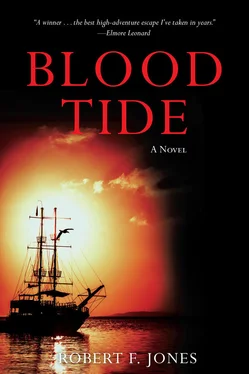

Robert Jones - Blood Tide

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Jones - Blood Tide» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blood Tide

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blood Tide: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blood Tide»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blood Tide — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blood Tide», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Miranda had just turned eighteen then. Her mother wanted her to go to San Diego State for a business degree, then come to work in the bank where she was now a rising star in the loan department. “Money is the lifeblood of the world,” her mother said. But Miranda’s lifeblood was the sea. She was legally an adult now, free to choose her own course in life. She signed up as a deckhand on a tuna clipper heading down the South American coast.

It was hard work on a cold sea. The captain, a former shipmate of her father’s, treated her no better or worse than he did the rest of the crew but saw to it that the men didn’t try to mess with her. She swabbed decks, polished brightwork, and mended rigging with the best of them, learned to gut hundred-pound yellowfin tuna with one slash of the knife. Often at night she left her shipmates in the fo’c’sle and climbed the rigging to sit shivering in the tuna tower, watching the moon on the distant snowcaps of the Andes. She could feel the whales blowing out there, the shoals of tuna rolling as they fed, and the bone-dry, far-off mountains. Fish scales whirled off her hands like snowflakes in the wind. She earned her sea legs on that cruise.

In Hawaii, later, she crewed on gypsy charter boats for a while, then signed on a racing yacht as a grinder. A girl on the winches was good public relations for the millionaire who owned the boat. She was strong—nearly six feet tall, as wide-shouldered as most men, with short-cropped black hair bleached at the ends by the sun, and big, hard hands and callused feet. In the tropic heat and rain her face and bare arms had tanned as dark as a Polynesian’s. Her eyes, though, were sea green and bright as coral water, with island flecks of brown in them. She had a hawklike profile thanks to a broken nose. Down near Viti Levu in the Fijis, during a transpacific race, a winch exploded on her one night, the boom came across at once, and she caught a glancing blow as she wrestled with the runaway sheet.

The accident left her jobless, in the clinic at Suva with a concussion, and with very little money. The racers sailed on. Down at the docks, once she’d healed, she met a skipper named Taka, a big, dark, grave man from Tongatapu who owned a trading schooner that worked regularly from Samoa down to New Zealand and back. She sailed with him for a year, working her way up to mate. It taught her more of the ways of the working sea, as opposed to the racing one, with all its glitz and glamour. Taka hauled pigs and chickens, copra and gas drums and diesel engines. His canvas sails weighed a ton compared with the light synthetic ones on the yachts. The schooner’s wooden hull demanded a lot of care. They holystoned her teak deck once a week with sand and firebricks and sluiced the planks with buckets of seawater until the sun bleached them bone white. They careened the schooner from time to time in shallow lagoons to scrape the barnacles from her hull and slap on antifouling paint to foil the shipworms. They rove new rigging, mended blown sails, fought a nonstop war against verdigris, termites, and cockroaches.

Topside, Miranda became adept with sextant and chronometer, charts and star tables, compass, dividers, and parallel rules. She learned to read the tropical sky and the sea in all their swirling complexities—tides, winds, currents, clouds, set and drift, haze and spindrift and rings around the moon; rocks and shoals, shifting on up through the color spectrum as the keel neared danger, from blue through green and yellow to hull-gutting brown. She learned to tell good holding ground from bad in any anchorage and the places where you had to settle for bad if you didn’t want to get eaten alive by sand fleas or mosquitoes. She learned to find a hurricane hole in a hurry when she needed one and, if she couldn’t, to ride out the storm at sea. That sort of lesson, once learned, she hoped she’d never have to repeat.

Along the way she saved her wages, and with them, finally, she bought a thirty-six-foot ketch from a broker in Auckland. The ketch was named Seamark . It was white-hulled and weatherly, fast on the wind. In her Miranda sailed the web of the central Pacific, from Tahiti and Mooréa on up to Hawaii, through the Tuamotus and the Fijis and Samoa, on across to the Marshalls and the Gilberts, once even as far as Rabaul. Where there were resorts she stopped for a while and earned her keep by taking tourists for day sails or picnics with maitais on deserted motus or for morning outings to dive over some safe reef. Where there were no resorts she hauled freight, as Taka had taught her to do.

Most of her crew and all of her mates, over the years, were island boys. She found them harder working, better sailors, and more fun than Americans or even Australians. She could learn from them—local languages, like the beche-de-mer of the Solomons, or pidgin, which changed almost island by island, or the dark, staccato French of Polynesia; the lore of shark gods and kahunas and the Great World-Builder, Maui, who yanked the islands one by one from the bottom of the endless sea with a bone fish-hook; and practical fishing as well, like how to bend a mullet or a flying fish to a long-shanked trolling hook of stainless steel so that it wouldn’t slide off; or the best way to cook pig in an umu , the oven dug into the earth and lined with hot stones and taro or plantain leaves in which island chefs steamed their suppers and, not so long ago, their enemies. That dish was called pua’a oa —long pig. The best parts of a human being, an old Tuamotuan mate of hers named Jean-Claude Marama had told her, were the buttocks and the soles of the feet. “ Vraiment ,” he said. “ Très agréable .”

“How do you know when they’re done right?” she’d asked him.

“When ze steam comes out from ze eyeballs.”

Some of the mates became good friends. There was Charlie Tehare from the Tubuais, who could free-dive sixty feet on one huge lungful of air and stay down three minutes to clear a fouled anchor or spear a supper of grouper; and Heinzelmann, the wisecracking Samoan from Apia who could strip, repair, and reassemble any engine known to man in a matter of minutes; and Effredio Pascal from Negros in the Philippines, who taught Miranda everything she wanted to know about sea crocodiles and knife fighting. Pascal was a short, wiry man covered with scars. Didn’t talk much except when he’d been drinking; then you couldn’t shut him up. He’d tell you all about the war and MacArthur and the Moro juramentados of the insurrection, who bound their testicles in wet leather so that when it dried and shrank, the pain would drive them on to commit murder and face death willingly, who when bayoneted would grab the rifle barrel and drive the steel deeper so as to get at the man at the other end. Drunk, Pascal would describe to her the Balbal, a giant flying squirrel from Palawan with the body of a man and long, curved claws with which he loved to rip the thatch from a nipa hut and, with his sticky, snakelike tongue, lick up the people sleeping within. When he’d gotten her all spooked and goose-pimply, he’d suddenly jump to his feet and stare at her with wide, mad eyes. “I’m Effredio!” he’d scream. Then, subsiding to his heels with a warm smile, he’d ask, “Are you effred-a me?” At times like that, she was.

Some of the mates she slept with, some not. It didn’t really matter. They were all good shipmates. All except the last, an American named Curten. She’d slowly been working her way back east by a series of charters that just happened to break in that direction—from the Marquesas to Pitcairn, then to Easter Island, then up to the Galápagos. Having come that far, she single-handed northward to Mexico, flush now from the earlier charters, to see what the coast had to offer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blood Tide»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blood Tide» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blood Tide» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.