of Assam still cling to their national customs, speech, religion, &c., in those outlying parts of the Province known in modern times as the Garo Hills, North Cachar and the Kachári Duars of North-west Assam.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Kacháris»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Kacháris» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Kacháris» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.