Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski - The Violoncello and Its History

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski - The Violoncello and Its History» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_home, music_dancing, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Violoncello and Its History

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Violoncello and Its History: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Violoncello and Its History»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Violoncello and Its History — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Violoncello and Its History», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In Judenkünig’s and Hans Gerle’s works are found the accompanying illustrations of stringed instruments provided with a bridge. Their identity is unmistakable, though they differ from each other in many peculiarities of form. Both instruments represent the so-called “big fiddle” 3 3 The “big fiddle” of the sixteenth century must not be confounded with the stringed instrument of that time, of which the pitch answered to our modern Contra-basso, and in Italy was already called “Violone,” as appears from Laufranco’s “Scintille,” 1533.

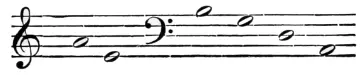

or “Basso di Viola.” The tuning was that of the lute, which, as an older stringed instrument, served in this respect as its model. Only in regard to the pitch did any difference exist. Judenkünig makes it thus:—

Hans Gerle, on the contrary, writes it thus:—

Here the pitch of the second is a fifth lower than the first. Judenkünig’s pitch represents the tenor and that of Gerle the bass. Agricola says in his “Musica instrumentalis,” regarding the height of pitch for the lute:

“Zeuch die Quintsait so hoch du magst

Das sie nicht reist wenn du sie schlagst.”

(Draw up the fifth string as high as you may,

That it may not be broken when on it you play.)

And in Hans Neusiedler’s Lute-book (1535) it is said: “He who wishes to learn how to tune the lute, let him draw up the Quint string, not too high, and not too low, a medium height, as much as the strings will bear.” Similar instructions are to be found in Gerle’s “Musica Teutsch.”

The capability of tension of the Quint string was consequently the guide for the pitch in tuning the lute—beyond this there was as yet no normal pitch—and in stringed instruments it was in every case so maintained. In playing with wind instruments the stringed instruments had, therefore, to adapt the pitch to them.

The “great violins” were, in the first half of the sixteenth century at least, according to all appearance played in two ways. From the drawing in Judenkünig’s treatise, a mode of handling is seen which requires no further explanation. That the handling of the “great violin” represented by Judenkünig without any explanation is treated of as not exceptional appears also from the accompanying vignette of another publication of that period.

The bass viol performing with the two lutists represents the same position and manner of playing as the woodcut in Judenkünig’s treatise, with the sole difference that he is holding his instrument in the left hand, whereas the peg-box of the instrument, bent sharply backwards, of Judenkünig’s player rests on his shoulder. It is very evident that in both cases scarcely more could be executed than the simplest bass accompaniment. More, however, was eventually to be produced according to the treatment of the “great violin” prescribed by Gerle. He says regarding it: “When you have according to my instructions ‘beschriben’ (noted), 4 4 The word “beschriben” refers to the letters which, for the convenience of the player, it was the custom to mark for the fingers on the fingerboard.

tuned and drawn up the violin, and wish to begin playing, proceed thus: Take the neck of the instrument in the left hand and the bow in the right, sit down and press the viola between the legs, that you may not strike it with the bow, and take care when you play that you draw the bow directly and evenly over the strings neither too far from nor too near the bridge 5 5 The artist who drew the sketches of the instrument for Gerle’s “Musica Teutsch” has left out the bridge in the “great viola.” See page 2 .

on which the strings lie, and that you do not draw the bow over two strings at once, but only over that which is placed under the figuring in the Tablature, and this must be especially attended to.”

It appears, according to Gerle’s instructions, that the instrument of which he speaks was a so-called “Knee violin”—in Italian, “Viola da gamba.” It seems, however, that in the sixteenth century this description was not in common use. Hans Gerle, a native of Nuremberg, born about 1500, had already received important consideration during the first twenty years of the sixteenth century, not only as a skilful performer, but also as a maker of lutes and viols. Yet the making of these instruments, and especially of viols, had already been carried on at a much earlier period by others. The oldest fiddle or viola maker of whom we have any mention is a certain Kerlino, who, according to Fétis’s account, lived and worked in Brescia. It is most probable that he was a German, or at least of German extraction, for the name Kerl, in every kind of variation, both as a common and individual or family name, had been constantly in use among the German races. In the German dictionary 6 6 See the article “Kerl.”

of the Brothers Grimm are indicated the various forms of the name “Kerl”: Kerle, formerly Kärle; Kerls, Kerles, Kerlis, Kerli, Kerlin, Kerel, Kaerl, Kerdel, and Kirl. They are of German origin, and are derived from middle or low German, whereas the Anglo-Saxon equivalents are “Carl,” or “Ceorl.”

Originally the word “Kerl” (kerle), according to Grimm, was synonymous with “Mann” (man), and also with Ehemann (husband). But it was also used as a family or tribal name, as is proved from the names Jacob de Kerle (sixteenth century), Joh. Kaspar von Kerll (also written Kerl, Kherl, Cherle), born 1628, and Vitus Kerle (in the eighteenth century). 7 7 Also at the present time it is a family name. We need only mention G. H. Bruno Kerl, Professor of the Royal Berg Academy at Berlin.

Another form of “Kerl,” Kerlin, was, according to Grimm, used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Who can doubt then that the Brescian instrument maker Kerlino was of German origin? 8 8 Other authorities, however, say he was a Breton—Fétis, Casimir Colomb &c.—( Tr. )

He was, evidently, originally called Kerl or Kerlin, to which name was added by the Italians either the diminutive syllable “ino” or the vowel “o.” It cannot be of Italian origin, for the Italian has no “k.”

Fétis informs us that Kerlino must be considered as the founder of the school of Brescian viola makers which, as the oldest in Italy from the middle of the sixteenth century, attained such a great reputation, through Gaspar da Salò and his reputed pupil, Giov. Paolo Maggini. If what appears so extremely probable has any real foundation, to a German, or, at least, to a man of German extraction, must be justly conceded the merit of having, in a measure, been the originator of the art of Italian stringed instrument making which later on developed to the highest point.

Further, we learn from Fétis that in the year 1804 a Parisian violin maker, named Koliker, was in possession of a violin which had been previously described by the French writer on music, de la Borde, containing the inscription

and which originally had been a “Viola da braccio.” Doubtless this remarkable instrument exists at the present time. Fétis, who saw it himself, describes its quality of tone as “agreeably soft and faintly subdued.” Among the composers who wrote for the viola, we must mention Giov. Battista Bonometti, born at Bergamo about the end of the sixteenth century. In 1615 he caused to be published in Vienna a collection of trios for two violas and a bass.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Violoncello and Its History»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Violoncello and Its History» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Violoncello and Its History» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Edward Ellis - Adrift on the Pacific - A Boys [sic] Story of the Sea and its Perils](/books/753342/edward-ellis-adrift-on-the-pacific-a-boys-sic-s-thumb.webp)