Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski - The Violoncello and Its History

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski - The Violoncello and Its History» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_home, music_dancing, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Violoncello and Its History

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Violoncello and Its History: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Violoncello and Its History»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Violoncello and Its History — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Violoncello and Its History», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It is evident that the directions of Corrette have chiefly a mere historical importance, as the technique of the violoncello, after the appearance of his method, underwent substantial changes. His explanation concerning the finger positions of that period and the thumb position which in the higher parts of the fingerboard takes the place of a moveable nut, concerning the manipulation of the bow, and the considerations to be observed in exchanging the gamba for the violoncello have a special interest for us.

With regard to the first of these four points, we remark that the finger position adopted by Corrette for the diatonic scale on all the strings was, in the first two positions, 1, 2, and 4; in the “third position,” 1, 2, 3, 4; and in the “fourth,” 1, 2, and 3; after the latter position the fourth finger was as a rule no longer needed, for which Corrette adduces as a reason that it is too short to be made use of in the higher positions of the fingerboard; in case however it should be necessary to use it, the use of the left arm would be impeded. In exceptional cases, says Corrette in another part of his school, the fourth finger could be used in the “fourth position,” without altering the thumb position, for the B flat and B on the A string, for the E flat on the D string, for the A flat on the G string, and for the D flat on the C string. The finger positions were then, in the first half and about the middle of the last century, somewhat different in the diatonic scale of the violoncello than they were later on. It is especially to be remarked that the E and the B were touched with the second finger upon the two lower strings, though the notes marked were far more convenient for the third finger, which very shortly took the place of the second.

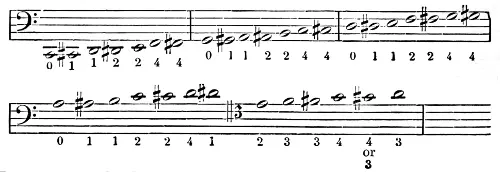

As to the exclusion of the fourth finger, when playing with the thumb position, no proof is needed to show the reason was that it gave an awkward manner of holding the left hand. The finger positions for the chromatic scale still more widely differed from the fingering employed later, as the following scale shows—

It very nearly happened, that as early as the seventeenth century when a stringed instrument was so much desired as a standard one for the violoncello, that the violin mode of fingering was adopted for the former, which according to the foregoing remarks really was the case, with the exception of the use of the third finger. It had however been overlooked that the cello, on account of its much larger dimensions, demanded an entirely different method of fingering. The regulation of this important point, which offered peculiar difficulties, occupied cellists up to the beginning of our century. In some measure the fingering which Corrette teaches for descending intervals of a second from the higher to the lower tones is unavoidable. He gives the two following examples—

He gave the preference to the second example.

The almost total exclusion of the fourth finger caused a very great restriction in playing with the thumb position. But when Corrette wrote his work this limitation would hardly have been felt, as the higher parts of the fingerboard were little, and, only in exceptional cases, used by cello players and composers. Corrette mentions, as the highest tone, the one-lined B. Caporale and Pasqualini do not go beyond this note in their sonatas, already mentioned, excepting in one instance, when Caporale casually uses the two-lined C. It appears that, with many cellists, in place of the thumb the first finger was made use of in the higher positions as a support, for Corrette remarks concerning his method: “If the first finger is used instead of the thumb the fourth finger must necessarily be made use of; it is, however, on account of its shortness, really useless in the upper ‘positions.’” To beginners Corrette recommended the attempt then in vogue—but a little later combated by Leopold Mozart in his violin school 66—to introduce marks on the fingerboard indicating the intervals in order to learn to play clearly in tune. For gamba players who, following the spirit of the time, gave up their instrument and turned to the violoncello, which was rapidly coming into use, this means of assistance had a certain value, accustomed as they were to the frets of the gamba fingerboard, for the finger positions of both instruments differ considerably from one another, as appears from the comparison given below by Corrette.

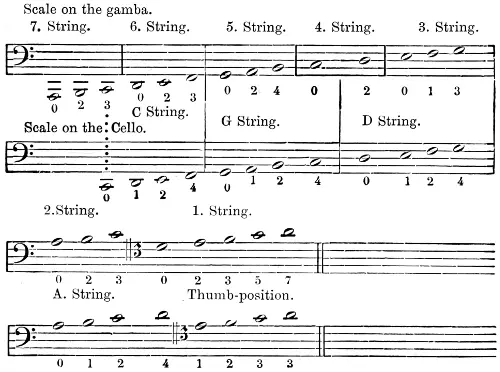

Scale on the gamba.

7. String. 6. String. 5. String. 4. String. 3. String. 2. String. 1. String.

Scale on the Cello.

C String. G String. D String. A String. Thumb-position.

The figures placed under the gamba scale relate to the frets which are to be attended to by the player, while those of the cello scale are the finger positions to be used.

The lower C, which the string itself forms on the cello, had on the gamba to be touched at the third fret; the succeeding D on the gamba was the open string, while on the cello it was to be touched with the first finger, and so on.

The four highest tones, e , f , g , a , fell in the gamba on the 2nd, 3rd, 5th, and 7th frets, whereas, according to Corrette’s account, those in the cello required the use of the thumb position. It is plain that the gamba players who took up the violoncello had to adopt an entirely different system of fingering.

To a certain extent the handling of the bow presented difficulties to those who exchanged the gamba for the violoncello. The former instrument, on account of the flatness of the bridge, did not allow of an energetic use of the bow. From the violoncello, on the contrary, a powerful tone must be brought out, which had to be learnt by gamba players. Besides, they had also to accustom themselves to other strokes of the bow for the cello. What was played by the latter instrument with a down stroke, was played by an upward one on the gamba, and the reverse.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

1

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the name “Geige” violin, then in ordinary use, must not be confounded with the violin of our time. This term was not applied to the more modern instrument until later.

2

A more detailed account of the above stringed instruments and their precursors is contained in my work, “The Violin and its Masters,” Second Edition (Leipsic: Breitkopf and Härtel), and “History of Instrumental Music in the Sixteenth Century” (Berlin: Brachvogel and Ranft), therefore a repetition of what is there said is unnecessary.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Violoncello and Its History»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Violoncello and Its History» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Violoncello and Its History» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Edward Ellis - Adrift on the Pacific - A Boys [sic] Story of the Sea and its Perils](/books/753342/edward-ellis-adrift-on-the-pacific-a-boys-sic-s-thumb.webp)