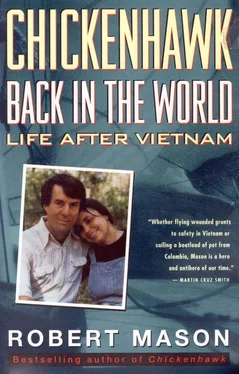

Robert Mason - Chickenhawk - Back in the World - Life After Vietnam

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Mason - Chickenhawk - Back in the World - Life After Vietnam» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: BookBaby, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam

- Автор:

- Издательство:BookBaby

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

During the break, I met the other American writers. I told Philip Caputo that A Rumor of War was partly responsible for me writing my book. He said he liked Chickenhawk . I told Tim O’Brien how much his first book, If I Die in a Combat Zone , influenced me, made me realize I, too, had something to say. I also told him I really enjoyed Going After Cacciatio . He was used to that, having won the National Book Award for it.

After the break, we went back to the attic and talked about the writing business. The Vietnamese were fascinated by the fact that American writers seemed to make so much money. They wanted to know how much money we made on our books. Caputo and O’Brien weren’t at this meeting, so I volunteered that I had made nearly a half million dollars so far on my book. They had the interpreter repeat this several times to make sure they were hearing right. I understood what the problem was when Le Luu, the author of the number-one bestselling novel in Vietnam, said that he had made enough money on his book to buy a new German bicycle. I felt embarrassed.

As we were leaving, Sang reminded me about our interview the next day. He was starving for authentic details from the other side. I shrugged. “I’ll be here.”

When I got to Kevin Bowen’s house the next morning, the Vietnamese were having a kind of soup they called pho for breakfast. While they slurped bowls of noodles and fish, I sat and drank coffee with the interpreter, Thong, whom I found fascinating. He was not a former enemy; he was not a threat to me. He was twenty-three, educated entirely in Vietnam. His English was beautiful. I asked him how he liked America. He said he wasn’t allowed to leave New York City (this trip was a special exception), where the Vietnamese mission was located, but he liked the city, had American friends there.

Bowen said that he had to go to the university, and left. In a few minutes I realized that there was no one in the house except me and two Vietnamese: Ha Huy Thong, the interpreter from Hanoi, and Nguyen Quang Sang, the tunnel-rat Viet Cong who’d shot down a lot of helicopters.

We sat at Bowen’s kitchen table. The table was wood, old, pleasantly worn. Sang sat across from me and switched on his Sony tape recorder, flipped open a notebook. Thong sat between us.

Thong told me that Sang had gotten a lot of criticism of his movie when some Americans had seen it. For one thing, Thong said, Sang showed the American pilots returning home to their base and partying with whiskey drunk from champagne glasses. I laughed.

Sang looked at me seriously. I could see he was studying me, sizing me up. I suppose he was struck by our polarities as much as I. He spoke. Though what he said was incomprehensible to me, his voice was deep, authoritative. This was a warrior who, with others like him, had fought the mightiest country on earth and survived. Thong said, “How many helicopters were in your unit?”

I looked at Sang. He waited for the answer, pencil poised over a notepad. I looked up at the kitchen window and back at Sang. Morning light filtered across the old table. The ridges showing on the rustic, worn wood, the smell of Vietnamese food, the confident look on Sang’s face made me feel suddenly queer. It was like I’d been shot down, captured.

Name, rank, and serial number. That’s what came to mind. That’s crazy, I thought. It’s all public information now. I said, “Our battalion had four companies of about twenty ships each.”

Sang nodded, made a note.

“You called them ‘ships’?”

“Yes. It’s a general word for a craft, air or sea.”

Sang nodded. “And how many aviation battalions were in the First Cavalry?”

“We had two assault helicopter battalions of Hueys, a battalion of heavy-lift Chinook helicopters, and an independent group, the Ninth Air Cav. Altogether, the Cav had about four hundred helicopters.”

Sang nodded, scribbled. “What kind of food did you eat?”

“C-rations, mostly,” I said.

“The pilots did not eat better at their home bases?”

“Some did. We didn’t. The First Cavalry lived in the field. At our base at An Khe we were served canned food called B-rations.”

Sang nodded, spoke. Thong said, “He said he was lucky to get a fish head with his rice.”

Sang’s confidence, and now his professed Spartanism, irked me. “How many villagers did he kill to get the rice?”

Thong looked at me intently, shrugged, turned to Sang, and spoke. Sang’s face darkened. He shook his head and spoke, his voice angry.

Thong shrugged. “He says he never killed his own people. Only you.”

“Oh. The other Viet Cong killed the villagers,” I said.

Thong answered without translating. “Yes. It was unfortunate.”

That night, I shared billing with Wayne Karlin and Tim O’Brien at the Boston Public Library. Karlin read from Lost Armies ; I read a few passages from Chickenhawk , all having to do with the Vietnamese. O’Brien read outtakes from his forthcoming book, The Things They Carried .

It didn’t occur to me until later that night, in bed, that people must consider me to be an important writer, to have invited me to that reading. Imagine that.

The next day, David Hunt asked me if I’d return to Vietnam with the other writers, a reciprocal meeting with the Vietnamese writers. I said I would.

My mother was in the hospital while I wrote most of this book.

On August 29, 1990, Patience and Jack and I, along with my sister, Susan; her husband, Bruce; my nephew, Sean; and my niece, Bevan, took a boat out into the Gulf of Mexico and sprinkled her ashes on the waves. My father refused to come. None of her brothers or sisters attended or even came to see her in the hospital. There was no love in her family, a sad thing to see.

We drank a toast of dry martinis, a drink she asked for as she lay dying, unable to drink anything. I tossed a full glass, with olive, into the water for her.

My mother, despite having a heart condition most of her life, was an energetic woman. She grew up believing the woman’s place was in the home, but had worked as a grocery checkout clerk when we first moved to Florida in 1945. Once, when my parents were struggling to make ends meet, she suggested that she go to school and become a nurse, but my father refused to allow it. He believed he should be able to provide for us himself. From 1951 to 1958, my mother did physical work on the chicken farm my dad started west of Delray Beach. We had a hundred thousand chickens on this farm, and we—my mother and father, my sister and I—did most of the work. After my dad sold the farm in 1958, moved us to Delray Beach, and became a real-estate broker, they were sufficiently well off that she could become the ideal of her culture—the wife of a successful businessman. She fulfilled her role by keeping our house as neat as a museum display and giving a cocktail party almost every Friday night.

At the age of sixty-four, a disease called lupus, and the drugs used to treat it, destroyed one of her hip joints. After spending nearly a year in a wheelchair, she decided to have the operation for an artificial hip joint. She was frail; the operation nearly killed her.

She called one day, a few weeks after the operation, said to come over, she had a surprise. When we got there, I saw her standing in the living room wearing a brand-new dress, beaming. After a year in a wheelchair, it was a miracle.

Two days later, she suffered a blood clot in her arm and had to have another operation.

She came home for a week, then went back in for other complications. She never left. I see her standing in the living room, smiling, happy just to stand up. I see her in the hospital, withered, in pain, dying. I see a cardboard box of granular ashes and dust.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Chickenhawk: Back in the World - Life After Vietnam» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.