George Dodd - The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «George Dodd - The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With a governor-general a thousand miles away, the chief officers at and near Kurnaul settled among themselves as best they could, according to the rules of the service, the distribution of duties, until official appointments could be made from Calcutta. Major-general Sir Henry Barnard became temporary commander, and Major-general Reid second under him. When the governor-general received this news, he sent for Sir Patrick Grant, a former experienced adjutant-general of the Bengal army, from Madras, to assume the office of commander-in-chief; but the officers at that time westward of Delhi – Barnard, Reid, Wilson, and others – had still the responsibility of battling with the rebels. Sir Henry Barnard, as temporary chief, took charge of the expedition to Delhi – with what results will be shewn in the proper place.

The regions lying west, northwest, and southwest of Delhi have this peculiarity, that they are of easier access from Bombay or from Kurachee than from Calcutta. Out of this rose an important circumstance in connection with the Revolt – namely, the practicability of the employment of the Bombay native army to confront the mutinous regiments belonging to that of Bengal. It is difficult to overrate the value of the difference between the two armies. Had they been formed of like materials, organised on a like system, and officered in a like ratio, the probability is that the mutiny would have been greatly increased in extent – the same motives, be they reasonable or unreasonable, being alike applicable to both armies. Of the degree to which the Bombay regiments shewed fidelity, while those of Bengal unfurled the banner of rebellion, there will be frequent occasions to speak in future pages. The subject is only mentioned here to explain why the western parts of India are not treated in the present chapter. There were, it is true, disturbances at Neemuch and Nuseerabad, and at various places in Rajpootana, the Punjaub, and Sinde; but these will better be treated in later pages, in connection rather with Bombay than with Calcutta as head-quarters. Enough has been said to shew over how wide an area the taint of disaffection spread during the month of May – to break out into something much more terrible in the next following month.

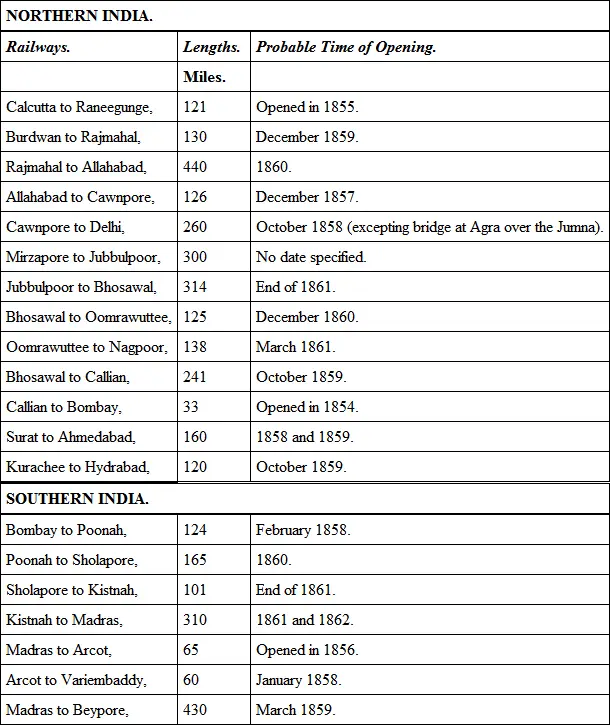

Indian Railways. – An interesting question presents itself, in connection with the subject of the present chapter – Whether the Revolt would have been possible had the railways been completed? The rebels, it is true, might have forced up or dislocated the rails, or might have tampered with the locomotives. They might, on the other hand, if powerfully concentrated, have used the railways for their own purposes, and thus made them am auxiliary to rebellion. Nevertheless, the balance of probability is in favour of the government – that is, the government would have derived more advantage than the insurgents from the existence of railways between the great towns of India. The difficulties, so great as to be almost insuperable, in transporting troops from one place to another, have been amply illustrated in this and the preceding chapters; we have seen how dâk and palanquin bearers, bullocks and elephants, ekahs and wagons, Ganges steamers and native boats, were brought into requisition, and how painfully slow was the progress made. The 121 miles of railway from Calcutta to Raneegunge were found so useful, in enabling the English soldiers to pass swiftly over the first part of their journey, that there can hardly be a doubt of the important results which would have followed an extension of the system. Even if a less favourable view be taken in relation to Bengal and the Northwest Provinces, the advantages would unquestionably have been on the side of the government in the Bombay and Madras presidencies, where disaffection was shewn only in a very slight degree; a few days would have sufficed to send troops from the south of India by rail, viâ Bombay and Jubbulpoor to Mirzapore, in the immediate vicinity of the regions where their services were most needed.

Although the Raneegunge branch of the East Indian Railway was the only portion open in the north of India, there was a section of the main line between Allahabad and Cawnpore nearly finished at the time of the outbreak. This main line will nearly follow the course of the Ganges, from Calcutta up to Allahabad; it will then pass through the Doab, between the Ganges and the Jumna, to Agra; it will follow the Jumna from Agra up to Delhi; and will then strike off northwestward to Lahore – to be continued at some future time through the Punjaub to Peshawur. During the summer of 1857, the East India Company prepared, at the request of parliament, an exact enumeration of the various railways for which engineering plans had been adopted, and for the share-capital of which a minimum rate of interest had been guaranteed by the government. The document gives the particulars of about 3700 miles of railway in India; estimated to cost £30,231,000; and for which a dividend is guaranteed to the extent of £20,314,000, at a rate varying from 4½ to 5 per cent. The government also gives the land, estimated to be worth about a million sterling. All the works of construction are planned on a principle of solidity, not cheapness; for it is expected they will all be remunerative. Arrangements are everywhere made for a double line of rails – a single line being alone laid down until the traffic is developed. The gauge is nine inches wider than the ‘narrow gauge’ of English railways. The estimated average cost is under £9000 per mile, about one-fourth of the English average.

Leaving out of view, as an element impossible to be correctly calculated, the amount of delay arising from the Revolt, the government named the periods at which the several sections of railway would probably be finished. Instead of shewing the particular portions belonging respectively to the five railway companies – the East Indian, the Great Indian Peninsula, the Bombay and Central India, the Sinde, and the Madras – we shall simply arrange the railways into two groups, north and south, and throw a few of the particulars into a tabulated form.

The plans for an Oude railway were drawn up, comprising three or four lines radiating from Lucknow; but the project had not, at that time, assumed a definite form.

’Headman’ of a Village. – It frequently happened, in connection with the events recorded in the present chapter, that the headman of a village either joined the mutineers against the British, or assisted the latter in quelling the disturbances; according to the bias of his inclination, or the view he took of his own interests. The general nature of the village-system in India requires to be understood before the significancy of the headman’s position can be appreciated. Before the British entered India, private property in land was unknown; the whole was considered to belong to the sovereign. The country was divided, by the Mohammedan rulers, into small holdings, cultivated each by a village community under a headman; for which a rent was paid. For convenience of collecting this rent or revenue, zemindars were appointed, who either farmed the revenues, or acted simply as agents for the ruling power. When the Marquis of Cornwallis, as governor-general, made great changes in the government of British India half a century ago, he modified, among other matters, the zemindary; but the collection of revenue remained.

Whether, as some think, villages were thus formed by the early conquerors; or whether they were natural combinations of men for mutual advantage – certain it is that the village-system in the plains of Northern India was made dependent in a large degree on the peculiar institution of caste. ‘To each man in a Hindoo village were appointed particular duties which were exclusively his, and which were in general transmitted to his descendants. The whole community became one family, which lived together and prospered on their public lands; whilst the private advantage of each particular member was scarcely determinable. It became, then, the fairest as well as the least troublesome method of collecting the revenue to assess the whole village at a certain sum, agreed upon by the tehsildar (native revenue collector) and the headman. This was exacted from the latter, who, seated on the chabootra, in conjunction with the chief men of the village, managed its affairs, and decided upon the quota of each individual member. By this means, the exclusive character of each village was further increased, until they have become throughout nearly the whole of the Indian peninsula, little republics; supplied, owing to the regulations of caste, with artisans of nearly every craft, and almost independent of any foreign relations.’ 14 14 Irving: Theory and Practice of Caste .

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.