The Bureau of Research was developed largely on the model of the U.S. Congressional Research Service. When, in 1994, the United States ended its assistance, the European Parliament and the Council of Europe assumed some of the functions of education and training that the Congressional Research Service had previously provided. The Europeans encouraged an expansion of initiatives to “harmonize” Polish laws with those of the EU in preparation for Polish accession to it.112

Impartiality was a key component in the assistance offered and in the Bureau’s survival and good reputation. In time, the Bureau became self-sufficient, with its operating budget funded by the Polish Parliament and Senate.113 By 1998, it had fully convinced the Polish government of the necessity of such an impartial institution, according to director Staszkiewicz. He said the bureau had survived a succession of governments in a partisan environment because of its insistence on remaining neutral.

As of mid-1998, the Bureau of Research had issued some 19,000 expert opinions to Parliament upon request and had become one of the best operations in Europe. The Bureau has been engaged—and is expanding its efforts—to help set up similar offices in nations to the south and east of Poland. What has been most difficult to explain in Romania, Albania, and Bulgaria, observed Staszkiewicz—but is crucial—is that such an office must remain nonpartisan.114

* * *

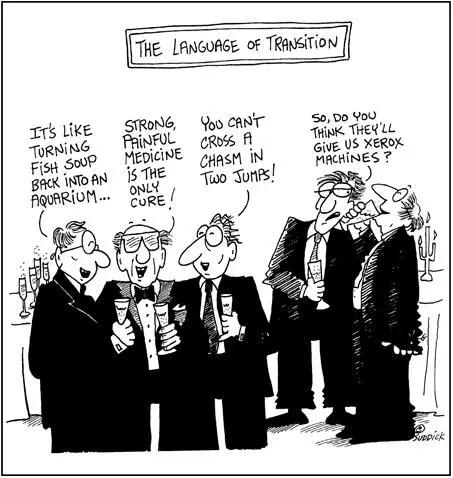

Changing views about Western aid were in evidence in Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic by 1994. Despite mistakes, and the resentment they engendered, much of the antagonism present in Central Europe in the first years of the aid effort had dissipated. Recipients adapted as their experience with donors grew and led to another phase of aid relations: Adjustment. After early frustration and resentment about the inadequacies of foreign consultants and the help they offered, Central European officials became better at identifying their needs and more selective about foreign (and local) advisers. As consultant Pappalardo observed in 1994, there were “a lot of carpetbaggers early on.… At this stage of the process Poles are more aware of the things they know and, most importantly, of the things they don’t know. They’ve learned to clarify their needs.”115

Regardless of whether much of the technical assistance rendered was effective, a natural progression occurred. As Poles, Hungarians, and Czechs developed technical capacities, the need for foreign aid–sponsored technical assistance diminished.116 They developed new skills for dealing with the donor community and became more realistic about what aid could (and could not) do for them. In some cases, they concluded that the costs of working with an aid program, in terms of timing and meeting donor requirements, outweighed the benefits, and they chose not to do so.

A related development was the blurring of distinctions between donor and recipient personnel. Initially, it had been possible to detect just who was who by nationality, language, style, and dress. By 1994, however, many Western consulting groups, including accounting firms, were hiring more local citizens and expatriates who spoke Polish, Hungarian, Czech, and Slovak. Donors also recruited some former high-level Central European officials who had served in the first postcommunist governments. For example, the Polish-American Enterprise Fund hired a former deputy minister of privatization and a former undersecretary in the Ministry of Industry and Trade to be vice presidents. Marek Kozak, who, two years earlier, had criticized Western aid efforts, headed a private-sector development initiative for the EU. Some Central European consultants, by then anointed “Westerners” themselves, even served as the new missionaries of the West and helped spread the gospel of reform in the East.

The extent to which these consultants, as well as those based in the donor countries, could be useful largely depended on how aid was designed and the relationships it engendered with various recipient parties. Helping to build up independent institutions was especially important in environments in which information and expertise unconnected to a political group or agenda was under constant attack. Exercising as much independence as possible was crucial precisely where it was most difficult to remain neutral and professional. At no time would this be more apparent than when the West, hoping to help create democracy, civil society, and an independent sector where none supposedly had existed for nearly 50 years, funded partisan groups. Through the weightiest years of the aid effort, many of these groups would seek to enhance their own agendas, rather than to further the noble goals of the donors.

CHAPTER THREE

A Few Favored Cliques

The various political shifts and upheavals within the communist world all have one thing in common: the undying urge to create a genuine civil society.

—Václav Havel, 19881

WHILE DISPATCHING CONSULTANTS ACROSS THE OCEAN as its agents of change, the West also set out to supplant communism by supporting certain local organizations and groups as exemplars of and vehicles for creating democracy and a civil society. This approach held that, under communism, the nations of the Eastern Bloc never had a “civil society,” in which citizens and groups were free to form organizations that functioned independently of the state and that mediated between citizens and the state.

Because this lacuna epitomized the all-pervasive communist state, both Western and Central European opinion makers saw creating a civil society and independent organizations as building the connective tissue of a new democratic political culture. The experience and writings of Central European dissident intellectuals such as Václav Havel in Czechoslovakia and Adam Michnik in Poland helped crystallize the view of an idealized civil society2 playing a vital reconstructive role in the former communist states. Although the concept subsequently became central to how donors thought about Central and Eastern European “transition,” in the recipient societies, the idea tended to be limited to certain circles. It was not, for example, necessarily shared by large segments of the various populations (not even by parts of the Opposition close to Poland’s Roman Catholic Church).

The building blocks of civil society were thought to be nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which donors also saw as important vehicles of technical assistance and training. Donors had high hopes for this “independent sector”: It was to replace the discredited centralized bureaucratic state, decentralize services, and build democracy. And so donors made the development of a civil society and support of NGOs a primary focus, if not always as a funding priority, certainly in rhetoric.

Americans tended to talk the loudest about establishing civil societies in the region.3 The fall of the Berlin Wall energized American efforts to try to remake Central and Eastern Europe in “our” image by exporting the can-do mentality and the tradition of citizens’ initiatives and local governance. The U.S. Congress obligated some $32 million in 1990-91 to support “democratic institution building” in Poland and the other ex-communist states.4 By the end of 1999, the United States had obligated $379 million to promote political party development, independent media, governance, and recipient NGOs.5 Many of these projects were carried out through grants to American quasi-private organizations, notably the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and its affiliated institutes, including the AFL-CIO’s Free Trade Union Institute (FTUI), the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), and the National Democratic and National Republican Institutes for International Affairs (NDI and NRI). A host of American NGOs, seasoned by USAID- and foundation-supported work in the Third World, also lobbied and competed with each other for the new business.

Читать дальше