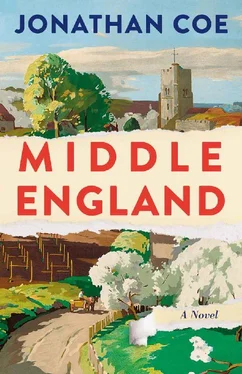

Джонатан Коу - Middle England

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джонатан Коу - Middle England» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Penguin Books Ltd, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Middle England

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books Ltd

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:9780241981320

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Middle England: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Middle England»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Middle England — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Middle England», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jonathan Coe

MIDDLE ENGLAND

Contents

Merrie England

Deep England

Old England

Author’s Note

Follow Penguin

By the same author

FICTION

The Accidental Woman A Touch of Love The Dwarves of Death What a Carve Up!

The House of Sleep The Rotters’ Club The Closed Circle The Rain Before It Falls The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim Expo 58

Number 11

The Broken Mirror

NON-FICTION

Like a Fiery Elephant: The Story of B. S. Johnson

For Janine, Matilda and Madeline

MERRIE ENGLAND

‘In the century’s last decades, “British” as a self-description began to offer something else … It had room for newcomers from abroad and for people like me who found its capaciousness and slackness attractive. Here was a civic nationalism that meandered pleasantly like an old river, its dangerous force spent far upstream.’

Ian Jack, Guardian , 22 October 2016

1.

April 2010

The funeral was over. The reception was starting to fizzle out. Benjamin decided it was time to go.

‘Dad?’ he said. ‘I think I’m going to make a move.’

‘Good,’ said Colin. ‘I’ll come with you.’

They headed for the door and managed to escape without saying any goodbyes. The village street was deserted, silent in the late sunshine.

‘We shouldn’t really just leave like this,’ said Benjamin, glancing back towards the pub doubtfully.

‘Why not? I’ve spoken to everyone I want to. Come on, take me to the car.’

Benjamin allowed his father to hold him by the arm in a faltering grip. He was steadier on his feet that way. With indescribable slowness, they began to shuffle along the street towards the pub car park.

‘I don’t want to go home,’ said Colin. ‘I can’t face it, without her. Take me to your place.’

‘Sure,’ said Benjamin, even as his heart plummeted. The vision he had been promising himself – solitude, meditation, a cold glass of cider at the old wrought-iron table, the murmur of the river as it rippled by on its timeless course – disappeared, spiralled away into the afternoon sky. Never mind. His duty today was to his father. ‘Would you like to stay the night?’

‘Yes, I would,’ said Colin, but he didn’t say thank you. He rarely did, these days.

*

The traffic was heavy, and the drive to Benjamin’s house took almost an hour and a half. They drove through the heart of Middle England, more or less following the course of the River Severn, through the towns of Bridgnorth, Alveley, Quatt, Much Wenlock and Cressage, a placid, unmemorable journey where the only punctuation marks were petrol stations, pubs and garden centres, while brown heritage signs dangled the more distant temptations of wildlife centres, National Trust houses and arboretums in front of the bored traveller. The entrance to each village was marked not only by the sign announcing its name, but by a flashing reminder of the speed at which Benjamin was driving, and a warning notice telling him to slow down.

‘They’re a nightmare, aren’t they, these speed traps?’ Colin said. ‘The buggers are out to get money from you every step of the way.’

‘Prevents accidents, I suppose,’ said Benjamin.

His father grunted sceptically.

Benjamin turned on the radio, tuned as usual to Radio Three. He was in luck: the slow movement of Fauré’s Piano Trio. The melancholy, unassuming contours of the melody not only seemed a fitting accompaniment to the memories of his mother that were filling his mind today (and, presumably, Colin’s), but also seemed to mirror, in sound, the gentle curves of the road, and even the muted greens of the landscape through which it carried them. The fact that the music was recognizably French made no difference: there was a commonality here, a shared spirit. Benjamin felt utterly at home in this music.

‘Turn that racket off, can’t you?’ Colin said. ‘Can’t we listen to the news?’

Benjamin let the last thirty or forty seconds of the movement play out, then switched to Radio Four. It was the PM programme and immediately they were plunged into a familiar world of gladiatorial combat between interviewer and politician. In one week’s time there would be a general election. Colin would vote Conservative, as he had done in every British election since 1950, and Benjamin, as usual, was undecided, except in the sense that he had decided not to vote. Nothing they were likely to hear on the radio in the next seven days would make any difference. Today’s big story seemed to be that the prime minister, Gordon Brown, fighting for re-election, had been caught on microphone describing a potential supporter as ‘a sort of bigoted woman’, and the media were making the most of it.

‘The prime minister has shown his true colours,’ a Conservative MP was saying, gleefully. ‘Anyone who expresses these legitimate concerns is simply a bigot, in his view. And that’s why we can never have a serious debate about immigration in this country.’

‘But isn’t it true that Mr Cameron, your own leader, is every bit as reluctant –’

Benjamin turned the radio off without explanation. For a while they drove in silence.

‘She couldn’t stand politicians,’ Colin said, bringing some subterranean train of thought to the surface, and not needing to specify who he meant by ‘she’. He spoke in a low voice, thick with regret and repressed emotion. ‘Thought they were all as bad as each other. All on the fiddle, every one of them. Fiddling their expenses, not declaring their interests, holding down half a dozen jobs on the side …’

Benjamin nodded, while remembering that in fact it was Colin himself, not his late wife, who was obsessed with the venality of politicians. It was one of the few subjects on which this habitually taciturn man could become talkative, and perhaps it would be better to let this happen now, to stop him from being distressed by more painful thoughts. But Benjamin rebelled against the idea. Today they had bid farewell to his mother, and he wasn’t going to let the sanctity of that occasion be tarnished by one of his father’s rants.

‘What I always liked about Mum, though,’ he said, by way of diversion, ‘was that she never sounded bitter about stuff like that. You know, if she disapproved of something, it didn’t make her angry, it just made her sort of … sad.’

‘Yes, she was a gentle soul,’ Colin agreed. ‘One of the best.’ He said no more than that, but after a few seconds took a grimy-looking handkerchief out of his trouser pocket and wiped both eyes with it, slowly and carefully.

‘It’s going to be weird for you,’ said Benjamin, ‘being by yourself. But I know you’ll manage. I’m sure of it.’

Colin stared into space. ‘Fifty-five years, we were together …’

‘I know, Dad. It’s going to be tough. But Lois will be close by, a lot of the time. And I’m not far away either. Not really.’

They drove on.

*

Benjamin lived in a converted mill house on the banks of the River Severn, on the outskirts of a village just north-east of Shrewsbury. The house was approached down a single-track road, overhung with trees, its hedgerows densely overgrown on either side. He had moved to this absurdly remote and secluded spot at the beginning of the year, the sale of his two-bedroom flat in Belsize Park having funded the purchase, with enough capital left over to support his modest lifestyle for a few years to come. The house was far too big for a single man, but then he had not been single when he had bought it. There were four bedrooms, two sitting rooms, a dining room, a large open-plan kitchen complete with Aga and a study with generous leaded windows overlooking the river. So far Benjamin had been extremely happy there, dispelling his friends’ and family’s early suspicions that he had made a terrible mistake.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Middle England»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Middle England» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Middle England» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.