In time, the paper-thin deceptiveness of the slogans of transition became apparent. Although metaphors of turning fish soup back into an aquarium, having a tooth pulled, or crossing a chasm were colorful ways of explaining a position, they represented a bumper-sticker mode of thinking. After all, what made “transition” away from a centrally planned economy like resurrecting fish from fish soup, like having a tooth pulled, or like crossing a chasm? As anthropologist Mark Hobart has pointed out, when the metaphorical images so frequently used in development discourse to justify policies are removed, “the degree to which many theories require modification or rethinking is remarkable.”102

These metaphors seemed especially ludicrous in light of the legacies of communism that would figure prominently in the aid story. According to Marxist theory, the state was eventually supposed to have withered away. The reality was that, under communism, Eastern European states had developed “state socialism”: strong, centralized bureaucracies that maintained their power by controlling the distribution of goods and services.103 The tradition of tight integration between politics and economics rendered separation of the spheres difficult—and made it nearly impossible to depoliticize post-1989 assistance. Because so many areas of the economy and life were under political control, the detachment of political motives from economic ones was unthinkable for many Central and Eastern Europeans. As a consequence, even after communism had been dismantled, the tradition of suspicion continued—and infected Eastern perceptions of Western motivations.

Moreover, donors’ agendas were inherently political. Donors set out to tear down communism and to encourage civil society and democracy. Although these agendas were welcomed by most Eastern Europeans, they exposed the intrinsically political nature of “economic” aid. As suspicion surrounded Western motives for supplying aid and the new leaders who accepted it, the idea of the “West as demon” would also resurface in powerful ways. Many people began to believe that perhaps the communists had been partially right about Western imperialism and capitalist exploitation.

Amid the euphoria of the early months of the aid effort, these difficulties had barely started to become apparent to the Central and Eastern Europeans eagerly awaiting bounty from the West. It was not until later—into 1991, 1992, and beyond—that the East began to recognize that Western “help” meant mostly advice—and that this advice was not necessarily designed to benefit and serve the needs of its recipients. Only then could a Czech politician launch his political career by waging a campaign against a Western aid program; only then would Polish President Lech Wałęsa angrily charge that “it is you, the West, who have made good business on the Polish revolution.”104 Most important, it was not until then that many people across Central and Eastern Europe, from factory workers and truck drivers to local bureaucrats, would begin to lose faith in the West and the system it represented, even if only temporarily. This loss of faith encouraged some groups and individuals to take matters into their own hands.

As hopes diminished, people became more suspicious of, and ambivalent toward, Western aid. Latent images of the West as “demon” that had lain dormant during the Triumphalist period began to resurface, as the phase of Disillusionment—frustration and resentment—came into its own. Just as the West as saint had written the script for Triumphalism, so the West as demon was to help set the scene for Disillusionment.

CHAPTER TWO

Consultants for Capitalism

Officials here get tired of answering the same questions without anything coming out of it. The Western consultants collect information, get the picture, then they go home.… We are not really satisfied with this technical assistance. We are solving the West’s unemployment in this way.… We get calls from ministries that receive consultants from all over asking if aid can be reduced.

–Jarmila Hrbáčková, Slovak aid official1

I’m not sure we hit on the right model for technical assistance.

–Ambassador Robert Barry,

Special Adviser for East European Assistance to the Deputy Secretary of State2

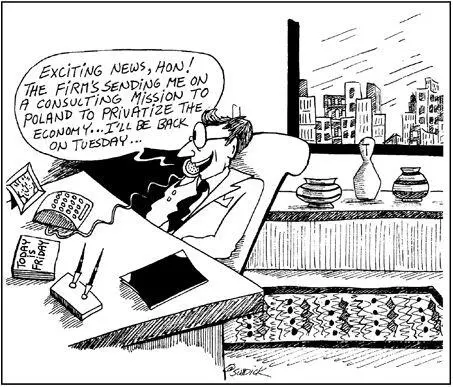

IF BIG EASTERN EXPECTATIONS paired with ill-designed Western aid presaged problems from the very beginning, the exploits of the “Marriott Brigade” drove East and West even farther apart. The Marriott Brigade was a term the Polish press coined for the short-term, “fly-in, fly-out” consultants hired by aid donors who delivered technical assistance.3 They stayed at Warsaw’s pricey new Marriott and hurtled among five-star hotels across the region. In contrast to long-term consultants, who stayed for months or even years, members of the Marriott Brigade appeared in the region for several days or weeks. They were nattily dressed and quick with words and promises, and Central European officials, many of whom were new at their jobs, welcomed them at first. The officials’ doors were always open in those early days. But after hundreds of “first meetings” with an endless array of short-term consultants from the World Bank, the IMF, the EU, USAID, and other organizations, many host officials concluded that a certain degree of skepticism was in order. And so as early as 1991, the honeymoon was largely over in Warsaw, Budapest, and Prague. The same performance, with the same unhappy result, was repeated as the aid frontier moved east, to Russia and then to Ukraine.

What went wrong? The answer involved a complex collision of cultural and institutional realities and was rooted in the swollen responsibility that the donors bestowed on uninitiated consultants for complicated and politicized reforms such as the privatization of the region’s state-owned assets.4 Privatization involved the transfer of ownership of state enterprises or parts of enterprises to firms, individuals, or other nonstate entities. The problem, as seen on the ground, boiled down to relationships. Amid a striking lack of consensus between East and West about what had been promised and what was being delivered and about who was supposed to benefit from all the programs and reports and advice, many Marriott Brigaders failed to establish working relationships with their presumed counterparts.

On the other extreme, some consultants developed “crony relationships” with a few local elites for mutual profit. The involvement of foreign advisers in one of the most politicized processes in the transformation of Central and Eastern Europe sometimes served to rekindle the region’s traditional condemnations of the imperialist West and its well-honed practice of pulling the wool over the naive foreigners’ eyes. By the time the Marriott Brigade had checked out and headed home, many Western attempts designed to encourage privatization and other high-priority reforms, as defined by the donors, were well on the way to costly failure.

THE ECONOLOBBYISTS

A few high-profile economists laid the groundwork for the swarm of Marriott Brigade consultants that would follow. Although some steadfast and persistent advisers made contributions in the region, the jet-setting “econolobbyists” were more about public relations and their own publicity than they were about serious policy advice. Although not necessarily funded by government aid programs (Western foundations were frequent supporters), the econolobbyists, through their promises and illusive relationships with their hosts, created an image of Western consultants that persisted throughout the aid saga. In the West, the econolobbyists wrote op-ed pieces, delivered speeches calling for aid, and thereby helped define the “reform” agenda. They were perceived as able to effect market reforms in the East. In the East, the econolobbyists’ value was seen in their ability to deliver Western money and access and to help policymakers “sell” controversial reforms in the transitioning countries.

Читать дальше