Finally, figure out who you think has the most influence among your friends or family members if you assume that everyone thinks the choice is equally important. Give the person credited as being most persuasive a score of 100 and rate everybody else relative to that. So if Harry is 100 and Jane is 60 and John is 40 in potential clout, and Jane and John want to see The Sound of Music and Harry wants to see A Clockwork Orange , then that means that John and Jane together just offset Harry’s ability to persuade if they all care equally intensely about choosing a movie. If Jane were 60 and John were 70, then, all else being equal, they could persuade Harry to moderate his view and give more consideration to the movie Jane and John prefer. Of course, if someone else supported Harry’s choice, that might create a strong enough coalition to defeat John and Jane. The dynamics get complicated, but the basic idea should be straightforward.

It’s important to note that most of us make these assessments of interests in any situation. We just do such calculations naturally with relative judgments of where people stand on a given issue. What I’ve sketched above is simply a formalization of that natural process—which becomes all the more needed the more complicated the problems in question become.

By now you are probably thinking, Sure, people can fill in numbers to the questions, but it’s just guesswork. Ask two experts the same question and you’ll get two different answers. Guess what—that’s not true. If it were, then there is barely any chance that a model like mine could achieve any consistent accuracy. There would be too much luck involved. In fact, the CIA has checked out the risk that different experts give greatly different answers leading to greatly different predictions. They found little variation in the predictive results from the sort of modeling I do, even when the people asked had dramatically different access to information. Academic experts, for instance, generally do not know the classified information that intelligence analysts have access to. Yet both groups tend to provide data so similar, wherever it’s from, that the results hardly change when moving across these experts. Even more surprisingly, the answers often don’t change much when the inputs for the computer model are put together by undergraduate students with no expertise at all.

Once I was teaching an undergraduate class at the University of Rochester while also investigating how best to get Ferdinand Marcos to resign as head of the Philippine government and create an atmosphere ripe for a free election in that country. William Casey, then Ronald Reagan’s director of intelligence, asked me to study this problem, and I was locked in a (cold) lead-lined vault at CIA headquarters to do it. I had access to classified information, but was not even allowed to read my own report when it was finished. The report was for the eyes of only the president, the vice president, the secretaries of state and defense, the national security adviser, and a few others. Meanwhile, my students worked on the same problem and were given access to the computer program I had developed to help solve such problems. They extracted the required information from magazines such as The Economist and newspapers such as The New York Times and fed their data into the computer. Ninety percent of them arrived at the same conclusions I reached in the lead-lined vault, and those conclusions about strategy proved to work rather well. This should tell us that the information needed to make good predictions is not terribly exotic; it does not require years of learning some other country’s language, history, and culture, although all of that is a big help. It should also tell us that a lot of classified information is easily reproduced from open, public sources for those who are willing to work at it.

Now that we have an idea of where and how to find our information, working out how to get what any given player wants is the key to generating predictions, and ultimately to engineering outcomes. Since everyone involved in a given problem is concerned with getting what they want, their behavior and choices are predictable. Each and every one of them will act so as to lead to the attainable outcome that is closest to what they want, given what they believe about the situation.

What might people’s goals be in a generic sense? Whatever the specific issue, I always operate under the assumption that everyone wants two things when making a decision (although different people weight those two things differently). One thing they want is a decision that is as close as possible to the choice they advocate. The second thing they want is glory—the ego satisfaction that comes from the recognition by others that they played an important part in putting a deal together.

Some people care so much about getting credit for putting an agreement together that they’re willing to shift their position dramatically if that will help promote a deal. Others prefer to go down in a blaze of glory, backing a losing position rather than making concessions that would make a deal feasible. Everyone shares these two goals: get their preferred outcome, and get credit for any outcome. Different people value one or the other differently, and so they’re willing to trade away returns on one dimension to get better returns on the other.

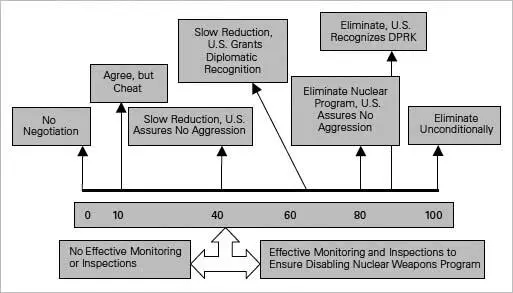

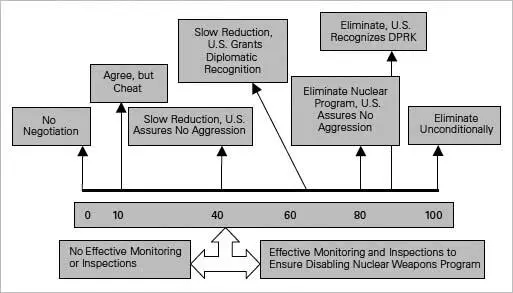

Let’s return to the North Koreans. After interviewing experts and compiling research, we know three important pieces of information about each player: what they say they want, how much they care, and how influential they can be. In the case of North Korea, the range of policy choices is depicted in figure 4.1, both in terms of substantive meaning and numerical value. (One easy way to get numbers out of policy stances is to ask experts to make marks on a line for several policy options, emphasizing that they should be spaced to reflect how close or distant the choices are substantively from each other. Then a ruler can be used to measure the distances, and voilà, a simple numeric scale has been created.)

My 2004 study of North Korea identified more than fifty players in this complicated international game. Two, Kim Jong Il and George W. Bush, had a veto, which meant that no deal could be struck without their support. Kim Jong Il’s preferred position was to agree to a deal but to structure it so that he could cheat later, reneging on his promises (10 on the scale). According to the experts, Bush wanted the unconditional elimination of North Korea’s nuclear program (100 on the scale). Without some strategizing, then, the two sides were unlikely to reach agreement, since the two most important decision makers were miles apart and both were thought to be reluctant compromisers. Yet a first approximation of the likely outcome suggested strong support for a consequential reduction in North Korea’s nuclear capabilities accompanied by significant U.S. concessions, including security guarantees for North Korea and considerable foreign economic assistance. How did I arrive at that inference?

FIG. 4.1. North Korean Issue

The information collected about each player in the North Korea game—their position on the issue, their salience for the issue, and the clout they could bring to bear—allows us to see how much power there is behind each possible outcome. Potential influence, one of the three pieces of information, tells us how persuasive each player could be, but not how persuasive each is. That depends on their willingness to apply their influence to the problem, and that in turn is determined by how salient the issue is. So we can define a player’s power—the pressure they really exert to shape the outcome—as equal to their influence multiplied by their salience.

Читать дальше