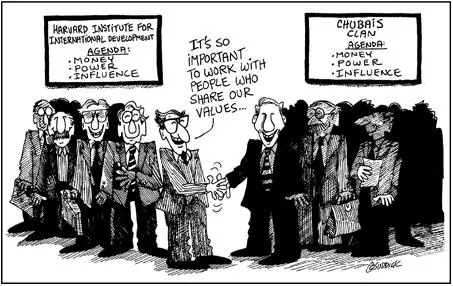

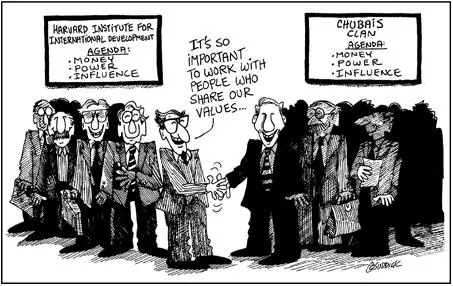

It had been damaging enough when Western donors selected a few groups in Central and Eastern Europe to receive aid, especially when the donors barely knew whom they were supporting. But in Russia (and later Ukraine), major donors—particularly the United States—took this approach to an extreme. The United States placed its economic reform portfolio—set up to help engineer the enormous shift from a command economy to free markets—into the hands of a single group of self-styled Russian “reformers.” From 1992, when aid first appeared, through much of the decade, U.S. economic aid to Russia was entrusted to these men, who were dominated by a long-standing group of friends from St. Petersburg that Russians called a “clan” (here referred to as the “St. Petersburg Clan” or the “Chubais Clan,” after its leader, Anatoly Chubais). This Clan worked closely with Harvard University’s Institute for International Development (HIID) and its associates to establish and run a Moscow-based program that leveraged U.S. support. The program served as the gatekeeper for hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and G-7 taxpayer aid, subsidized loans, and other Western funds and was known simply as the Harvard Project.3

The Clan came to control, directly and indirectly, millions of dollars in aid through a variety of organizations that were set up to bring about privatization, legal reform, the development of capital markets, a securities and exchange commission, and other economic reforms.4 Through these organizations, two Clan members alone became the gatekeepers for hundreds of millions of dollars in aid money and loans from international financial institutions. U.S. support also helped to propel Clan members into top positions in the Russian government and to make them formidable players in local politics and economics. U.S. support bolstered the Clan’s standing as Russia’s chief brokers with the West and the international financial institutions. The aid seemed to yield results, notably the transfer of a large number of state-owned companies to “private” ownership.

But was economic reform the driving agenda of the Chubais Clan? And what made it deserve the status of partner with the West more than other Russian reform groups? More important, did the strategy of focusing largely on one group further the aid community’s stated goal of establishing the transparent, accountable institutions so critical to the development of democracy and a stable economy for this world power in transition? As in Central Europe, what were the long-term implications in Russia of supporting one group of reformers at the expense of others? From the very beginning, Russian observers took note of the activities and motivations of the Chubais Clan. But it would not be until the late 1990s—and the eruption of a scandal that could hardly be ignored—that many Western observers would begin to consider the implications of U.S. and Western policy and what it had wrought.

THE FORGING OF THE HARVARD—ST. PETERSBURG PARTNERSHIP

In the late summer and fall of 1991, as the vast Soviet state was collapsing, Harvard professor Jeffrey Sachs and other Western economists participated in meetings at a dacha outside Moscow where young “reformers” planned Russia’s economic and political future. Boris Yeltsin, then in the leadership and undermining Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet Union (which would break up by year’s end), was building his teams of advisers—and the men from St. Petersburg were to figure prominently in that team. Their vital Western contacts distinguished them from other groups looking to have a hand in shaping Russia’s economic policy.

It was the springtime of East-West courtship. Russia seemed a blank slate ready for reform; dramatic change was in the air. The West fell in love with the new faces cast from its own ideological mold, and this cadre of “reformers” assumed the role that the West had created for them. They promised quick, all-encompassing change that would remake Russia in the Western image and eliminate the vestiges of communism.

At the dacha, Sachs and several other Westerners, some of whom were senior members in a project paid to Sachs’s consulting firm, Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates, Inc.,5 offered their services and access to Western money. They would provide the theory and advice to reinvent the Russian economy. The key Russians present were Yegor Gaidar, the first “architect” of economic reform, and Anatoly Chubais, who was part of Gaidar’s team and later would replace him as the “economic reform czar.” Individual Russians paired off with their Western counterparts to work on economic policy. Chubais, with his savvy, American self-starting style, found common ground with Andrei Shleifer, a Russian-born émigré who, still in his early 30s, had climbed to the pinnacle of academic success in America as a tenured professor of economics at Harvard and who served as a senior member in Sachs’s consulting project named above. Shleifer met Chubais through Sachs, according to a book co-authored by Shleifer.6 Both Shleifer and Chubais were young, ambitious, and apparently eager to make economic policy history. They combined forces to plan the privatization of Russia’s state-owned enterprises.

Supporting the Sachs-Gaidar-Chubais policies (though not at the dacha meetings) was yet another Harvard man, Lawrence Summers. In 1991, Summers was named chief economist at the World Bank. Summers would later occupy the posts of undersecretary, then deputy secretary, and, finally, secretary of the Treasury. In 1993, newly inaugurated President Clinton appointed Summers under secretary of the Treasury for international affairs. In this role, Summers was directly responsible for designing Treasury’s country-assistance strategies and for the formulation and implementation of international economic policies.7 He had deep-rooted ties to the principals of Harvard’s Russia project. Shleifer credits Summers with inspiring him to study economics;8 the two received at least one foundation grant together.9 Summers’s publicity quote for Privatizing Russia, a book co-authored by Shleifer, declares that “[t]he authors did remarkable things in Russia and now they have written a remarkable book.”10

Summers had also long been connected to Sachs, his colleague from Harvard. Summers hired Sachs’s protégé, David Lipton, a Harvard Ph.D. who had been vice president of Jeffrey D. Sachs and Associates (and who, together with Sachs and Shleifer, was listed as a senior member of the Sachs consulting project), to be deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury for Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. After Summers was promoted to deputy secretary in 1995, Lipton moved into Summers’s old job and assumed “broad responsibility” for all aspects of international economic policy development. Lipton and Sachs published numerous joint papers and served together on consulting missions in Poland and Russia. “Jeff and David always came [to Russia] together,” remarked Andrei Vernikov, a Russian representative at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). “They were like an inseparable couple.”11 According to Vernikov and other sources, Sachs presented himself as a power broker who could deliver Western aid.

Sachs helped Gaidar, who served as minister of finance and the economy from November 1991 to April 1992, then as first deputy prime minister, followed by acting prime minister to December 1992, promote a policy of “shock therapy,” which aimed to swiftly eliminate most of the price controls and subsidies that had underpinned life for Soviet citizens for decades.12 Gaidar, Sachs, and their supporters believed that such a policy would lift the nation out of the doldrums of its command economy and set it on the bright road to capitalism. Shock therapy did free most prices, but it did not pay sufficient attention to the fact that the economy was monopolistic. Many experts believed that shock therapy contributed significantly to the subsequent hyperinflation of 2,500 percent. One result of the hyperinflation was the evaporation of much potential investment capital: the substantial savings of ordinary Russians.13 By November 1992, Gaidar was under severe attack for his failed policies. He was ousted in December of that year. Despite a brief return as first deputy prime minister, Gaidar continued his policy influence primarily behind the scenes.

Читать дальше