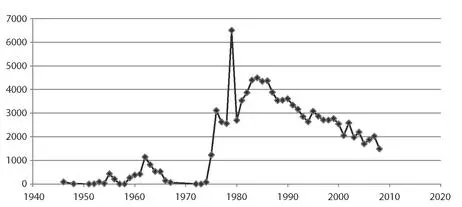

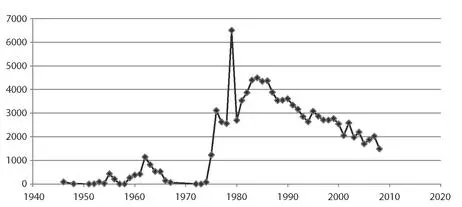

The recognition of Israel was an extremely unpopular policy shift in Egypt. This is why Sadat could extract so much from the United States. Unfortunately for Sadat it also led to his assassination in 1981. Fundamentalists threw grenades and attacked with automatic rifle fire during an annual parade. Although it officially recognizes Israel, the Egyptian government has done almost nothing to encourage the Egyptian people to moderate their hatred for Israel. In a BBC survey conducted nearly thirty years after the Camp David agreement was struck, 78 percent of Egyptians indicated that they perceive Israel as having a negative impact in the world, far above the average in other countries whose citizens participated in the BBC survey on this question. 12 Of course, changing the negative attitude toward Israel in Egypt would just reduce the amount of aid the Egyptian government could extract from the United States.

FIGURE 7.1 Total US Assistance to Egypt in Constant 2008 Million US$ from USAID Greenbook

Recent movement toward a more democratic government in Egypt highlights the dilemma faced by democratic donors. Those who celebrate the prospects of democracy in Egypt and favor peace with Israel have a problem. As we have noted, the aid-for-peace-with-Israel deal could be struck exactly because the autocratic Egyptian leadership and its coalition were compensated for the anti-Israeli sentiment among its citizenry, a sentiment they helped preserve. With the people now in charge, it would be natural for Egypt to shift away from its peace with Israel. To prevent that, greater amounts of foreign aid will be needed than was true under the Sadat-Mubarak dictatorships. Given the significance of Israeli-Egyptian peace to American and Israeli voters, it is likely that the higher price will be paid. That leaves the question, will that greater aid be used to strengthen the military or improve the lot of ordinary Egyptians?

As with Egypt, US assistance to Pakistan is much easier to explain by looking at aid as a payment for favors rather than a tool for alleviating poverty. In 2001, the United States gave Pakistan $5.3 million and Nepal $30.4 million in aid. Pakistan’s aid had been greatly reduced by congressional mandate following their test of a nuclear weapon in 1998. Yet, on September 22, 2001, US president George W. Bush lifted restrictions on aid. Pakistan received more than $800 million in 2002. Meanwhile, Nepal, not on the frontline of the fight against Al Qaeda and the Taliban, received about $37 million, just modestly more than their 2001 receipts. India, also not front and center in the battle against terrorism in 2002, received $166 million from the United States, up barely from 2001 when they received about $163 million. Poverty had not changed in any meaningful way in any of these countries between 2001 and 2002, but their importance to American voters most assuredly had.

Democrats are often perceived as being in the driver’s seat and dictating terms to autocrats. However, as in other matters, they are often the ones who are constrained. They need to deliver the policies their backers want. If they try to cut back on the aid they give or impose strict conditions, then autocrats simply end the policy concessions.

Subsequent US relations with Pakistan offer clear evidence of this pattern of waning and waxing aid. As we saw, aid went up following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, but then it began to taper as the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan seemed to have been won by 2003. Once Pakistan increasingly became a safe haven for the Taliban and Al Qaeda, everything changed. Pakistan now found itself in a tough spot. If the government opposed the Taliban who were infiltrating the Pakistani frontier with Afghanistan, they were likely to face a domestic insurgency. If they supported the Taliban they would face severe pressure from the United States. This dilemma offered an opportunity for Pakistan to make greater demands for US aid if Pakistan’s government was to be induced to resist the Taliban. The demands were made but the US Congress balked at giving Pakistan more, noting that much American aid to Pakistan was diverted to uses not intended by the Congress. These uses include the disappearance of some money and channeling much of the rest by Pakistan to stave off what the Pakistanis perceive to be the greater threat from India than from Muslim fundamentalist militants.

The United States, disgruntled with Pakistan, did not initially agree to pay the higher price needed to get the Pakistani government to pursue the Taliban and Al Qaeda militants within Pakistan. What was the upshot? As we have learned to expect, the Pakistani leadership ignored US pressure and began looking for ways to work with the Taliban. Aid is basically a pay or don’t play program. The United States wouldn’t pay and Pakistan wouldn’t play.

By 2008, the government of Pakistan’s leader Asif Ali Zardari, was paying only lip service to going after the militants. The Bush administration, lacking more aid to offer, proved unable to change Zardari’s mind. In fact, the second half of 2008 saw only a perfunctory effort by the Zardari government to fight the militants. There was a brief military offensive against the Taliban, starting on June 28 and ending in early July, with precisely one militant killed. After that, although the Taliban aggressively pursued their own territorial expansion in Pakistan, the Zardari government mostly looked the other way. Rather than fight the militants, Zardari’s regime made a deal with the Taliban in February 2009, paying them about $6 million and agreeing to the imposition of Sharia law in the Swat Valley in exchange for the Taliban agreeing to an indefinite ceasefire. The ceasefire unraveled by May. By this time, the Zardari government seemed in trouble and the US government was fearful that the Taliban might take control of Pakistan altogether. In the face of such dangers, the price for aid had risen but so too had the desire in the United States to motivate the Pakistanis to try harder to beat back the Taliban.

Congress passed the Kerry-Lugar bill at the end of September 2009. It nearly tripled aid to Pakistan, increasing it to $1.5 billion. Even then the Pakistani government balked at taking the greatly increased aid because the bill included requirements that the Pakistanis be accountable for how the money was used. Facing resistance from Pakistan, Senator John Kerry clarified that the bill was not designed to interfere at all with sovereign Pakistani decisions; that is, he essentially assured the Pakistani leadership that the United States would not closely monitor use of the funds. Shortly after, the Pakistani government accepted the aid money and greatly stepped up its pursuit of militants operating within its borders. By February 2010 they had captured the number two Taliban leader, but, as we should expect, they have also been careful not to wipe out the Taliban threat. Doing so would just lead to a termination of US funds.

The US government, for its part, is frustrated that even with $1.5 billion in aid, Pakistan is not sufficiently motivated to beat back the Taliban. As a result, the United States has stepped up drone attacks and the use of the American military to pursue the Taliban within Pakistani territory, much to the public—but we doubt private—dismay of the Zardari government. This is all just the dance of the donors and the takers, the recipients looking for as much money as possible and the donors looking for a highly salient, costly political concession: the destruction of the Taliban.

Perhaps this is distasteful to those who would like to maintain the fiction that aid is about alleviating poverty. Naturally some aid is given with purely humanitarian motives, such as that given after a natural disaster. Yet it is hard to reconcile the large scale of aid flows to Egypt and Pakistan with idealistic goals. If aid actually helped the poor, then we might expect the people in recipient nations to be grateful and hold donor nations in esteem. Nothing could be further from the truth. In return for its “benevolence” to Egypt and Pakistan, the United States is widely reviled by the people in those two countries; and with good reason.

Читать дальше