Robert Ferguson - Surnames as a Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Ferguson - Surnames as a Science» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Surnames as a Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Surnames as a Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Surnames as a Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Surnames as a Science — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Surnames as a Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Anglo-Saxon names. – Gæcg, Geagga, Geah, Cæg, Ceagga, Ceahha (Gæging, Gaing, patronymics ).

Old German names. – Gaio, Geio, Kegio, Keyo, Keio.

Present German. – Gey, Geu.

Present Friesic. – Kay, Key.

English surnames. – Gay, Gye, Gedge, Gage, Kay, Key, Kegg, Kedge, Cage.

As to the origin and meaning of the word, I can offer nothing more than a somewhat speculative conjecture. There is a stem gagen , cagen , in Teutonic names, and which seems to be derived most probably from O.N. gagn , gain, victory. We find it in Anglo-Saxon in Gegnesburh, now Gainsborough, and in Geynesthorn, another place-name, and we have it in our names Gain , Cain , Cane . It is very possible, and in accordance with the Teutonic system, that gag may represent the older and simpler form, standing to gagen in the same relation as English ward does to warden , and A.S. geard (inclosure), to garden .

As in the two previous cases, so also in this case, there is an ancient Celtic name, Geio, to take into account, and to this may be placed the names Keogh and Keho , if these names be, as I suppose, Irish and not English. Also the Kay and the Kie in McKay and McKie . Lastly, in this, as in the other two cases, there is also a name on Roman pottery, Gio, which might, as it seems, be either German or Celtic. Can there be any connection, I venture to inquire, between these ancient names, Celtic or Teutonic, and the Roman Gaius and Caius? Several well-known Roman names are, as elsewhere noted, referred by German writers to a Celtic origin.

It will be seen then that, in the case of all the three names of which I have been treating, there is an ancient Celtic name in a corresponding form which might in some cases intermix. And there are many more cases of the same kind among our surnames. Wake , for instance, may represent an ancient name, either German or Celtic; for the German a sufficient etymon may be found in wak , watchful, while for the Celtic there is nothing, observes Gluck, in the range of extant dialects to which we can reasonably refer it. So Moore represents an ancient stem for names common to the Celts, the Germans, and the Romans, though at least as regards the Germans, the origin seems obscure. 3 3 So at least Foerstemann seems to think, observing that we can scarcely derive it from Maur, Æthiops, English "Moor." Nevertheless, seeing the long struggle between the Teutons and the Moors in Spain, it seems to me that such a derivation would be quite in accordance with Teutonic practice. See some remarks on the general subject at the end of Chapter IV.

Now it is quite possible, particularly in the case of such monosyllabic words as these, that there might be an accidental coincidence between a Celtic and a Teutonic name, without their having anything in common in their root. It is possible, again, that the one nation may have borrowed a name from the other, as the Northmen, for instance, sometimes did from the Irish or the Gael, one of their most common names, Niel(sen), being thus derived; while, on the other hand, both the Irish and the Gael received, as Mr. Worsaae has shown, many names from the Northmen. So also the Romans seem to have borrowed names from the Celts, several well-known names, as Plinius, Livius, Virgilius, 4 4 So that we may take it that Virgilius, as the name of a Scot who became bishop of Salzburg in the time of Boniface, was his own genuine Celtic name, and not derived from that of the Roman poet.

Catullus, and Drusus, being, in the opinion of German scholars, thus derived.

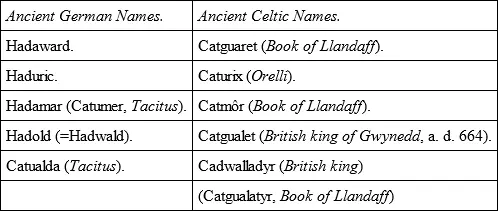

But though no doubt both these principles apply to the present case, yet there is also, as it seems to me, something in the relationship between Celtic and Teutonic names which can hardly be accounted for on either of the above principles. And I venture to throw out the suggestion that when ancient Celtic names shall have been as thoroughly collected and examined as, by the industry of the Germans, have been the Teutonic, comparative philology may – perhaps within certain lines – find something of the same kinship between them that it has already established in the case of the respective languages. Meanwhile, I venture to put forward, derived from such limited observations as I have been able to make, certain points of coincidence which I think go some way to justify the opinion expressed above. In so doing I am not so much putting forward etymological views of my own, as collecting together, so as to shape them into a comparison, the conclusions which have, in various individual cases, been arrived at by scholars such as Zeuss. There are, then, four very common endings in Teutonic names, — ward , as in Edward, ric , as in Frederic, mar , as in Aylmar, and wald , as in Reginald (=Reginwald). The same four words, in their corresponding forms, are also common as the endings of Celtic names, ward taking the form of guared or guaret , the German ric taking generally the form of rix (which appears also to have been the older form in the German, all names of the first century being so given by Latin authors), wald taking the form of gualed or gualet , and mar being pretty much the same in both. Of these four cases of coincidence, there is only one ( wald = gualet ) which I have not derived from German authority. And with respect to this one, I have assumed the Welsh gualed , order, arrangement, whence gualedyr , a ruler, to be the same word as German wald , Gothic valdan , to rule. But we can carry this comparison still further, and show all these four endings in combination with one and the same prefix common to both tongues. This prefix is the Old German had , hat , hath , signifying war, the corresponding word to which is in Celtic cad or cat . (Note that in the earliest German names on record, as the Catumer and the Catualda of Tacitus, the German form is cat , same as the Celtic. This seems to indicate that at that early period the Germans so strongly aspirated the h in hat , that the word sounded to Roman ears like cat , and it assists perhaps to give us an idea of the way in which such variations of tongues arise.)

I subjoin then the following names which, mutatis mutandis , are the same in both tongues, and which, judging them by the same rules which philology has applied to the respective languages, might be taken to be from some earlier source common to both races: —

In comparing Catualda with the British Cadwalladyr I am noting an additional point of coincidence. Catualda is not, like other Old German names, from wald , rule, but from walda , ruler. There is only one other Old German name in the same form, Cariovalda, 5 5 This name, that of a prince of the Batavi, is considered by the Germans to be properly Hariovalda, from har , army, and hence is another instance of an initial h being represented among the Romans by a c . The name is the same as the Anglo-Saxon Harald, and as our present name Harold .

also a very ancient name, being of the first century. This then may represent the older form, though this is not what I wish at present to note, but that Catualda is the counterpart of the British Cadwalladyr, which also is not from gualed , rule, but from gualedyr , ruler.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Surnames as a Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Surnames as a Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Surnames as a Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.