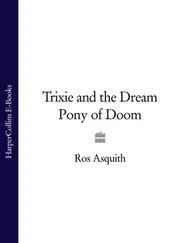

A Cossack sea-going koch.

Other Cossacks, travelling in the same manner in similar boats, traversed the Arctic Ocean by hugging the northern coast of Siberia and reached the Pacific by sea in 1648. Semyon Dezhnev, a Cossack from Veliky Ustug, had assembled seven snub-nosed square-sailed riverboats known as kochi , each crewed by up to nineteen men. Sailing east in search of sable his expedition rounded what is today known as the Bering Strait, passed between Little and Big Diomede Islands – the modern-day border between Russia and the USA – and founded an ostrog at Anadyr on the Chukchi peninsula. Four of his boats were lost, along with sixty-four out of his eighty-nine men. Undaunted, Dezhnev returned later with a new expedition, discovered a portage through the tributaries of the Kolyma River to the Sea of Okhotsk, from where he sailed as far as the border of the Chinese empire on the Amur River in 1650.18

News of the explorations of Russian travellers was greeted with keen interest in Western Europe. The Dutch trader Nicolaas Witsen, one of the first Europeans to travel in Siberia and thirteen times mayor of Amsterdam, incorporated Dezhnev’s observations into the groundbreaking world map he produced in 1690 alongside his encyclopedic study of the Russian Empire, Noord en Oost Tartarye . Unfortunately for Russian navigators, however, Dezhnev’s discoveries remained virtually unknown in his home country. The only extant copy of his official report19 was buried in an archive in Yakutsk until discovered in the 1730s.20

Peter the Great may not have been aware that his countrymen had already succeeded in rounding Russia’s eastern extremity, but his twin enthusiasms were seafaring and the expansion of the Russian Empire, and the exploration of Eurasia was a lifelong interest. In Siberia, and what lay beyond, Peter met a challenge vast enough for his ambition. In 1681, when Peter was nine, one of his father’s final acts was to order a royal fort built at the Cossack ostrog of Okhotsk, the first Russian settlement on the Pacific.21 In 1711 Peter ordered a naval wharf built at Okhotsk – an optimistic move, for there were as yet no Russian naval ships on the Pacific to use it.22 Peter fantasized about trade missions to China, Japan and India and of extending Russian sovereignty over the North American coast from the Bering Strait to the Spanish empire. But it was not until 1724, when Peter was already dying, that he finally commissioned Vitus Bering, a Dane with twenty years’ service in his navy, to explore the ‘Eastern Ocean’, Russia’s final frontier.

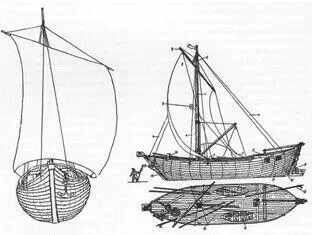

There being no Russian ships sturdy or fast enough to make the round-the-world journey, Bering and thirty-four officers, shipbuilders and workmen set off across Siberia to build their own craft when they arrived at the Pacific. It took the party over two years to drag their tools and equipment such as anchors and cordage across eleven modern-day time zones to the Kamchatka peninsula. There, with the help of workmen and sailors they had picked up on their way, they built the three-masted barque Arkhangel Gavriil . Bering set off across the Pacific in 1728. He mapped parts of the Bering Strait and the north-eastern corner of Russia in some detail, but, to the frustration of St Petersburg, failed to find the ‘great land’ beyond, which had been appearing on Cossack seafarers’ primitive maps since 1710.

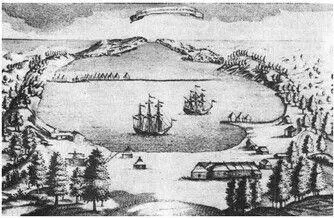

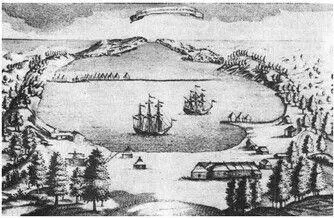

Bering was sent off again in 1733 on a more ambitious two-ship expedition along the same gruelling route. His men, who now included naturalists and scientists, built the barques Svyatoi Pyotr and Svyatoi Pavel on the shores of one of the world’s greatest natural harbours, Avacha Bay on Kamchatka, which they named Petro-Pavlovsk after their vessels. Stepan Krasheninnikov, a young botanist who became the expedition’s chronicler, found the natives of Kamchatka unusually degenerate and disgusting even by Siberian standards. They ‘eat their own lice and wash in urine . . . share their food with their dogs and smell of fish’, Krashennenikov reported. They also ‘cannot count beyond three without using their fingers’.23

View of Avacha Bay and the settlement of Petropavlovsk of Kamchatka, 1740.

This time the expedition made landfall in America. Bering’s first officer, Alexei Chirikov, aboard the Sv. Pavel , almost certainly hove to just south of Jakobi Island, near the modern-day Alaska–Canada border. Chirikov dispatched a longboat to explore the shore, but it never returned. Nor did a smaller jolly boat sent to search for it. Both were probably lost in the tidal undertow that even today makes the Jakobi Channel extremely treacherous.24 Fires were seen ashore and a native canoe briefly emerged and signalled to Chirikov, but he had no boats left to follow it.* After several days’ fruitless waiting he had no choice but to abandon any possible survivors to their fate and turn for home.25 More serious even than the disappearance of fifteen men was the loss of both the Sv. Pavel ’s boats. Without them the ship could take on neither supplies nor water. During his return journey Chirikov had to exchange valuable knives for bladders full of fresh water brought out to the ship in canoes by Aleut islanders.

Bering was even less lucky. Separated from Chirikov’s ship early in the voyage, Bering’s brig the Sv. Pyotr cruised along the American coast, spotting Mount St Elias near modern Yakutat. But he was unable to make it back to Kamchatka before the end of the sailing season and was forced by contrary winds to winter on the island which today bears his name. The ship dragged its too-small anchor in a storm and was wrecked. That winter the sixty-year-old Bering died, probably of heart failure,26 along with thirty-one of his seventy-five men, who mostly perished of scurvy.27 The survivors, including the German naturalist Georg Steller, lived on the meat of the giant slow-moving sea mammals Steller named sea cows. A full-grown specimen weighed nearly 7,000 pounds and could feed the entire crew for a month.28 In the spring of 1742, nine years after they had set out from St Petersburg, the remaining members of the expedition built a smaller boat from the salvaged wreckage of the Sv. Pyotr and limped back across the short distance remaining to Petropavlovsk. Bering’s party had spent the winter just four days’ sail away from salvation.

Despite its high death toll, the second Bering expedition marked a breakthrough for Russian expansion to the New World – not least because in Russian eyes Chirikov had made the land Russian by right of first discovery. Chirikov was not the first European to explore the northern Pacific coast of America – that honour goes to the Elizabethan privateer Sir Francis Drake, who sailed up the coast as far as San Francisco in his ship the Golden Hind during his 1577–80 round-the-world voyage. But Chirikov was the first navigator of modern times to record a landing on the coast, albeit a disastrous one, and had thereby staked a claim to the New World in Russian blood.

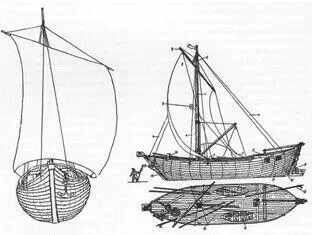

But like the conquest of Siberia, it was not state ambition but private enterprise that drove Russians forward towards America. Word of Steller’s descriptions of islands full of fur seals spread quickly across Siberia. Over the next decade over thirty groups of Cossack explorer-adventurers visited the Aleutian Islands, sailing in forty-foot shtitik boats – single-masted square-sailed vessels of archaic design – out of Okhotsk and Petropavlovsk. For the crews who returned from these two- or three-year fur expeditions the profits were vast. One merchant returned from the Aleutians in 1754 with the pelts of 1,662 sea otters, 840 fur seals and 720 foxes. For the natives, however, the consequences of Russian violence, disease and the depletion of their fragile fishing grounds were devastating. Vladimir Atlasov, an early Cossack explorer of Kamchatka, reported a population of two to three thousand adult males on the peninsula in the 1730s. By the first official census in 1773 only 706 souls remained.29

Читать дальше