–er and –est; more and most. Adjectives can be inflected for degree, giving us comparatives ( harder, better, faster, stronger ) and superlatives ( hardest, best, fastest, strongest ). Tradition says that you should reserve the comparative for two things and use the superlative for more than two: you should refer to the faster of the two runners, rather than the fastest, but it’s all right to refer to the fastest of three runners. The same is true for polysyllabic adjectives that shun –er and – est in favor of more and most: the more intelligent of the two; the most intelligent of the three. But it’s not a hard-and-fast rule: we say May the best team win, not the better team, and Put your best foot forward, not your better foot. Once again the traditional rule is stated too crudely. It’s not the sheer number of items that determines the choice but the manner in which they are being compared. A comparative adjective is appropriate when the two items are being directly contrasted, one against the other; a superlative can work when an item is superior not just to the alternative in view at the time but to a larger implicit comparison group. If Usain Bolt and I happened to be competing for a spot on an Olympic Dream Team, it would be misleading to say that they picked the faster of the two men for the team; they picked the fastest man.

things and stuff (count nouns, mass nouns and ten items or less ).Finally, let’s turn to the pebbles and gravel, which represent the two ways that English speakers can conceptualize aggregates: as discrete things, which are expressed as plural count nouns, and as continuous substances, which are expressed as mass nouns. Some quantifiers are choosy as to which they apply to. We can talk about many pebbles but not much pebbles, much gravel but not many gravel. Some quantifiers are not choosy: We can talk about more pebbles or more gravel. 44

Now, you might think that if more can be used with both count and mass nouns, so can less . But it doesn’t work that way: you may have less gravel, but most writers agree that you can only have fewer pebbles, not less pebbles. This is a reasonable distinction, but purists have extended it with a vengeance. The sign over supermarket express checkout lanes, TEN ITEMS OR LESS, is a grammatical error, they say, and as a result of their carping whole-food and other upscale supermarkets have replaced the signs with TEN ITEMS OR FEWER. The director of the Bicycle Transportation Alliance has apologized for his organization’s popular T-shirt that reads ONE LESS CAR, conceding that it should read ONE FEWER CAR. By this logic, liquor stores should refuse to sell beer to customers who are fewer than twenty-one years old, law-abiding motorists should drive at fewer than seventy miles an hour, and the poverty line should be defined by those who make fewer than eleven thousand five hundred dollars a year. And once you master this distinction, well, that’s one fewer thing for you to worry about. 45

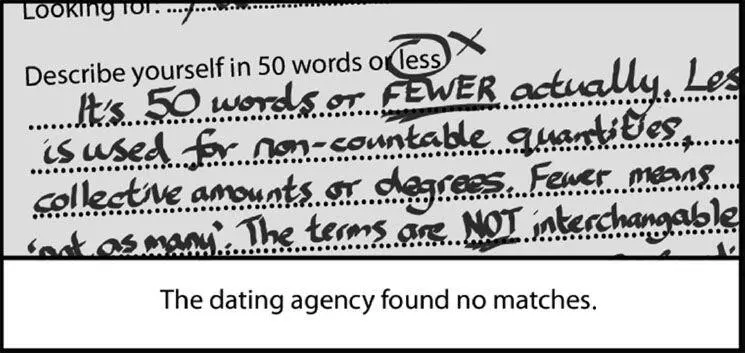

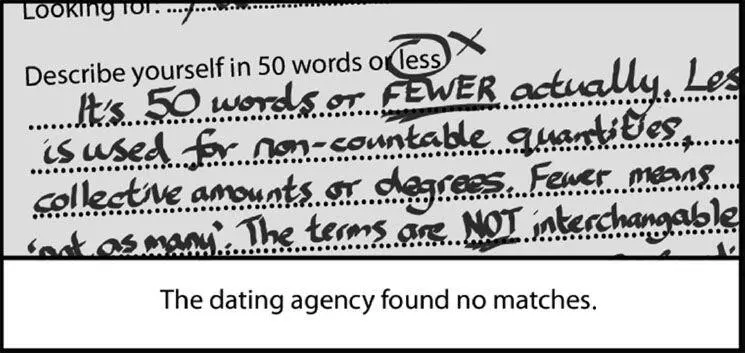

If this is all starting to sound weird to you, you’re not alone. The caption of this cartoon reminds us that while sloppy grammar can be a turnoff, so can the kind of pedantry that takes a grammatical distinction too far:

© luke surl 2008

What’s going on? As many linguists have pointed out, the purists have botched the less-fewer distinction. It is certainly true that less is clumsy when applied to the plurals of count nouns for discrete items: fewer pebbles really does sound better than less pebbles. But it’s not true that less is forbidden to apply to count nouns across the board. Less is perfectly natural with a singular count noun, as in one less car and one less thing to worry about. It’s also natural when the entity being quantified is a continuous extent and the count noun refers to units of measurement. After all, six inches, six months, six miles, and a bill for six dollars don’t actually correspond to six hunks of matter; the units, like the 1–11 scale on Nigel Tufnel’s favorite amplifier in This Is Spinal Tap, are arbitrary. In these cases less is natural and fewer is a hypercorrection. And less is idiomatic in certain expressions in which a quantity is being compared to a standard, including He made no less than fifteen mistakes and Describe yourself in fifty words or less. Nor are these idioms recent corruptions: for much of the history of the English language, less could be used with both count and mass nouns, just as more is today.

Like many dubious rules of usage, the less-fewer distinction has a smidgen of validity as a pointer of style. In cases where less and fewer are both available to a writer, such as Less/fewer than twenty of the students voted, the word fewer is the better choice in classic style because it enhances vividness and concreteness. But that does not mean that less is a grammatical error.

The same kind of judgment applies to the choice between over and more than. When the plural refers to countable objects, it’s a good idea to use more than. He owns more than a hundred pairs of boots is more classic-stylish than He owns over a hundred pairs of boots, because it encourages us to imagine the pairs individually rather than lumping them together as an amorphous collection. But when the plural defines a point on a scale of measurement, as in These rocks are over five million years old, it’s perverse to insist that it can only be more than five million years old, because no one is counting the years one by one. In neither of these cases, usage guides agree, is over a grammatical error.

I can’t resist the temptation to sum up this review with a short story by the writer Lawrence Bush (reproduced with his kind permission), which alludes to many of the points of usage we have examined (see how many you can spot) while speaking to the claim that the traditional rules reduce misunderstanding: 46

I had only just arrived at the club when I bumped into Roger. After we had exchanged a few pleasantries, he lowered his voice and asked, “What do you think of Martha and I as a potential twosome?”

“That,” I replied, “would be a mistake. Martha and me is more like it.”

“You’re interested in Martha?”

“I’m interested in clear communication.”

“Fair enough,” he agreed. “May the best man win.” Then he sighed. “Here I thought we had a clear path to becoming a very unique couple.”

“You couldn’t be a very unique couple, Roger.”

“Oh? And why is that?”

“Martha couldn’t be a little pregnant, could she?”

“Say what? You think that Martha and me …”

“Martha and I.”

“Oh.” Roger blushed and set down his drink. “Gee, I didn’t know.”

“Of course you didn’t,” I assured him. “Most people don’t.”

“I feel very badly about this.”

“You shouldn’t say that: I feel bad …”

“Please, don’t,” Roger said. “If anyone’s at fault here, it’s me.”

masculine and feminine (nonsexist language and singular they ). In a 2013 press release President Barack Obama praised a Supreme Court decision striking down a discriminatory law with the sentence “No American should ever live under a cloud of suspicion just because of what they look like.” 47In doing so he touched one of the hottest usage buttons of the past forty years: the use of the plural pronouns they, them, their, and themselves with a grammatically singular antecedent like no American. Why didn’t the president write because of what he looks like, or because of what he or she looks like ?

Читать дальше