William Noyes - Handwork in Wood

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Noyes - Handwork in Wood» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_home, Хобби и ремесла, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Handwork in Wood

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Handwork in Wood: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Handwork in Wood»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Handwork in Wood — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Handwork in Wood», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There are several methods of measuring lumber. The general rule is to multiply the length in feet by the width and thickness in inches and divide by 12, thus: 1" × 6" × 15' ÷ 12 = 7½ feet. The use of the Essex board-measure and the Lumberman's board-measure are described in Chapter 4, pp. 109and 111.

References 5

seasoning.

For. Bull. , No, 41, pp. 5-12, von Schrenk.

Dunlap, Wood Craft , 6: 133, Feb. '07.

For. Circ. No. 40, pp. 10-16, Herty.

Barter, pp. 39-53.

Boulger, pp. 66-70, 80-88.

Wood Craft , 6: 31, Nov. '06.

For. Circ. No. 139.

Agric. Yr. Bk. , 1905, pp. 455-464.

measuring.

Sickels, pp. 22, 29.

Goss, p. 12.

Building Trades Pocketbook , pp. 335, 349, 357.

Tate, p. 21.

Chapter IV.

WOOD HAND TOOLS

The hand tools in common use in woodworking shops may, for convenience, be divided into the following classes: 1, Cutting; 2, Boring; 3, Chopping; 4, Scraping; 5, Pounding; 6, Holding; 7, Measuring and Marking; 8, Sharpening; 9, Cleaning.

The most primitive as well as the simplest of all tools for the dividing of wood into parts, is the wedge. The wedge does not even cut the wood, but only crushes enough of it with its edge to allow its main body to split the wood apart. As soon as the split has begun, the edge of the wedge serves no further purpose, but the sides bear against the split surfaces of the wood. The split runs ahead of the wedge as it is driven along until the piece is divided.

It was by means of the wedge that primitive people obtained slabs of wood, and the great change from primitive to civilized methods in manipulating wood consists in the substitution of cutting for splitting, of edge tools for the wedge. The wedge follows the grain of the wood, but the edge tool can follow a line determined by the worker. The edge is a refinement and improvement upon the wedge and enables the worker to be somewhat independent of the natural grain of the wood.

In general, it may be said that the function of all cutting tools is to separate one portion of material from another along a definite path. All such tools act, first, by the keen edge dividing the material into two parts; second, by the wedge or the blade forcing these two portions apart. If a true continuous cut is to be made, both of these actions must occur together. The edge must be sharp enough to enter between the small particles of material, cutting without bruising them, and the blade of the tool must constantly force apart the two portions in order that the cutting action of the edge may continue.

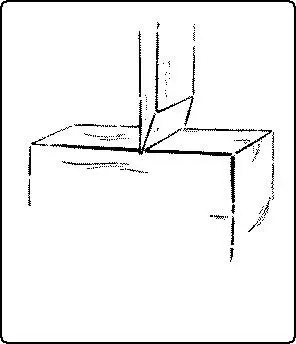

The action of an ax in splitting wood is not a true cut, for only the second process is taking place, Fig. 59. The split which opens in front of the cutting edge anticipates its cutting and therefore the surfaces of the opening are rough and torn.

Fig. 59. Wedge Action.

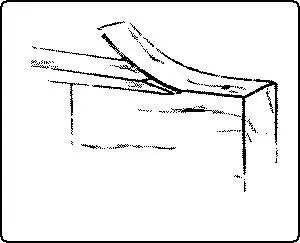

Fig. 60. Edge Action.

When a knife or chisel is pressed into a piece of wood at right angles to the grain, and at some distance from the end of the wood, as in Fig. 60, a continuous cutting action is prevented, because soon the blade cannot force apart the sides of the cut made by the advancing edge, and the knife is brought to rest. In this case, it is practically only the first action which has taken place.

Both the actions, the cutting and the splitting, must take place together to produce a true continuous cut. The edge must always be in contact with the solid material, and the blade must always be pushing aside the portions which have been cut. This can happen only when the material on one side of the blade is thin enough and weak enough to be readily bent out of the way without opening a split in front of the cutting edge. This cutting action may take place either along the grain, Fig. 61, or across it, Fig. 62.

The bending aside of the shaving will require less force the smaller the taper of the wedge. On the other hand, the wedge must be strong enough to sustain the bending resistance and also to support the cutting edge. In other words, the more acute the cutting edge, the easier the work, and hence the wedge is made as thin as is consistent with strength. This varies all the way from hollow ground razors to cold-chisels. For soft wood, the cutting angle (or bevel, or bezel) of chisels, gouges and plane-irons, is small, even as low as 20°; for hard wood, it must be greater. For metals, it varies from 54° for wrought iron to 66° for gun metal.

Fig. 61. Edge and Wedge Action With the Grain.

Fig. 62. Edge and Wedge Action Across the Grain.

Ordinarily a cutting tool should be so applied that the face nearest the material lies as nearly as possible in the direction of the cut desired, sufficient clearance being necessary to insure contact of the actual edge.

There are two methods of using edge tools: one, the chisel or straight cut, by direct pressure; the other, the knife or sliding cut.

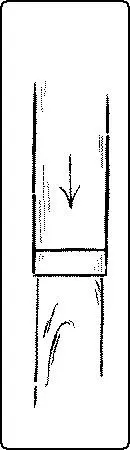

The straight cut, Fig. 63, takes place when the tool is moved into the material at right angles to the cutting edge. Examples are: the action of metalworking tools and planing machines, rip-sawing, turning, planing (when the plane is held parallel to the edge of the board being planed), and chiseling, when the chisel is pushed directly in line with its length.

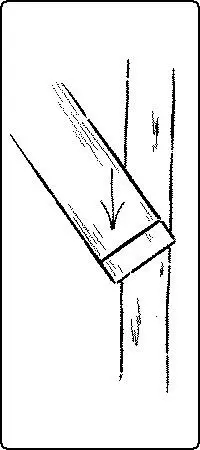

The knife or sliding cut, Fig. 64, takes place when the tool is moved forward obliquely to its cutting edge, either along or across the grain. It is well illustrated in cutting soft materials, such as bread, meat, rubber, cork, etc. It is an advantage in delicate chiseling and gouging. That this sliding action is easier than the straight pressure can easily be proved with a penknife on thin wood, or by planing with the plane held at an angle to, rather than in line with, the direction of the planing motion. The edge of the cutter then slides into the material. The reason why the sliding cut is easier, is partly because the angle of the bevel with the wood is reduced by holding the tool obliquely, and partly because even the sharpest cutting edge is notched with very fine teeth all along its edge so that in the sliding cut it acts like a saw. In an auger-bit, both methods of cutting take place at once. The scoring nib cuts with a sliding cut, while the cutting lip is thrust directly into the wood.

Fig. 63. Straight Cut.

Fig. 64. Sliding Cut.

The chisel and the knife, one with the edge on the end, and the other with the edge on the side, are the original forms of all modern cutting tools.

The chisel was at first only a chipped stone, then it came to be a ground stone, later it was made of bronze, and still later of iron, and now it is made of steel. In its early form it is known by paleontologists as a celt, and at first had no handle, but later developed into the ax and adze for chopping and hewing, and the chisel for cuts made by driving and paring. It is quite likely that the celt itself was simply a development of the wedge.

In the modern chisel, all the grinding is done on one side. This constitutes the essential feature of the chisel, namely, that the back of the blade is kept perfectly flat and the face is ground to a bevel. Blades vary in width from 1⁄16 inch to 2 inches. Next to the blade on the end of which is the cutting edge, is the shank, Fig. 65. Next, as in socketed chisels, there is the socket to receive the handle, or, in tanged chisels, a shoulder and four-sided tang which is driven into the handle, which is bound at its lower end by a ferrule. The handle is usually made of apple wood.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Handwork in Wood»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Handwork in Wood» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Handwork in Wood» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.