Still, many U.S. officials have argued that the most effective method of implementing market reform is through a committed group with intimate access to both sides (and to many activities in both countries). Yet this mode of organizing relations has served to undermine democratic processes and the development of transparent, accountable institutions in Russia. By systematically bypassing the democratically elected parliament, U.S. aid flouted a crucial feature of democratic governance: parliamentarianism. Operating by decree was clearly anti-democratic and contrary to the aid community’s stated goal of building democracy. Further, setting up flex organizations to supplant the state and indeed, an entire informal parallel executive further weakened the message to the Russians that the United States stood for democracy. Finally, providing a small group of power brokers with a blank check inevitably encouraged corruption on both sides, precisely at a time when the international community should have been demanding the development of a legal and regulatory framework that protected property rights and the sanctity of contracts.

There were other, more constructive scenarios possible in this story, had the donors chosen to devote the bulk of their efforts to working with and helping make government more effective, rather than simply bypassing it through top-down decrees and chameleon-like organizations, and had donors attempted to broaden their base of recipients and supported structures that all relevant parties could participate in and effectively own. A leading American university might have played a more positive role toward this end.

Building lasting, nonaligned institutions is a tough assignment in any context, and all the more so in Russia, especially given the time frame in which some legislative bodies like to see “results.” The major challenge in the post-Soviet environment is to work out how to help build bridges in such a conflict-laden environment, with many groups but few center coalitions. There has been a growing realization on the part of some U.S. aid officials that aid was not just a technical matter, but a complex task with political challenges that had to be faced. As Keith Henderson, head of USAID’s rule-of-law program for Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, has said, “We realized in Russia that it was important to work with many different players and one way to do that was to work with different [U.S. and European] contractors who worked with different players. We knew it was important to have all of these different people in the process.”229 Choosing one group was merely the path of least resistance, which promised toutable short-term results but with troublesome long-term outcomes.

To foster reform, donors need to work to develop a market infrastructure that all relevant parties can support—not just one political faction. As one aid-paid consultant expressed it: “One of the hardest parts of Western aid … was figuring out how to build member-owned, member-driven organizations that are neutral third parties and don’t have a vested interest in the success of one or several parties.… The hardest thing to get people over is political ties … to get leaders of organizations to seek opinion and perform for people who aren’t political buddies.” It is by no means an easy job, but the task of aid workers is to build contacts and work with all relevant groups toward the creation of transparent, nonexclusive institutions. There must be pressure to build institutions and against concentrating so much influence in the same hands, even if this goal is difficult to achieve. Only by truly encouraging such changes—not by depending on “reformers” who prevent them from taking the steps that must be taken—can the aid community make a genuine contribution to enduring positive change.

CHAPTER FIVE

A Few Good Financiers: Wall Street Bankers and Biznesmeni

It’s typical of every fund that they set out to do something with small and medium sized enterprises and then it became clear that it’s not so easy.

—Marek Kozak, head of an aid-funded program to foster business development in Poland1

IF DONORS CONFRONTED A TRADE OFF between the latitude they conferred upon consultants and recipients to design and implement aid programs and their own control and oversight of these programs (as seen in the types of aid discussed in chapters 2 through 4), there was equally a balance to be struck in yet another area of aid to the Second World: assisting private business in diverse and rapidly changing business environments.

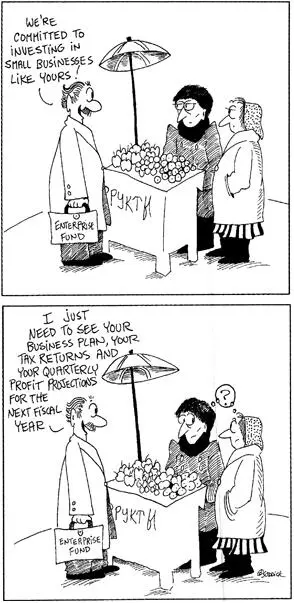

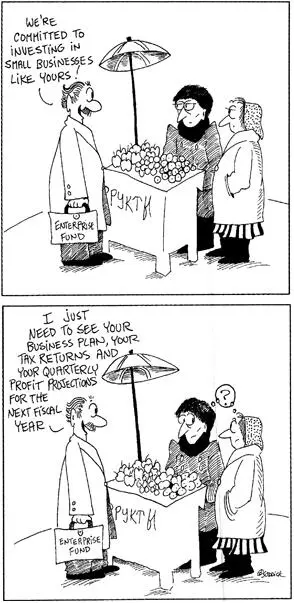

The disintegrating Eastern Bloc ushered in a new era of what the Poles called biznes— mom-and-pop service industries and traders hawking everything from bananas to computers. An important stated goal for Western donors—and a key to creating competitive markets—was to provide support for new small and medium-sized businesses and especially to help foster stronger, more highly developed business sectors as a prerequisite to the development of a market economy and democracy.

In lending support to this sector, donors employed a combination of aid approaches—sending Western consultants and funding indigenous groups—described in chapters 2 through 4. The consultants were loan officers or advisors on such issues as how to write a business plan; the groups were newly emerging “businesses”—often family members or partners of previous acquaintance.

Like the privatization of state-owned companies, the creation of a new business sector carried symbolic weight for the donors. Under socialism, business had been either heavily restricted, or, as in the Soviet Union, totally outlawed and pushed into an underground economy. The creation of a flourishing business sector was an integral part of entombing the socialist state and creating a capitalist one.

However, Central and Eastern Europe was a diverse landscape of fluctuating business conditions and of changing politics and domestic and external economic constraints. It would be very difficult to strike a balance between incorporating knowledge of local business practices, conditions, and needs of a given time and place and imposing donor standards and oversight.

FAMILY BUSINESS

Just what was the “private sector” in Central Europe circa 1990, and in what fields could foreign aid programs play a useful role? This question could not be answered once and for all: given that biznes practices and conditions varied considerably over time and place, there were differences in the need and demand for any kind of business support. In the immediate post-1989 aftermath in Central Europe, new opportunities for trade seemed to open up for a few weeks or months, only to close again. Legal infrastructure and enforcement and financial terms were in flux.

The communist legacies that shaped the emergent business sectors, and the effects of those legacies on further development, however, were steady. Part of the private sector was comprised of formerly state-owned companies that private people—often former nomenklatura managers—had simply “made one’s own.” Put another way, these companies had been “privatized” by virtue of state managers having acquired them. (See chapter 2 for discussion of the privatization of state-owned enterprises.) The other, more dynamic, part of the private sector consisted of new business.

In Poland under communism in the 1980s, the legal private sector—which included much of agriculture, construction, small shops, restaurants, handicrafts, and taxis—was the largest in the region. It generated nearly one-fifth of the national income and employed nearly one-third of the work force in the early 1980s.2 Despite the considerable risks entrepreneurs still had to assume to operate in 1990, the number of businesses increased from 805,879 on January 1, 1990, to 1,028,484 on August 8, 1990.3 Such activity was grounded primarily in trading, not acquisition of state resources and property.

Читать дальше