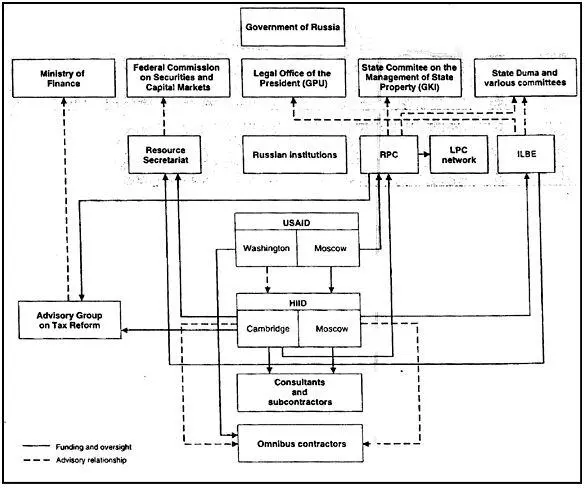

INSTITUTIONS, ORGANIZATIONS, COMMISSIONS

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TREASURY: a leading agency making U.S. policy toward Russia and Ukraine, which supported Anatoly Chubais and the Chubais Clan and HIID projects in both Russia and Ukraine.

NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL (NSC): a leading agency making U.S. policy toward Russia and Ukraine, which supported Anatoly Chubais and the Chubais Clan and HIID projects in both Russia and Ukraine.

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, OFFICE OF THE AID COORDINATOR: a leading body carrying out U.S. policy toward Russia and Ukraine, which supported Anatoly Chubais and the Chubais Clan and HIID projects in both Russia and Ukraine.

U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID): the U.S. government agency through which foreign aid flows.

GORE-CHERNOMYRDIN COMMISSION: a high-level, bilateral commission set up by U.S. Vice President Albert Gore and Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin; formally the US-Russia Joint Commission on Economic and Technological Cooperation after Chernomyrdin’s dismissal by Yeltsin, the commission has continued between Gore and the new prime ministers.

WORLD BANK: the development bank funding some projects in Russia run by Anatoly Chubais and members of the Chubais Clan.

HARVARD INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (HIID): Harvard University’s institute specializing in international development, founded in 1974 and slated for dissolution (and the integration of its projects into other university programs) in 2000, following allegations of mishandling of USAID funds.

HARVARD MANAGEMENT COMPANY (HMC): Harvard’s endowment fund, which has invested in Russia through Renaissance Capital’s Sputnik Fund since the early 1990s.

RUSSIAN PRIVATIZATION CENTER (RPC): a “private” organization set up in 1992 to further privatization and economic reform. The RPC was run by Chubais Clan members, substantially funded by USAID, and also received hundreds of millions of dollars in grant aid and credits from the United States, the governments of Germany, the United Kingdom, and Japan, the European Union, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and others.

INSTITUTE FOR LAW-BASED ECONOMY (ILBE): an HIID-created, U.S.-and World Bank–funded “private” organization run by the Harvard–Chubais coterie, which was set up to help develop a legal and regulatory framework for markets and evolved to entail drafting decrees for the Russian government.

STATE PROPERTY COMMITTEE (GKI): the Russian state’s privatization agency founded in 1991, which, under the leadership of Chubais Clan members, carried out the privatization of some 15,000 state enterprises.

FEDERAL SECURITIES COMMISSION: rough equivalent of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), known by some Americans as the “Russian SEC,” established by presidential decree and run by Chubais Clan member Dmitry Vasiliev.

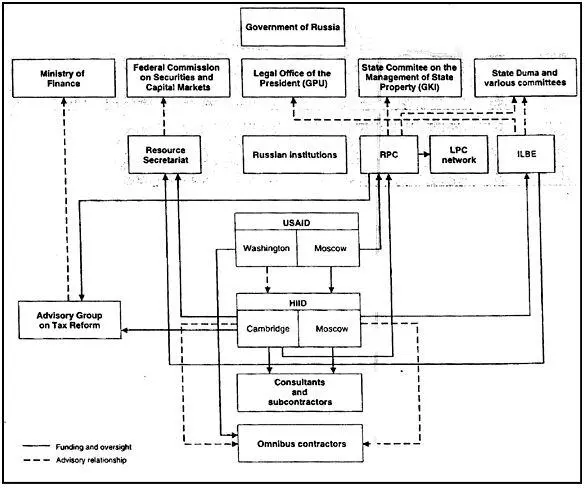

ORGANIZATIONAL PROFILE OF THE HARVARD INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

(AS OF JUNE 30, 1996)

Source: U.S. General Accounting Office, Foreign Assistance: Harvard Institute for International Development’s Work in Russia and Ukraine, Washington, D.C., GAO: National Security and Affairs Division, November 1996, p. 62.

Legend:

HIID= Harvard Institute for International Development

ILBE= Institute for Law-Based Economy

LPC= local privatization center

RPC= Russian Privatization Center

USAID= U.S. Agency for International Development

NOTES

INTRODUCTION

1. Interview with Grzegorz Kołodko, March 13, 1990.

2. This perspective is informed by a joint research proposal with David A. Kideckel, “Foreign Aid as Ideology and Culture: The Case of Transitional Eastern Europe,” submitted to (and funded by) the National Science Foundation, 1993.

3. Anthropologist Philip C. Parnell has conducted pioneering ethnography across levels and processes in the Philippines and Mexico. See Philip C. Parnell, “The Composite State: The Poor and the Nation in Manila,” Ethnography in Unstable Places, Carol Greenhouse, Elizabeth Mertz, and Kay Warren, eds., Duke University Press, forthcoming, and Escalating Disputes: Social Participation and Change in the Oaxacan Highlands, Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1989.

4. Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai provides an important treatment of processes of “globalization” from the angle of actors who are profoundly affected by global processes (Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

5. Because aid is seldom conceptualized as a process and interface between social systems, the problem is little examined in much of the theory on foreign assistance, which has been formulated mainly by non-anthropologists from donor societies. (See, for example, the following economists’ critiques of the economic development field: Benjamin Higgins [ A Path Less Travelled: A Development Economist’s Quest, National Centre for Development Studies 2, Australian National University, Canberra, 1989]; Tony Smith [“The Underdevelopment of Development Literature: The Case of Dependency Theory,” The State and Development, Atul Kohli, ed., Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986]; and Judith Tendler [ Inside Foreign Aid, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975].)

6. Anthropologist Michael Herzfeld has explored how the outcomes of nation-state policies are influenced by actors in semi-closed environments (Michael Herzfeld, A Place in History: Social and Monumental Time in a Cretan Town, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991).

7. See, for example, C. M. Hann ( Tazlar: A Village in Hungary, London, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1980; A Village Without Solidarity, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), David A. Kideckel (“The Socialist Transformation of Agriculture in a Romanian Commune, 1945-1962,” American Ethnologist vol. 9, no. 2, 1982, pp. 320-340; The Solitude of Collectivism: Romanian Villagers to the Revolution and Beyond, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993), Martha Lampland (The Object of Labor: Commodification in Socialist Hungary, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995), Carole Nagengast ( Reluctant Socialists, Rural Entrepreneurs: Class, Culture, and the Polish State, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991), Steven Sampson (“The Informal Sector in Eastern Europe,” Telos, no. 66, winter 1986, pp. 44-46), and Janine R. Wedel ( The Private Poland: An Anthropologist’s Look at Everyday Life, New York, NY: Facts on File, 1986; The Unplanned Society: Poland During and After Communism, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1992).

8. A. F. Robertson proposes that development agencies themselves are as worthy of study as the peasant groups with which anthropologists typically are concerned ( People and the State: An Anthropology of Planned Development, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1984). Michael Cernea, “Sociological Knowledge for Development Projects,” Conrad Kottak, “When People Don’t Come First,” and Norman Uphoff, “Fitting Projects to People,” suggest that development ideologies affect the implementation of development projects ( Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development, Michael M. Cernea, ed, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1985). Wolfgang Sachs et al discuss “knowledge as power” (ed., The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge and Power, London, United Kingdom, Zed Books, 1992) while Michael J. Watts analyzes the history of development and its language (“Development I: Power, Knowledge, Discursive Practice,” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 17, no. 2, 1993, pp. 257-272) and Arturo Escobar discusses its “invention” (“The Invention of Development,” Current History, vol. 98, no. 631, November 1999, pp. 382-386). Mark Hobart (ed., An Anthropological Critique of Development: The Growth of Ignorance, New York, NY: Routledge, 1993) establishes a relationship between development and the “growth of ignorance,” while R. D. Grillo and R.L. Stirrat (eds., Discourses of Development: Anthropological Perspectives, Oxford, United Kingdom: Berg, 1997) explore discourses of development and the relationships that arise between power, politics, and ideology in the practice of development.

Читать дальше