Today, as some Central Europeans match and even outdo their Western counterparts in extravagance and inattention to their neediest citizens, it is sometimes hard to remember the time when the excesses of the Marriott Brigade were universally perceived as offensive. This is not to say that all potential for antagonism toward “the West” has dissipated, especially not in regions and nations where large segments of the population perceive themselves as doing poorly. But the lines of polarization appear different now, because they are primarily between those who have become wealthy with the collapse of communism and those who have not. The same, however, cannot quite be said for Russia or Ukraine.

These lines are partly drawn between countries that are seen as viable candidates to join “the West”—that is, to join multistate economic and political organizations—and those that are not. The most important of these organizations in political, economic, and social terms is the European Union, composed, at this writing, of 15 states of Western and Southern Europe. Three new members—Austria, Finland, and Sweden—joined the EU in 1995, and since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Europeans have been weighing issues of expansion to the east. To become a member, each country must meet four EU-defined political conditions (establishing a rule of law, supporting democracy, recognizing human rights, and protecting minorities), and one economic condition (the creation of an internationally viable market economy). Ten Central and Eastern European countries have applied for EU membership. The European Commission, the central body of the EU headquartered in Brussels, selected the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia for negotiations in the first round.

The most important aspect of EU membership is the institutionalization of relations across a range of levels and domains, economic, political, and cultural. Because of its multifaceted nature, membership in the EU is regarded as much more significant than membership in other international and regional organizations.10 But it is important to keep in mind that memberships in international organizations are long-term relations and processes—as we have seen with the original EU members of Western Europe—and not ends in themselves. EU influences can help shape the relations and processes of its new members, but “joining the West” will not cause people to automatically forget history.

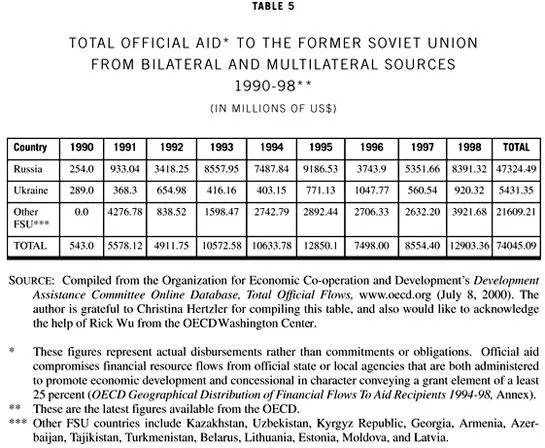

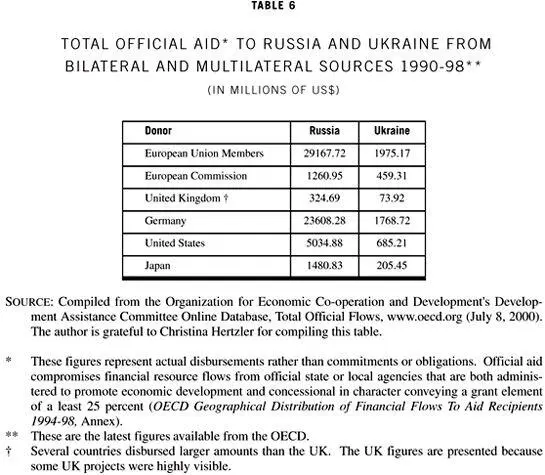

Just as the relationship between Easterner and Westerner is of paramount importance as the century closes, so is the relationship between Easterner and Easterner. This polarization is nowhere more in evidence than in Russia, where frustration and resentment toward the West may well linger. The Russian self-image of a down-at-the-heels superpower created the conditions for charges of Western interference—charges that were often linked to foreign aid. In Russia and Ukraine the perception of the West as a demon has lingered and even been reignited. In contrast to the Visegrád countries, where aid relations entailed uneasy contact but eventually resulted in some selective learning and working together, in Russia, aid resulted in adaptations detrimental to the West.

Whether as saint or demon, the West will continue to play an important role in Central and Eastern Europe’s emergence from communism. The lines of polarization between East and West now appear different because at least Central Europeans are increasingly claiming a place in European and international organizations and activities. The term “Marriott Brigade” no longer resonates so harshly for local people because, more and more, some local people have adopted—and even elaborated—the lifestyle characterized by the Brigade. Polish, Hungarian, and Czech consultants now represent the West as part of EU delegations in Romania and Ukraine, and many represent donor organizations as well. More often than not they are treated as partners, if not with deference. And that is what any aid efforts, in the future, should strive to create: cooperation with partners.

If nothing else, the story of aid to Central and Eastern Europe shows how consideration of relationships must be a significant part of any aid strategy. The issues the Central and Eastern European aid story has raised—the expectations, terms, and relationships through which the West connects with the East—will endure. The means of connecting with one’s foreign “partners” will continue to be crucial, and not only in situations where the West is sending aid or trying to help. Indeed, relationships are pivotal in diplomacy, international agreements, and business.

In recent years, development anthropologists have focused on the “discourses” of development. The Central and Eastern European aid story is rife with colorful metaphors of transition—of turning fish soup back into an aquarium, having a tooth pulled, or crossing a chasm. The fact that these metaphors were used not just to explain, but actually to justify, policies further confirms the importance of studying aid discourses.

The analysis of discourse also, critically, reveals power relations. The U.S. aid community talks about curtailing aid programs by “graduating” the recipient countries. “Graduation” implies that the pupils went to “our” school and succeeded to the extent that “we” assessed their readiness for graduation. At the very least, this view implies that “we” had more influence in most cases than we did; that “our help” was decisive. Clearly, a close look at the language of aid is warranted.

Finally, a return to the work of anthropologists in the powerful areas of social organization and political and economic links is called for in a major way—both to explain the effects of aid strategies and relations between donors and recipients, and, more important, to assess how aid affects relations on many levels in the recipient countries. It is only through a grounded, real-world focus on political, economic, and social relationships that we can understand the “chemical reactions” of the development encounter and make progress toward disentangling—and changing—the world system we know as development.

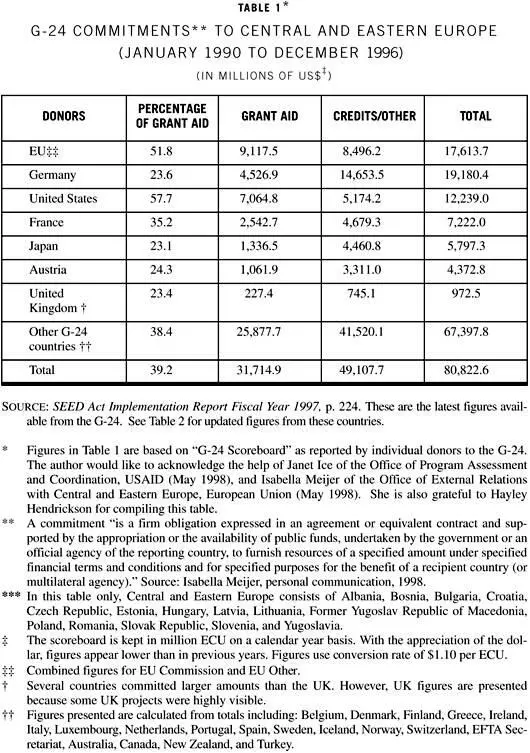

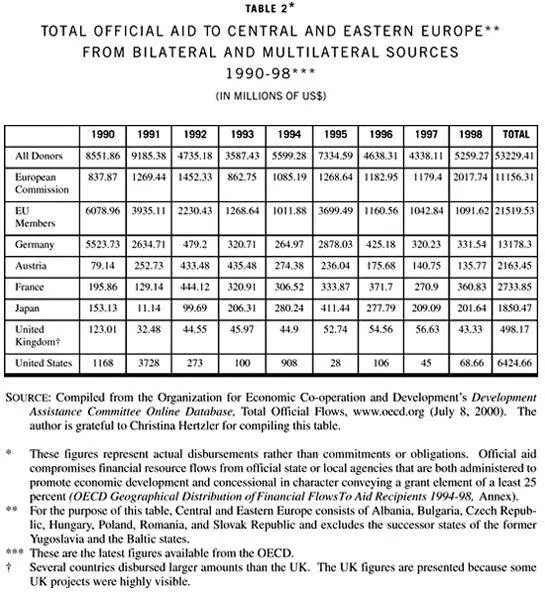

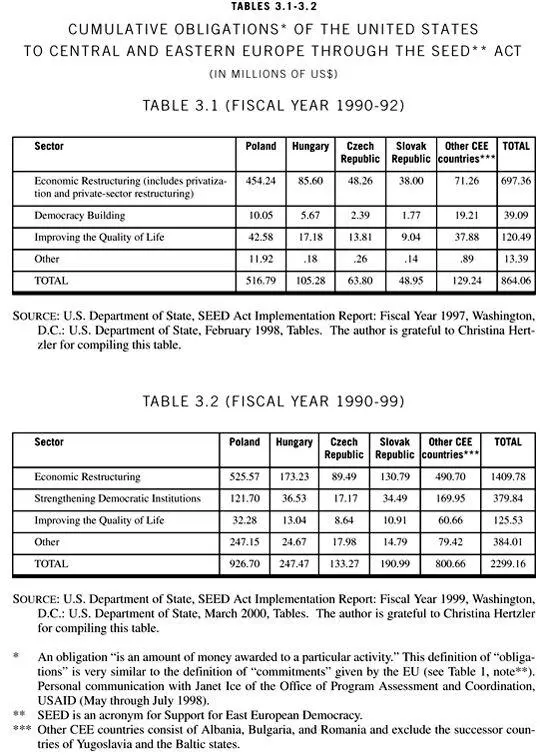

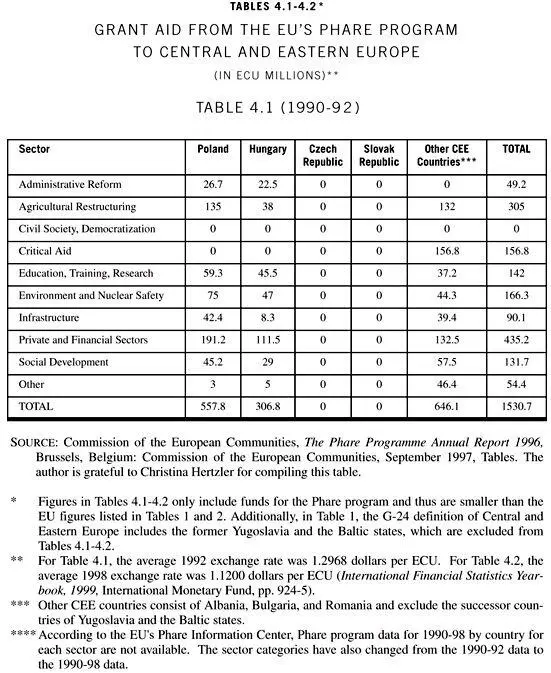

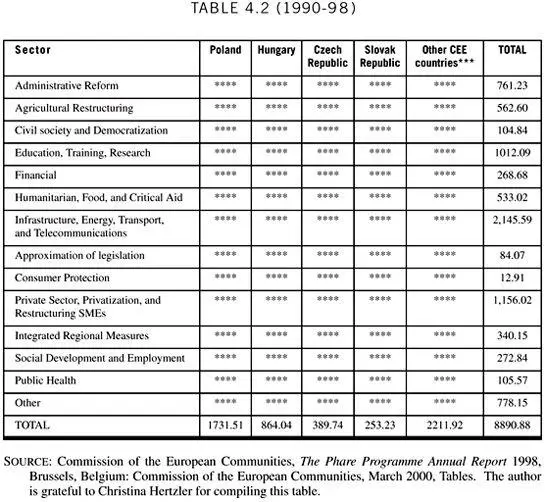

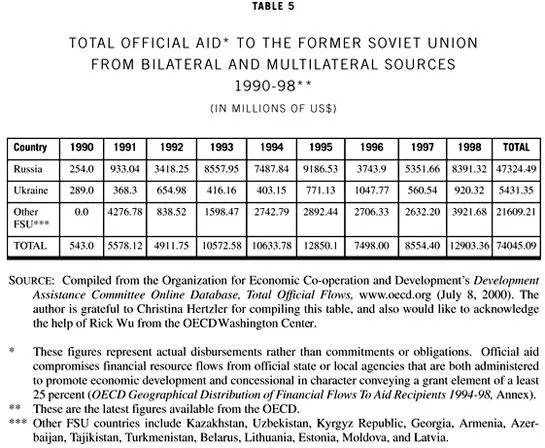

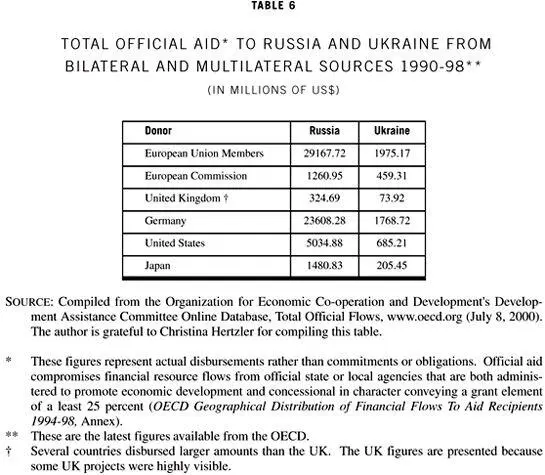

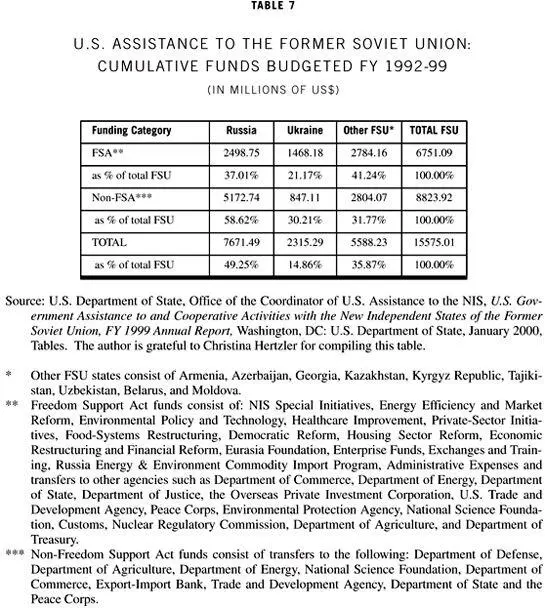

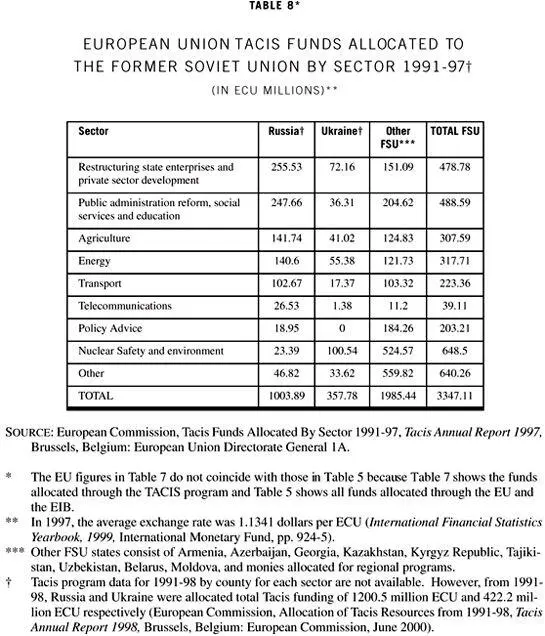

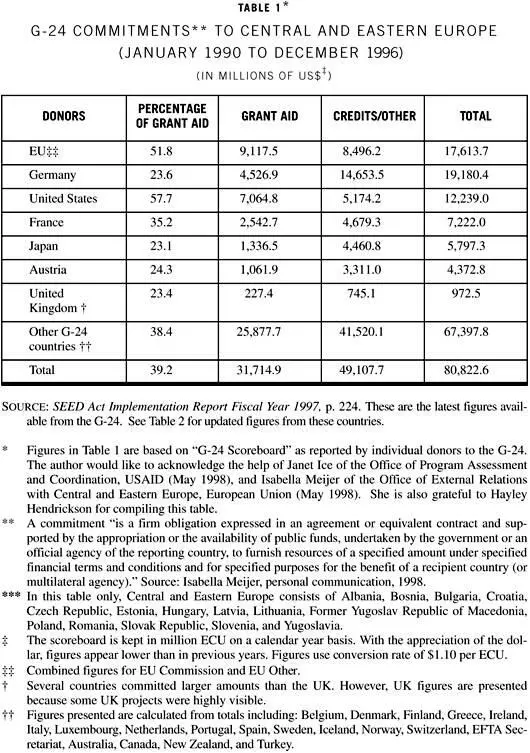

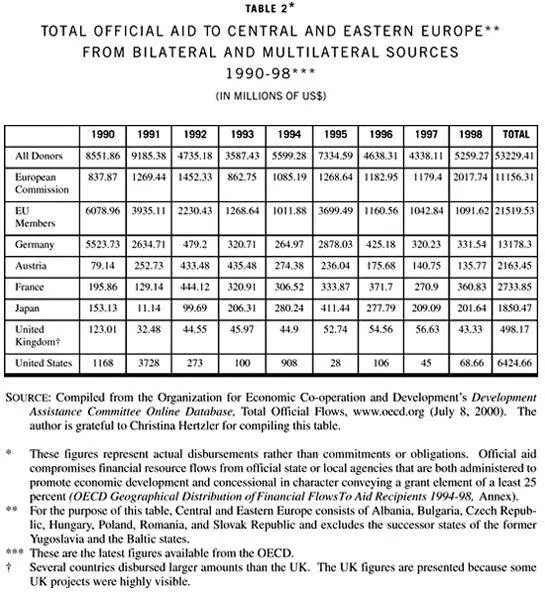

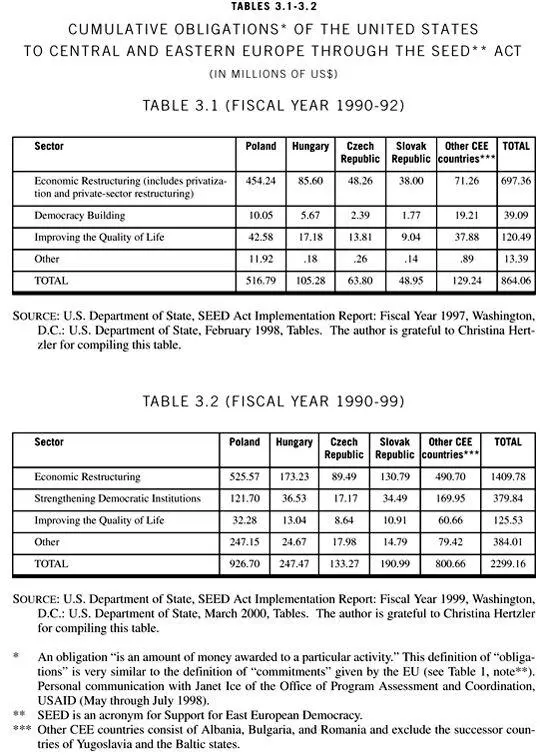

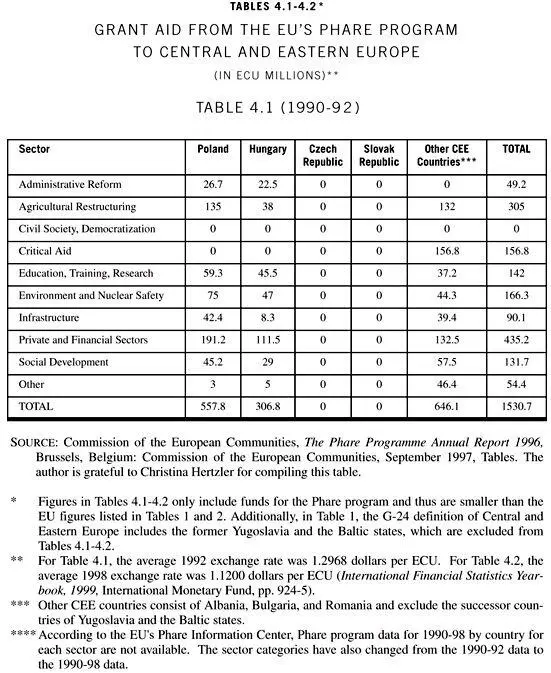

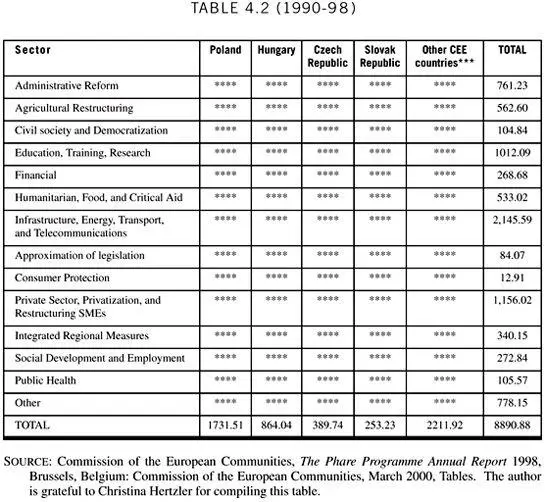

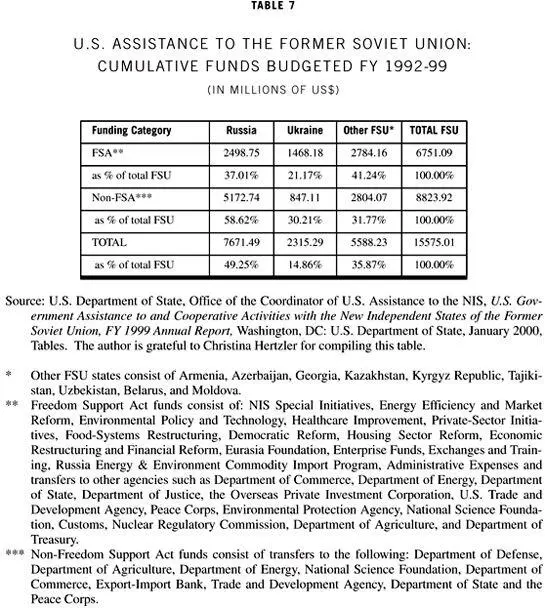

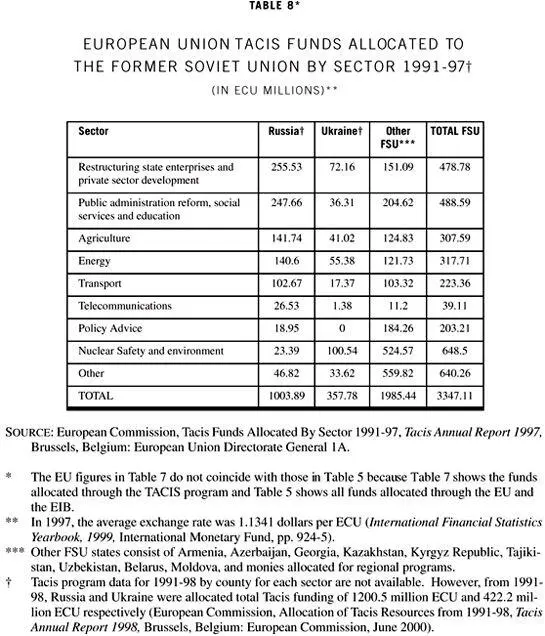

APPENDIX ONE

Tables

APPENDIX TWO

Methodology

This study is an ethnography across levels and processes, as set forth in the introduction. To capture the aid story, I have followed aid issues through actors and processes on both donor and recipient sides, with aid as the common thread. Interactions between donors and recipients occur on (and between) several levels and over time. In conducting an ethnography of foreign aid across levels and processes, I worked in multiple settings and charted the interactions among parties to the aid process. I employed a technique that some anthropologists have called “studying through.” As Cris Shore and Susan Wright explain it, studying through “entails multi-site ethnographies which trace policy connections between different organizational and everyday worlds even where actors in different sites do not know each other or share a moral universe.”1

Читать дальше