Various - The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Various - The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, periodic, foreign_edu, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

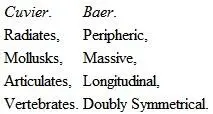

But it is not my object to give all the classifications of different authors here, and I will therefore pass over many noted ones, as those of Burmeister, Milne, Edwards, Siebold and Stannius, Owen, Leuckart, Vogt, Van Beneden, and others, and proceed to give some account of one investigator who did as much for the progress of Zoölogy as Cuvier, though he is comparatively little known among us. Karl Ernst von Baer proposed a classification based, like Cuvier’s, upon plan; but he recognized what Cuvier failed to perceive,—namely, the importance of distinguishing between type (by which he means exactly what Cuvier means by plan) and complication of structure,—in other words, between plan and the execution of the plan. He recognized four types, which correspond exactly to Cuvier’s four plans, though he calls them by different names. Let us compare them.

Though perhaps less felicitous, the names of Baer express the same ideas as those of Cuvier. By the Peripheric he signified those in which all the parts converge from the periphery or circumference of the animal to its centre. Cuvier only reverses this definition in his name of Radiates , signifying the animals in which all parts radiate from the centre to the circumference. By Massive , Baer indicated those animals in which the structure is soft and concentrated, without a very distinct individualization of parts,—exactly the animals included by Cuvier under his name of Mollusks , or soft-bodied animals. In his selection of the epithet Longitudinal , Baer was less fortunate; for all animals have a longitudinal diameter, and this word was not, therefore, sufficiently special. Yet his Longitudinal type answers exactly to Cuvier’s Articulates ,—animals in which all parts are arranged in a succession of articulated joints along a longitudinal axis. Cuvier has expressed this jointed structure in the name Articulates ; whereas Baer, in his name of Longitudinal , referred only to the arrangement of joints in longitudinal succession, in a continuous string, as it were, one after another. For the Doubly Symmetrical type his name is the better of the two; for Cuvier’s name of Vertebrates alludes only to the backbone,—while Baer, who is an embryologist, signifies in his their mode of growth also. He knew what Cuvier did not know, that in its first formation the germ of the Vertebrate divides in two folds: one turning up above the backbone, to inclose all the sensitive Organs,—the spinal marrow, the organs of sense, all those organs by which life is expressed; the other turning down below the backbone, and inclosing all those organs by which life is maintained,—the organs of digestion, of respiration, of circulation, of reproduction, etc. So there is in this type not only an equal division of parts on either side, but also a division above and below, making thus a double symmetry in the plan, expressed by Baer in the name he gave it. Baer was perfectly original in his conception of these four types, for his paper was published in the very same year with that of Cuvier. But even in Germany, his native land, his ideas were not fully appreciated: strange that it should be so,—for, had his countrymen recognized his genius, they might have claimed him as the compeer of the great French naturalist.

Baer also founded the science of Embryology, under the guidance of his teacher, Dollinger. His researches in this direction showed him that animals were not only built on four plans, but that they grew according to four modes of development. The Vertebrate arises from the egg differently from the Articulate,—the Articulate differently from the Mollusk,—the Mollusk differently from the Radiate. Cuvier only showed us the four plans as they exist in the adult; Baer went a step farther, and showed us the four plans in the process of formation. But his greatest scientific achievement is perhaps the discovery that all animals originate in eggs, and that all these eggs are at first identical in substance and structure. The wonderful and untiring research condensed into this simple statement, that all animals arise from eggs and that all those eggs are identical in the beginning, may well excite our admiration. This egg consists of an outer envelope, the vitelline membrane, containing a fluid more or less dense, the yolk; within this is a second envelope, the so-called germinative vesicle, containing a somewhat different and more transparent fluid, and in the fluid of this second envelope float one or more so-called germinative specks. At this stage of their growth all eggs are microsopically small, yet each one has such tenacity of its individual principle of life that no egg was ever known to swerve from the pattern of the parent animal that gave it birth.

III

From the time that Linnæus showed us the necessity of a scientific system as a framework for the arrangement of scientific facts in Natural History, the number of divisions adopted by zoölogists and botanists increased steadily. Not only were families, orders, and classes added to genera and species, but these were further multiplied by subdivisions of the different groups. But as the number of divisions increased, they lost in precise meaning, and it became more and more doubtful how far they were true to Nature. Moreover, these divisions were not taken in the same sense by all naturalists: what were called families by some were called orders by others, while the orders of some were the classes of others, till it began to be doubted whether these scientific systems had any foundation in Nature, or signified anything more than that it had pleased Linnæus, for instance, to call certain groups of animals by one name, while Cuvier had chosen to call them by another.

These divisions are, first, the most comprehensive groups, the primary divisions, called branches by some, types by others, and divided by some naturalists into so-called sub-types, meaning only a more limited circumscription of the same kind of group; next we have classes, and these also have been divided into sub-classes, then orders and sub-orders, families, sub-families, and tribes; then genera, species, and varieties. With reference to the question, whether these groups really exist in Nature or are merely the expression of individual theories and opinions, it is worth while to study the works of the early naturalists, in order to trace the natural process by which scientific classification has been reached; for in this, as in other departments of learning, practice has always preceded theory. We do the thing before we understand why we do it: speech precedes grammar, reason precedes logic; and so a division of animals into groups, upon an instinctive perception of their differences, has preceded all our scientific creeds and doctrines. Let us, therefore, proceed to examine the meaning of these names as adopted by naturalists.

When Cuvier proposed his four primary divisions of the animal kingdom, he added his argument for their adoption,— because , he said, they are constructed on four different plans. All the progress in our science since his time confirms this result; and I shall attempt to show that there are really four, and only four, such structural ideas at the foundation of the animal kingdom, and that all animals are included under one or another of them. But it does not follow, that, because we have arrived at a sound principle, we are therefore unerring in our practice. From ignorance we may misplace animals, and include them under the wrong division. This is a mistake, however, which a better insight into their organization rectifies; and experience constantly proves, that, whenever the structure of an animal is perfectly understood, there is no hesitation as to the head under which it belongs. We may consequently test the merits of these four primary groups on the evidence furnished by investigation. It has already been seen that these plans may be presented in the most abstract manner without any reference to special animals. Radiation expresses in one word the idea on which the lowest of these types is based. In Radiates we have no prominent bilateral symmetry, as in all other animals, but an all-sided symmetry, in which there is no right and left, no anterior and posterior extremity, no above and below. They are spheroidal bodies; yet, though many of them remind us of a sphere, they are by no means to be compared to a mathematical sphere, but rather to an organic sphere, so loaded with life, as it were, as to produce an infinite variety of radiate symmetry. The whole organization is arranged around a centre toward which all the parts converge, or, in a reverse sense, from which all the parts radiate. In Mollusks there is a longitudinal axis and a bilateral symmetry; but the longitudinal axis in these soft concentrated bodies is not very prominent; and though the two ends of this axis are distinct from each other, the difference is not so marked that we can say at once, for all of them, which is the anterior and which the posterior extremity. In this type, right and left have the preponderance over the other diameters of the body. The sides are the prominent parts,—they are charged with the important organs, loaded with those peculiarities of the structure that give it character. The Oyster is a good instance of this, with its double valve, so swollen on one side, so flat on the other. There is an unconscious recognition of this in the arrangement of all collections of Mollusks; for, though the collectors do not put up their specimens with any intention of illustrating this peculiarity, they instinctively give them the position best calculated to display their distinctive characteristics, and to accomplish this they necessarily place them in such a manner as to show the sides. In Articulates there is also a longitudinal axis of the body and a bilateral symmetry in the arrangement of parts; the head and tail are marked, and the right and left sides are distinct. But the prominent tendency in this type is the development of the dorsal and ventral region; here above and below prevail over right and left. It is the back and the lower side that have the preponderance over any other part of the structure in Articulates. The body is divided from end to end by a succession of transverse constrictions, forming movable rings; but the character of the animal, its striking features, are always above or below, and especially developed on the back. Any collection of Insects or Crustacea is an evidence of this; being always instinctively arranged in such a manner as to show the predominant features, they uniformly exhibit the back of the animal. The profile view of an Articulate has no significance; whereas in a Mollusk, on the contrary, the profile view is the most illustrative of the structural character. In the highest division, the Vertebrates , so characteristically called by Baer the Doubly Symmetrical type, a solid column runs through the body with an arch above and an arch below, thus forming a double internal cavity. In this type, the head is the prominent feature; it is, as it were, the loaded end of the longitudinal axis, so charged with vitality as to form an intelligent brain, and rising in man to such predominance as to command and control the whole organism. The structure is arranged above and below this axis, the upper cavity containing all the sensitive organs, and the lower cavity containing all those by which life is maintained.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.