English syntax demands subject before object. Human memory demands light before heavy. Human comprehension demands topic before comment and given before new. How can a writer reconcile these irreconcilable demands about where the words should go in a sentence?

Necessity is the mother of invention, and over the centuries the English language has developed workarounds for its rigid syntax. They consist of alternative constructions that are more or less synonymous but that place the participants in different positions in the left-to-right ordering of the string, which means they appear at different times in the early-to-late processing in a reader’s mind. Fluent writers have these constructions at their fingertips to simultaneously control the content of a sentence and the sequencing of its words.

Foremost among them is the unfairly maligned passive voice: Laius was killed by Oedipus, as opposed to Oedipus killed Laius. In chapter 2 we saw one of the benefits of the passive, namely that the agent of the event, expressed in the by- phrase, can go unmentioned. This is handy for mistake-makers who are trying to keep their names out of the spotlight and for narrators who want you to know that helicopters were used to put out some fires but don’t think you need to know that it was a guy named Bob who flew one of the helicopters. Now we see the other major benefit of the passive: it allows the doer to be mentioned later in the sentence than the done-to. That comes in handy in implementing the two principles of composition when they would otherwise be stymied by the rigid word order of English. The passive allows a writer to postpone the mention of a doer that is heavy, old news, or both. Let’s look at how this works.

Consider this passage from the Wikipedia entry for Oedipus Rex, which (spoiler alert) reveals the terrible truth about Oedipus’s parentage.

A man arrives from Corinth with the message that Oedipus’s father has died. … It emerges that this messenger was formerly a shepherd on Mount Cithaeron, and that he was given a baby. … The baby, he says, was given to him by another shepherd from the Laius household, who had been told to get rid of the child.

It contains three passives in quick succession ( was given a baby; was given to him; had been told ), and for good reason. First we are introduced to a messenger; all eyes are upon him. If he figures in any subsequent news, he should be mentioned first. And so he is, thanks to the passive voice, even though the news does not involve his doing anything: He (old information) was given a baby (new information).

Now that we’ve been introduced to a baby, the baby is on our minds. If there’s anything new to say about him, the news should begin with a mention of that baby. Once again the passive voice makes that possible, even though the baby didn’t do anything: The baby, he says, was given to him by another shepherd. The shepherd in question is not just newsworthy but also heavy: he is being singled out with the big, hairy phrase another shepherd from the Laius household, who had been told to get rid of the child. That’s a lot of verbiage for a reader to handle while figuring out the syntax of the sentence, but the passive voice allows it to come at the end, when all of the reader’s other work is done.

Now imagine that an editor mindlessly followed the common advice to avoid the passive and altered the passage accordingly:

A man arrives from Corinth with the message that Oedipus’s father has died. … It emerges that this messenger was formerly a shepherd on Mount Cithaeron, and that someone gave him a baby. … Another shepherd from the Laius household, he says, whom someone had told to get rid of the child, gave the baby to him.

Active, shmactive! This is what happens when a heavy phrase with new information is forced into the beginning of a sentence just because it happens to be the agent of the action and that’s the only place an active sentence will let it appear.

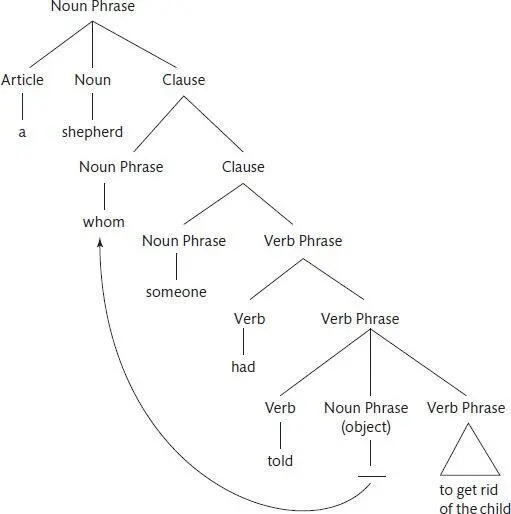

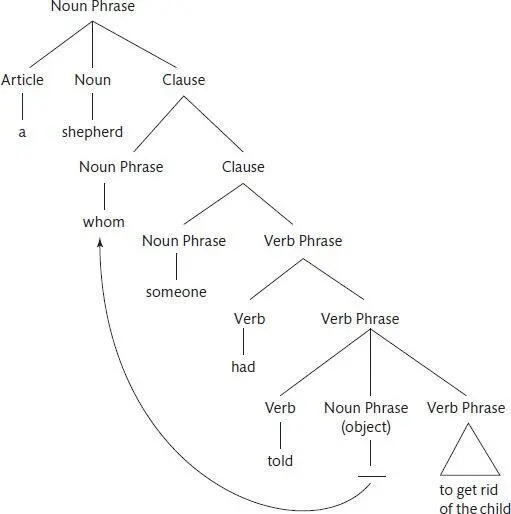

The original passage had a third passive— who had been told to get rid of the child— which the copy editor of my nightmares has also turned into an active: whom someone had told to get rid of the child. This highlights yet another payoff of the passive voice: it can unburden memory by shortening the interval between a filler and a gap. When an item is modified by a relative clause, and its role inside the clause is the object of the verb, the reader is faced with a long span between the filler and the gap. 34Look at the tree immediately below, which has a relative clause in the active voice:

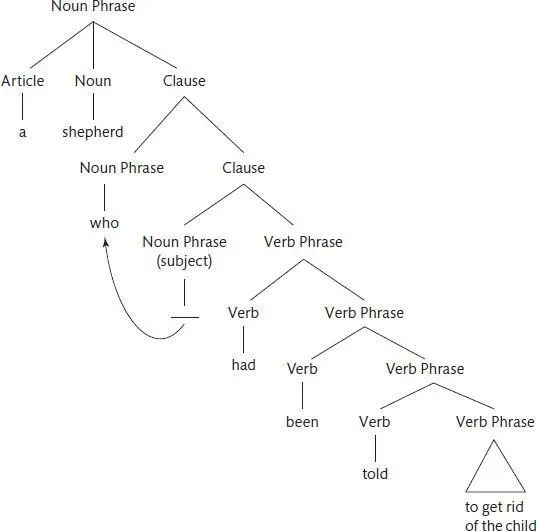

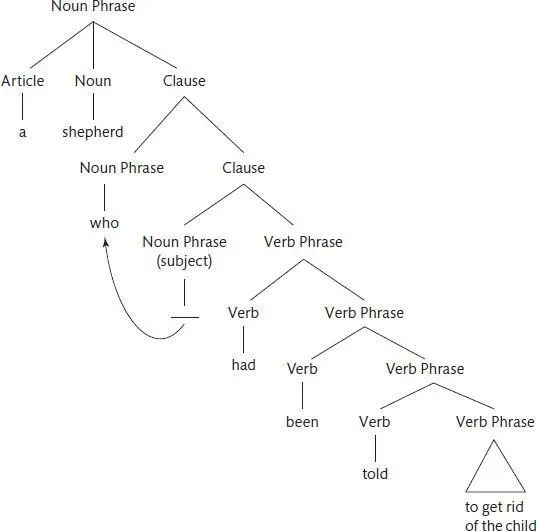

You can see a long arrow between the filler whom and the gap after told, which spans three words and three newly introduced phrases. That’s the material a reader must hold in mind between the time she encounters whom and the time she can figure out what the whom is doing. Now look at the second tree, where the relative clause has been put in the passive. A puny arrow connects the filler who with a gap right next door, and the reader gets instant gratification: no sooner does she come across who than she knows what it’s doing. True, the passive phrase itself is heavier than the active, with four levels of branching rather than three, but it comes at the end, where there’s nothing else to keep track of. That’s why well-written prose puts object relative clauses in the passive voice, and difficult prose keeps them in the active voice, like this:

Among those called to the meeting was Mohamed ElBaradei, the former United Nations diplomat protesters demanding Mr. Morsi’s ouster have tapped __ as one of their negotiators over a new interim government, Reuters reported, citing unnamed official sources.

This sentence is encumbered, among other things, by a long stretch between the filler of the relative clause, the former United Nations diplomat, and the gap after tapped seven words later. Though the sentence may be beyond salvation, passivizing the relative clause would be a place to start: the former United Nations diplomat who has been tapped by protesters demanding Mr. Morsi’s ouster.

The passive voice is just one of the gadgets that the English language makes available to rearrange phrases while preserving their semantic roles. Here are a few others that are handy when the need arises to separate illicit neighbors, to place old information before new, to put fillers close to their gaps, or to save the heaviest for last: 35

Basic order:

Preposing:

Oedipus met Laius on the road to Thebes.

On the road to Thebes, Oedipus met Laius.

Basic order:

Postposing:

The servant left the baby whom Laius had condemned to die on the mountaintop.

The servant left on the mountaintop the baby whom Laius had condemned to die.

Double-object dative:

Prepositional dative:

Jocasta handed her servant the infant.

Jocasta handed the infant to her servant.

Basic construction:

Читать дальше