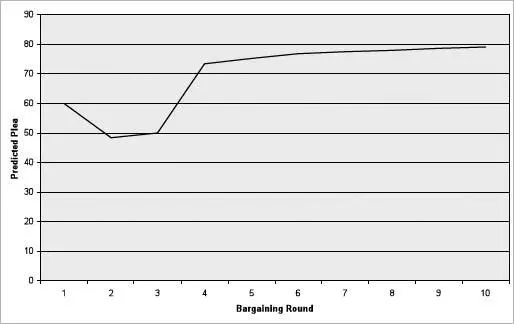

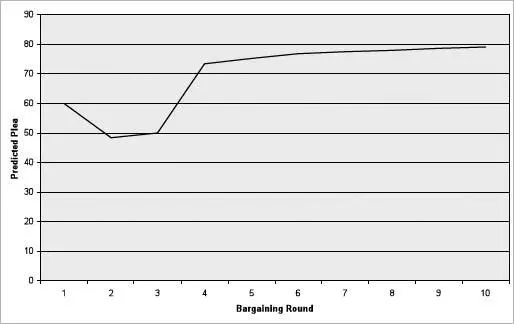

FIG. 6.1. The Unengineered Plea Path

According to the model, the give-and-take in settlement discussions would persist through eight meetings between the defendant’s representatives and the U.S. attorney or his/her representatives. At the end of the eight exchanges of views and arguments, the game indicates that the cost of continued negotiations was no longer going to be worth the small changes in the expected agreement. That agreement was just about at 80 on the plea scale—that is, one count of the severe felony plus several lesser felonies.

The result anticipated by most of my client’s lawyers and expected by the board, and the plea predicted by the end of the game, were the same. If my model couldn’t improve on this, then my consulting partner and I would have nothing to offer the firm that hired us. We would be just another expense.

However, the game uncovered something not anticipated by most of the attorneys (one senior outside attorney had the ultimate result dead right from the outset, although he/she did not quite see why it would arise or how to get there). The model’s simulation indicated that early discussions with the U.S. Attorney’s Office and others would suggest that a powerful coalition of interests was going to form around a lesser set of charges—almost like a gambit in chess, designed to suck the client and the U.S. attorney into a move that would be used against them later. The figure, which displays the predicted upshot of discussions at each stage in the negotiations, anticipates that the second and third presentation of arguments by the defendant’s side were likely to soften the U.S. attorney enough so that he/she would contemplate agreeing to 50, a better mix of multiple misdemeanor and felony counts not including a severe felony. This was, in fact, the position believed to be held by the U.S. attorney at the outset of negotiations, according to our interviews with the client’s representatives and attorneys. However, the initial analysis also showed that with subsequent rounds of discussion, the U.S. attorney could be and would be persuaded to take a tougher, not a softer, stance.

Why the move to a tougher stance after showing openness to a more moderate settlement? The model indicated that the hard-line attorneys in ABC and in the office of the U.S. attorney were going to execute a gambit. The ABC attorneys and the Department of Justice lawyers apparently were out to make names for themselves as tough guys who could bring evil corporations to their knees. The analysis suggested that they thought this was the perfect case to do it. Their gambit aimed to set up the U.S. attorney so that he/she would reveal softness early in settlement discussions. Then later they would pounce on this softness in order to embarrass the U.S. attorney politically, compelling him/her to take a tougher stance when it counted, in the end, lest he/she be tarred publicly with the ignominious tag of being soft on business malfeasance. That would not have played out well in the affected community or in the Department of Justice. To be sure, these lawyers were really rolling the dice, taking a big risk if their gambit failed. But they had every reason to think it would succeed—and probably it would have, had my client not been using a tool like the negotiating game.

Even though (according to the model) the U.S. attorney was willing to go for a mix of misdemeanors and lesser felonies, the logic showed that the hard-liner gambit would work. He/she would abandon a moderate stance, choosing instead to go for severe felonies. This was the U.S. attorney’s way of solving the tough choice between pursuing the outcome he/she thought was right and following the gambit’s path, thereby avoiding careerist costs and keeping the support of others in the Department of Justice and in the affected community. Seeing that the U.S. attorney had significant political exposure and careerist ego involvement in the case, it became apparent that we could find ways to gratify his/her ego and bollix the hard-liners’ gambit.

The simulations uncovered several interesting patterns that opened the opportunity to engineer the outcome. First, as noted, the U.S. attorney took a tough stance according to the simulations because of pressure from attorneys at ABC and within the Department of Justice and in response to arguments from several stakeholders in the affected community. They were strongly committed to their point of view, and the U.S. attorney cared about being perceived by them as interested in helping them get justice as they saw it. This was particularly interesting because the U.S. attorney’s own view of what could be supported as punishment through the judicial process was considerably less. The U.S. attorney’s view involved none of the severe felonies and showed openness to at least some misdemeanors. The U.S. attorney, facing hard-line pressure, was willing to trade off some sense of legal correctness for political correctness and its attendant personal credit.

To engineer a better result, I simulated what might happen if the defendants altered their bargaining position from that of being prepared to accept numerous misdemeanors and maybe one lesser felony, a posture predicted to end in their caving in to one or more severe felonies. I looked at what would happen if they offered more concessions up front and also if they offered less. I also looked at how they could maneuver to get some important hard-liners to make arguments that would make those hard-liners look foolishly extreme to the U.S. attorney, turning the gambit on its head. In examining alternative strategies I took advantage of another insight gained from the base analysis: the U.S. attorney tilted more toward eagerness to make a deal than to sticking to a particular position. Also, it was evident that the defendant’s strategy had to create leverage against the pressure exerted by the hard-liners who wanted a plea involving severe felonies.

It turned out that the best strategy for the defendant involved two shifts from the approach they had planned as reflected in the data they gave me about themselves. First, the one outside counsel who favored pleading guilty to one lesser felony and numerous misdemeanors needed to convey unity with the rest of the defendant’s team in endorsing a plea to misdemeanors only . Although this one attorney had the right settlement in mind—that was the ultimate agreement on this aspect of the case—he/she could not so much as hint at this flexibility during the initial meetings with the U.S. attorney, and he/she did not.

This attorney acted out the scripted part perfectly. Jack Nicholson, great as his performance was in A Few Good Men , paled in comparison to the performance of the attorney who had to fake a commitment to a position he/she did not really believe in. Since he/she led negotiations on this issue, his/her ability to be convincing was critical, and convincing he/she was.

Of course, getting an attorney or anyone else to act contrary to their beliefs is no small order. It takes great faith that the model’s logic should be allowed to trump personal intuition. As an old client used to say when introducing me to his colleagues, “Check your intuition at the door.” The greatest value of a model is when it provides an insight that is contrary to the decision makers’ expectations—when it correctly urges them to check their intuition at the door. It takes a courageous person to defy one’s own beliefs and follow the lead derived from a computer model, since after all we never know what is or is not correct until after the fact. All we know is the model’s track record for accuracy (but then everyone thinks his problem is unique) and whether the logic for the proposed action is persuasive. Fortunately, in this case the outside attorney being asked to change his/her approach had worked with my firm before on other cases. In fact, this attorney is the very person who persuaded the client to use my company’s services. He/she had seen the model, as he/she put it, “work its magic” before, so this attorney had no problem agreeing to act out the part as written by the model.

Читать дальше