John Vinycomb - Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Vinycomb - Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_home, visual_arts, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Cloud Symbol of the “Sky” or “Air.”—Artists of the Mediæval and Renaissance periods, following classical authority, employed the cloud symbol of the sky or air in their allegories and sacred pictures of divine persons, saints, and martyrs, to denote their divine or celestial condition, as distinguished from beings “of the earth—earthy.” The adoption of the little cloud underneath the feet, when the figure is not represented flying, naturally suggested itself as the most fitting emblem for a support, and avoided the apparent incongruity of beings in material human shape standing upon nothing . The suggestion of the aerial support here entirely obviates any thought of the outrage on the laws of gravity.

Another distinguishing attribute is the Nimbus—an emblem of divine power and glory—placed behind or over the head. The crown is an insignia of civil power borne by the laity; the nimbus is ecclesiastical and religious. The pagans were familiar with the use of the nimbus, which appears upon the coins of some of the Roman Emperors. It was widely adopted by the Early Christian artists, and up till the fifteenth century was represented as a circular disc or plate behind the head, of gold or of various colours, and, according to the shape and ornamentation of the nimbus, the elevation or the divine degree of the person was denoted. It was displayed behind the heads of the Persons of the Trinity and of angels. It is also worn as a mark of honour and distinction by saints and martyrs. At a later period, when the traditions of early art were to some extent laid aside, i.e. , from the fifteenth century until towards the end of the seventeenth century, as M. Dideron informs us, a simple unadorned ring, termed a “circle of glory,” “takes the place of the nimbus and is represented as hovering over the head. It became thus idealised and transparent, showing an outer circle only; the field or disc is altogether omitted or suppressed, being drawn in perspective and formed by a simple thread of light as in the Disputer of Raphael. Sometimes it is only an uncertain wavering line resembling a circle of light. On the other hand, the circular line often disappears as if it were unworthy to enclose the divine light emanating from the head. It is a shadow of flame, circular in form but not permitting itself to be circumscribed.”

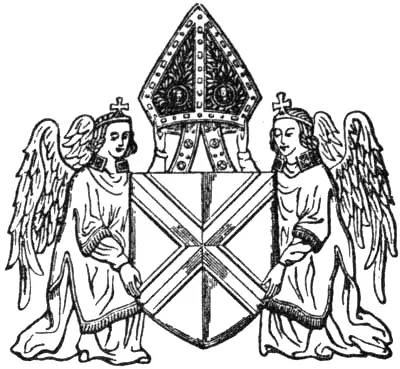

Angel Supporter.

Although the forms of angels are of such frequent occurrence in Mediæval Art they seem to abound more especially in the fifteenth century. Angels are seen in every possible combination, with ecclesiastical and domestic architecture, and form the subject of many allusions in heraldry. They are frequently used as supporters.

Charles Boutell, M.A., “English Heraldry,” p. 247, says, regarding angels used as supporters to the armorial shield: “The introduction of angelic figures which might have the appearance of acting as ‘guardian angels’ in their care of shields of arms, was in accordance with the feelings of the early days of English heraldry; and, while it took a part in leading the way to the systematic use of regular supporters, it served to show the high esteem and honour in which armorial insignia were held by our ancestors in those ages.” And reference is made to examples sculptured in the noble timber roof of Westminster Hall and elsewhere. As an example we give the shield of arms of the Abbey of St. Albans.

Kneeling Angel Supporter.

Figures of angels holding shields of arms, each figure having a shield in front of its breast, are frequently sculptured in Gothic churches. They appear on seals, as on that of Henry of Lancaster about 1350, which has the figure of an angel on each side of it. The shield of Richard II. at Westminster Hall, bearing the arms of France ancient and England quarterly, is supported by angels, which, if not rather ornamental than heraldic, were possibly intended to denote his claim to the crown of France, being the supporters of the Royal arms of that kingdom. Upon his Great Seal other supporters are used. There are also instances of the shield of Henry VI. being supported by angels, but they are by some authorities considered as purely religious symbols rather than heraldic.

Arms of the Abbey of St. Albans.

The supporters of the King of France were two angels standing on clouds, all proper, vested with taberts of the arms, the dexter France , the sinister Navarre , each holding a banner of the same arms affixed to a tilting-spear, and the cri de guerre or motto, “Mont-joye et St. Denis.” The shield bears the impaled arms of France and Navarre with several orders of knighthood, helmet, mantling and other accessories, all with a pavilion mantle.

Although Francis II., Charles IX., Henry III. and IV. and Louis XIII. had special supporters of their arms, yet they did not exclude the two angels of Charles VI., which were considered as the ordinary supporters of the kingdom of France. Louis XIV., Louis XV. and Louis XVI. never used any others.

Verstegan quaintly says that Egbert was “chiefly moved” to call his kingdom England “in respect of Pope Gregory changing the name of Engelisce into Angellyke,” and this “may have moved our kings upon their best gold coins to set the image of an angel.” 4 4 “Restit. of Decayed Intell. in Antiq.” p. 147.

“… Shake the bags

Of hoarding abbots; their imprisoned angels

Set them at liberty.”

The gold coin was named from the fact that on one side of it was a representation of the archangel in conflict with the dragon (Rev. xii. 7). The reverse had a ship. It was introduced into England by Edward IV. in 1456. Between his reign and that of Charles I. it varied in value from 6 s. 8 d. to 10 s.

Cherubim and Seraphim in Heraldry

“ On cherubim and seraphim

Full royally he rode. ”

“ What, always dreaming over heavenly things,

Like angel heads in stone wish pigeon wings .”

Cherubs’ Heads.

In heraldry A Cherub (plural Cherubim) is always represented as the head of an infant between a pair of wings, usually termed a “cherub’s head.”

A Seraph’s Head.

A Seraph (plural Seraphim), in like manner, is always depicted as the head of a child, but with three pairs of wings; the two uppermost and the two lowermost are contrarily crossed, or in saltire; the two middlemost are displayed.

Clavering , of Callaby Castle, Northumberland, bears for crest a cherub’s head with wings erect. Motto: cœlos volens.

On funereal achievements, setting forth the rank and circumstance of the deceased, it is usual to place over the lozenge-shaped shield containing arms of a woman, whether spinster, wife, or widow, a cherub’s head, and knots or bows of ribbon in place of crests, helmets, or its mantlings, which, according to heraldic law, cannot be borne by any woman, sovereign princesses only excepted.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Fictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.