NRI

National Republican Institute for International Affairs, United States

NSC

National Security Council (U.S. government body)

ODA

Overseas Development Administration (UK government body)

ODA

Official Development Assistance (development category)

OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (based in Paris)

PFP

Partnership for Peace (program for military cooperation with Central and Eastern Europe)

PHARE

Poland and Hungary Aid in Restructuring the Economy (EU program)

PMU

Program Management Unit

ROAD

Ruch Obywatelski Akcja Demokratyczna or Citizens’ Movement for Democratic Action (former Polish political party)

RPC

Russia Privatization Center (USAID-funded organization in Russia)

SEC

Securities and Exchange Commission (U.S. government body)

SEED

Support for East European Democracy Act

TACIS

Technical Assistance for the Commonwealth of Independent States (EU program)

UNDP

United Nations Development Program

USAID

United States Agency for International Development (also known as AID)

A NOTE ABOUT TERMS

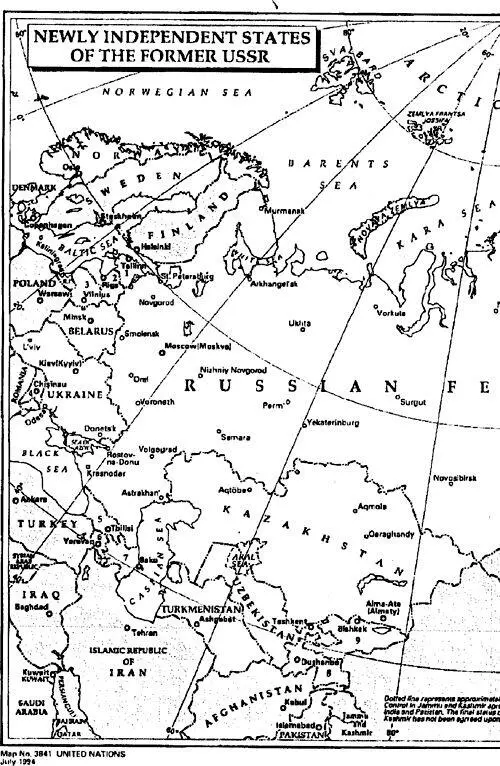

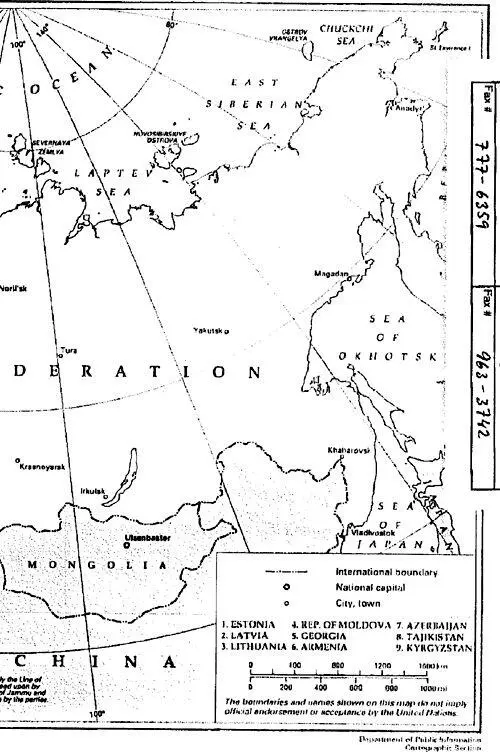

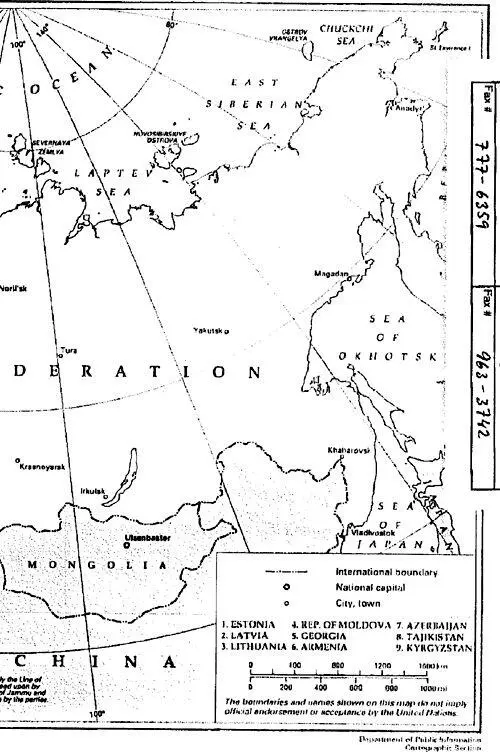

“Central Europe” here refers to the Visegrád countries of Poland, Hungary, and former Czechoslovakia, on which this study concentrates. “Central and Eastern Europe” includes the Visegrád countries of Central Europe and two largely European countries of the former Soviet Union—Russia and Ukraine.

I use the terms “communism” and “socialism” (as well as “communist” and “socialist”) interchangeably to denote the system that prevailed in the Eastern Bloc countries and the Soviet Union. I find both these terms somewhat inadequate: while “communism” in its pure form was never achieved, “socialism” would also seem to apply to some vastly different northern European nations.

“Second World” here refers both to the nations of the former Eastern Bloc and the former Soviet Union.

A NOTE ABOUT INTERVIEWS

I personally carried out hundreds of interviews for this book. Unless otherwise specified, I conducted all interviews cited in the text and in endnotes. (See Appendix 3: Interviews.)

Janine R. Wedel

INTRODUCTION

Some Enchanted Era

ON AN EVENING IN FEBRUARY 1991, at the conclusion of an official banquet held in an opulent room of the U.S. Department of Treasury building, a chamber orchestra played Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Some Enchanted Evening.”

For many of those in attendance—elegantly dressed men who had earlier participated in a conference titled “Economies in Transition: Management Training and Market Economies Education in Central and Eastern Europe,” cosponsored by the White House and the Treasury Department—it may well have seemed an enchanted evening. One year earlier, after the fall of the communist East Bloc, the United States had authorized nearly $1 billion in aid to the region to “promote the private sector, democratic pluralism, and economic and political stability.” With that aid effort heating up, the conference brought leaders from the region together with officials from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which led the aid effort, along with other U.S. agencies and representatives of the private sector to discuss and coordinate aid programs.

At the conference, high officials offered more optimism than substance or experience. One of these officials assured the visiting Central and Eastern Europeans: “America will not fail you. It will stick with you in this decisive moment.” The West had an important role to play by assisting in the transition to democracy, he said, and would not squander the opportunity.

The “need for transition” to democracy and a market economy and the need for training, upon which everyone agreed, seemed to be repeated a hundred times. Speakers echoed the truisms they and the “experts” had uttered with missionary zeal at dozens of similar conferences. The need for change away from centrally planned economies had spawned a number of metaphorical clichés of “transition.” An Eastern European minister parroted this trendy mantra: “It’s easy to make an aquarium into fish soup. But can the fish soup be turned back into an aquarium?” Going from communism to capitalism would be no less dramatic and difficult. “Strong medicine” would be required to “jump to a market economy.”

The Central and Eastern Europeans, who had been brought over specially for the conference, listened politely. Behaving (and being treated) more like bystanders than participants, they did nothing to undermine its upbeat tone, all the while underscoring the difficulty of transition in that charming, understated style in which the savvy elites of poor countries often present themselves.

Away from the music, I spoke with a Polish official who was to coordinate foreign assistance to his country. He was too gracious and well bred to be overtly critical of the conference. After a long conversation, however, he meekly suggested that some “training of the donors” might be helpful. He said he was struck by how Americans seemed driven to do good and thought they could just draft a statement and assume that good would follow. “But that isn’t enough,” he said. “They need to have some idea about what they’re trying to accomplish.”

Indeed, in the aid story, ideas about what could or should be accomplished have not always been wise or wisely set in motion. Problems that would emerge later in the field as aid arrived in Central and Eastern Europe and the nations of the former Soviet Union could be seen to take root in that banquet room on that “enchanted evening.” The conference was symbolic of a genuine desire to do good and at the same time exposed a wide gap between the two sides—a gap in perspectives, goals, and experience. In the years ahead, that gap would grow wider before it narrowed and would create a situation in which many were far from enchanted with aid efforts.

THE DISCONNECT

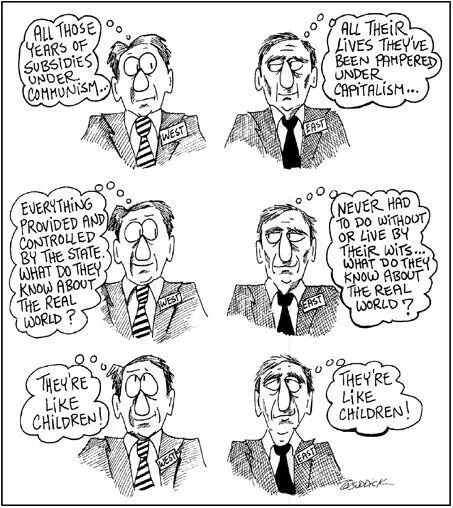

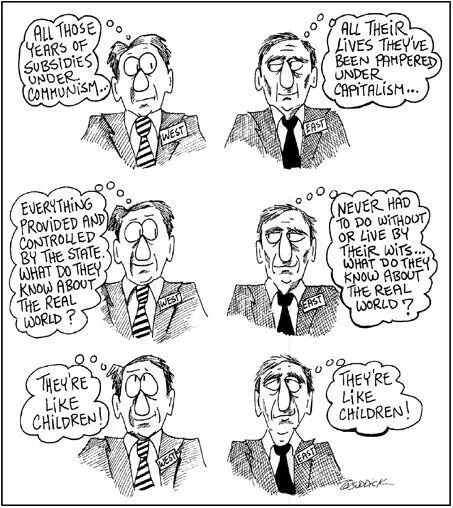

At the start of the aid story, there was a gigantic disconnect between East and West—a disconnect forged by the Cold War and exacerbated by the barriers of language, culture, distance, information, and semiclosed borders. Before the revolutions of 1989, only a handful of scholars, journalists, diplomats, and descendants of emigrants from nations in the region had ventured behind the Iron Curtain. By the end of the decade, the volume of foreign traffic flowing through Central and Eastern Europe was enormous. Yet the disconnect lived on, even as circumstances changed after the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

I was in a unique position to observe the disconnect: When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, I had already spent six years in Poland as an anthropologist, Fulbright scholar, and freelance journalist. I had a wealth of friends and acquaintances, many of whom were to become leaders in politics, business, and public life. Before the collapse of communism opened up so many new avenues to the West, the region’s 40-plus years as a semiclosed world had shaped the many expectations natives had of foreigners and their ways of relating to them. I had observed how Poles welcomed foreign guests and showered them with hospitality and graciousness. Westerners were the bearers of gifts and opportunities. But at the same time, many Poles regarded Westerners as childlike because they were naive about the hard realities of the Eastern world as well as the political skills it took simply to survive under communism. I had recorded what I came to call the Poles’ ritual of listening to foreigners, in which the naive but self-assured Westerner would encounter the shrewd Pole, who deftly charmed his guest while revealing nothing of what he truly thought. The same Pole would laugh at the Westerner’s gullibility behind his back, as one might poke fun at a child. Many Poles had mastered the sophisticated art of impressing Westerners while maneuvering to get what they wanted.

Читать дальше