.00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000138.

By displaying this number in all its multi-zeroed glory, Greene impresses upon us the fact that it is very small yet oddly precise. He then points out that it is hard to explain that value because it seems to be fine-tuned to allow life on earth to come into being:

In universes with larger amounts of dark energy, whenever matter tries to clump into galaxies, the repulsive push of the dark energy is so strong that the clump gets blown apart, thwarting galactic formation. In universes whose dark-energy value is much smaller, the repulsive push changes to an attractive pull, causing those universes to collapse back on themselves so quickly that again galaxies wouldn’t form. And without galaxies, there are no stars, no planets, and so in those universes there’s no chance for our form of life to exist.

To the rescue comes an idea which (Greene showed us earlier) explained the bang in the big bang. According to the theory of inflationary cosmology, empty space can spawn other big bangs, creating a vast number of other universes: a multiverse. This makes the precise value of dark energy in our universe less surprising:

We find ourselves in this universe and not another for much the same reason we find ourselves on earth and not on Neptune—we find ourselves where conditions are ripe for our form of life.

Of course! As long as there are many planets, one of them is likely to be at a hospitable distance from the sun, and no one thinks it’s sensible to ask why we find ourselves on that planet rather than on Neptune. So it would be if there are many universes.

But scientists still faced a problem, which Greene illustrates with an analogy:

Just as it takes a well-stocked shoe store to guarantee you’ll find your size, only a well-stocked multiverse can guarantee that our universe, with its peculiar amount of dark energy, will be represented. On its own, inflationary cosmology falls short of the mark. While its never-ending series of big bangs would yield an immense collection of universes, many would have similar features, like a shoe store with stacks and stacks of sizes 5 and 13, but nothing in the size you seek.

The piece that completes the puzzle is string theory, according to which “the tally of possible universes stands at the almost incomprehensible 10 500, a number so large it defies analogy.”

By combining inflationary cosmology and string theory, … the stock room of universes overflows: in the hands of inflation, string theory’s enormously diverse collection of possible universes become actual universes, brought to life by one big bang after another. Our universe is then virtually guaranteed to be among them. And because of the special features necessary for our form of life, that’s the universe we inhabit.

In just three thousand words, Greene has caused us to understand a mind-boggling idea, with no apology that the physics and math behind the theory might be hard for him to explain or for readers to understand. He narrates a series of events with the confidence that anyone looking at them will know what they imply, because the examples he has chosen are exact. Division by zero is a perfect example of “equations breaking down”; gravity tugs at a tossed ball in exactly the way it slows cosmic expansion; the improbability of finding a precisely specified item in a small pool of possibilities applies to both the sizes of shoes in a store and the values of physical constants in a multiverse. The examples are not so much metaphors or analogies as they are actual instances of the phenomena he is explaining, and they are instances that readers can see with their own eyes. This is classic style.

It may not be a coincidence that Greene, like many scientists since Galileo, is a lucid expositor of difficult ideas, because the ideal of classic prose is congenial to the worldview of the scientist. Contrary to the common misunderstanding in which Einstein proved that everything is relative and Heisenberg proved that observers always affect what they observe, most scientists believe that there are objective truths about the world and that they can be discovered by a disinterested observer.

By the same token, the guiding image of classic prose could not be further from the worldview of relativist academic ideologies such as postmodernism, poststructuralism, and literary Marxism. And not coincidentally, it was scholars with these worldviews who consistently won the annual Bad Writing Contest, a publicity stunt held by the philosopher Denis Dutton during the late 1990s. 8First place in 1997 went to the eminent critic Fredric Jameson for the opening sentence of his book on film criticism:

The visual is essentially pornographic, which is to say that it has its end in rapt, mindless fascination; thinking about its attributes becomes an adjunct to that, if it is unwilling to betray its object; while the most austere films necessarily draw their energy from the attempt to repress their own excess (rather than from the more thankless effort to discipline the viewer).

The assertion that “the visual is essentially pornographic” is not, to put it mildly, a fact about the world that anyone can see. The phrase “which is to say” promises an explanation, but it is just as baffling: can’t something have “its end in rapt, mindless fascination” without being pornographic? The puzzled reader is put on notice that her ability to understand the world counts for nothing; her role is to behold the enigmatic pronouncements of the great scholar. Classic writing, with its assumption of equality between writer and reader, makes the reader feel like a genius. Bad writing makes the reader feel like a dunce.

The winning entry for 1998, by another eminent critic, Judith Butler, is also a defiant repudiation of classic style:

The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.

A reader of this intimidating passage can marvel at Butler’s ability to juggle abstract propositions about still more abstract propositions, with no real-world referent in sight. We have a move from an account of an understanding to a view with a rearticulation of a question, which reminds me of the Hollywood party in Annie Hall where a movie producer is overheard saying, “Right now it’s only a notion, but I think I can get money to make it into a concept, and later turn it into an idea.” What the reader cannot do is understand it—to see with her own eyes what Butler is seeing. Insofar as the passage has a meaning at all, it seems to be that some scholars have come to realize that power can change over time.

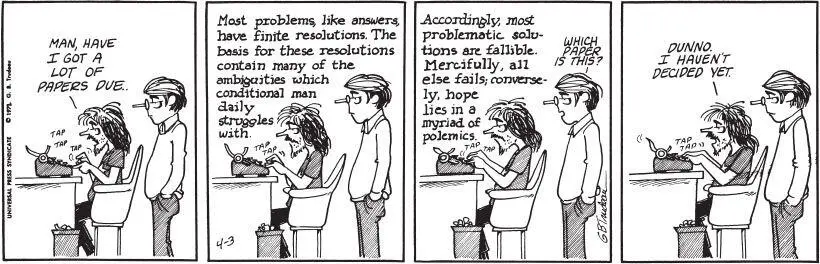

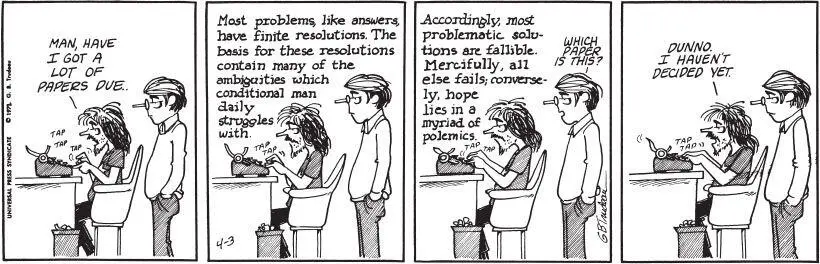

The abstruseness of the contest winners’ writing is deceptive. Most academics can effortlessly dispense this kind of sludge, and many students, like Zonker Harris in this Doonesbury cartoon, acquire the skill without having to be taught:

Doonesbury © 1972 g. b. trudeau. Reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.

Just as deceptive is the plain language of Greene’s explanation of the multiverse. It takes cognitive toil and literary dexterity to pare an argument to its essentials, narrate it in an orderly sequence, and illustrate it with analogies that are both familiar and accurate. As Dolly Parton said, “You wouldn’t believe how much it costs to look this cheap.”

Читать дальше