George Dodd - The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «George Dodd - The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Again is the search baffled. We find in the minute proofs only that India had become great and grand; if the seeds of rebellion existed, they were buried under the language which described material and social advancement. Is it that England, in 1856, had yet to learn to understand the native character? Such may be; for thuggee came to the knowledge of our government with astounding suddenness; and there may be some other kind of thuggee, religious or social, still to be learned by us. Let us bear in mind what this thuggee or thugism was, and who were the Thugs. Many years ago, uneasy whispers passed among the British residents in India. Rumours went abroad of the fate of unsuspecting travellers ensnared while walking or riding upon the road, lassoed or strangled by means of a silken cord, and robbed of their personal property; the rumours were believed to be true; but it was long ere the Indian government succeeded in bringing to light the stupendous conspiracy or system on which these atrocities were based. It was then found that there exists a kind of religious body in India, called Thugs, among whom murder and robbery are portions of a religious rite, established more than a thousand years ago. They worship Kali, one of the deities of the Hindoo faith. In gangs varying from ten to two hundred, they distribute themselves – or rather did distribute themselves, before the energetic measures of the government had nearly suppressed their system – about various parts of India, sacrificing to their tutelary goddess every victim they can seize, and sharing the plunder among themselves. They shed no blood, except under special circumstances; murder being their religion, the performance of its duties requires secrecy, better observed by a noose or a cord than by a knife or firearm. Every gang has its leader, teacher, entrappers, stranglers, and gravediggers; each with his prescribed duties. When a traveller, supposed or known to have treasure about him, has been inveigled to a selected spot by the Sothas or entrappers, he is speedily put to death quietly by the Bhuttotes or stranglers, and then so dexterously placed underground by the Lughahees or gravediggers that no vestige of disturbed earth is visible. 1 1 The visitor to the British Museum, in one of the saloons of the Ethnological department, will find a very remarkable series of figures, modelled by a native Hindoo, of the individuals forming a gang of Thugs; all in their proper costumes, and all as they are (or were) usually engaged in the successive processes of entrapping, strangling, and burying a traveller, and then dividing the booty.

This done, they offer a sacrifice to their goddess Kali, and finally share the booty taken from the murdered man. Although the ceremonial is wholly Hindoo, the Thugs themselves comprise Mohammedans as well as Hindoos; and it is supposed by some inquirers that the Mohammedans have ingrafted a system of robbery on that which was originally a religious murder – murder as part of a sacrifice to a deity.

We repeat: there may be some moral or social thuggee yet to be discovered in India; but all we have now to assert is, that the condition of India in 1856 did not suggest to the retiring governor-general the slightest suspicion that the British in that country were on the edge of a volcano. He said, in closing his remarkable minute: ‘My parting hope and prayer for India is, that, in all time to come, these reports from the presidencies and provinces under our rule may form, in each successive year, a happy record of peace, prosperity, and progress.’ No forebodings here, it is evident. Nevertheless, there are isolated passages which, read as England can now read them, are worthy of notice. One runs thus: ‘No prudent man, who has any knowledge of Eastern affairs, would ever venture to predict the maintenance of continued peace within our Eastern possessions. Experience, frequent hard and recent experience, has taught us that war from without, or rebellion from within, may at any time be raised against us, in quarters where they were the least to be expected, and by the most feeble and unlikely instruments. No man, therefore, can ever prudently hold forth assurance of continued peace in India.’ Again: ‘In territories and among a population so vast, occasional disturbance must needs prevail. Raids and forays are, and will still be, reported from the western frontier. From time to time marauding expeditions will descend into the plains; and again expeditions to punish the marauders will penetrate the hills. Nor can it be expected but that, among tribes so various and multitudes so innumerable, local outbreaks will from time to time occur.’ But in another place he seeks to lessen the force and value of any such disturbances as these. ‘With respect to the frontier raids, they are and must for the present be viewed as events inseparable from the state of society which for centuries past has existed among the mountain tribes. They are no more to be regarded as interruptions of the general peace in India, than the street-brawls which appear among the everyday proceedings of a police-court in London are regarded as indications of the existence of civil war in England. I trust, therefore, that I am guilty of no presumption in saying, that I shall leave the Indian Empire in peace, without and within.’

Such, then, is a governor-general’s picture of the condition of the British Empire in India in the spring of 1856: a picture in which there are scarcely any dark colours, or such as the painter believed to be dark. We may learn many things from it: among others, a consciousness how little we even now know of the millions of Hindostan – their motives, their secrets, their animosities, their aspirations. The bright picture of 1856, the revolting tragedies of 1857 – how little relation does there appear between them! That there is a relation all must admit, who are accustomed to study the links of the chain that connect one event with another; but at what point the relation occurs, is precisely the question on which men’s opinions will differ until long and dispassionate attention has been bestowed on the whole subject.

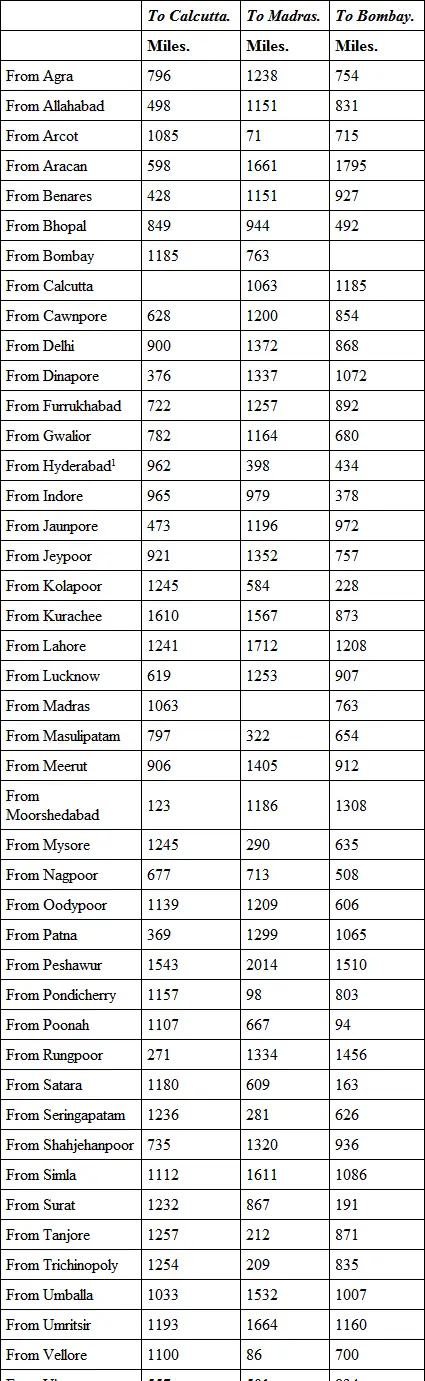

[This may be a convenient place in which to introduce a few observations on three subjects likely to come with much frequency under the notice of the reader in the following chapters; namely, the distances between the chief towns in India and the three great presidential cities – the discrepancies in the current modes of spelling the names of Indian persons and places – and the meanings of some of the native words frequently used in connection with Indian affairs.]

Distances. – For convenience of occasional reference, a table of some of the distances in India is here given. It has been compiled from the larger tables of Taylor, Garden, Hamilton, and Parbury. Many of the distances are estimated in some publications at smaller amount, owing, it may be, to the opening of new and shorter routes:

1There are two Hyderabads – one in the Nizam’s dominions in the Deccan, and the other in Sinde (spelt Hydrabad): it is the former here intended.

Orthography. – It is perfectly hopeless to attempt here any settlement of the vexed question of Oriental orthography, the spelling of the names of Indian persons and places. If we rely on one governor-general, the next contradicts him; the commander-in-chief very likely differs from both; authors and travellers have each a theory of his own; while newspaper correspondents dash recklessly at any form of word that first comes to hand. Readers must therefore hold themselves ready for these complexities, and for detecting the same name under two or three different forms. The following will suffice to shew our meaning: – Rajah, raja – nabob, nawab, nawaub – Punjab, Punjaub, Penjab, Panjab – Vizierabad, Wuzeerabad – Ghengis Khan, Gengis Khan, Jengis Khan – Cabul, Caboul, Cabool, Kabul – Deccan, Dekkan, Dukhun – Peshawur, Peshawar – Mahomet, Mehemet, Mohammed, Mahommed, Muhummud – Sutlej, Sutledge – Sinde, Scinde, Sindh – Himalaya, Himmaléh – Cawnpore, Cawnpoor – Sikhs, Seiks – Gujerat, Guzerat – Ali, Alee, Ally – Ghauts, Gauts – Sepoys, Sipahis – Faquir, Fakeer – Oude, Oudh – Bengali, Bengalee – Burhampooter, Brahmaputra – Asam, Assam – Nepal, Nepaul – Sikkim, Sikim – Thibet, Tibet – Goorkas, Ghoorkas – Cashmere, Cashmeer, Kashmir – Doab, Dooab – Sudra, Soodra – Vishnu, Vishnoo – Buddist, Buddhist, &c. Mr Thornton, in his excellent Gazetteer of India, gives a curious instance of this complexity, in eleven modes of spelling the name of one town, each resting on some good authority – Bikaner, Bhicaner, Bikaneer, Bickaneer, Bickanere, Bikkaneer, Bhikanere, Beekaneer, Beekaner, Beykaneer, Bicanere. One more instance will suffice. Viscount Canning, writing to the directors of the East India Company concerning the conduct of a sepoy, spelled the man’s name Shiek Paltoo . A fortnight afterwards, the same governor-general, writing to the same directors about the same sepoy, presented the name under the form Shaik Phultoo . We have endeavoured as far as possible to make the spelling in the narrative and the map harmonise.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.