Calvin and Hobbes © 1993 Watterson. Reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.

I have long been skeptical of the bamboozlement theory, because in my experience it does not ring true. I know many scholars who have nothing to hide and no need to impress. They do groundbreaking work on important subjects, reason well about clear ideas, and are honest, down-to-earth people, the kind you’d enjoy having a beer with. Still, their writing stinks.

People often tell me that academics have no choice but to write badly because the gatekeepers of journals and university presses insist on ponderous language as proof of one’s seriousness. This has not been my experience, and it turns out to be a myth. In Stylish Academic Writing (no, it is not one of the world’s thinnest books), Helen Sword masochistically analyzed the literary style in a sample of five hundred articles in academic journals, and found that a healthy minority in every field were written with grace and verve. 1

In explaining any human shortcoming, the first tool I reach for is Hanlon’s Razor: Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. 2The kind of stupidity I have in mind has nothing to do with ignorance or low IQ; in fact, it’s often the brightest and best informed who suffer the most from it. I once attended a lecture on biology addressed to a large general audience at a conference on technology, entertainment, and design. The lecture was also being filmed for distribution over the Internet to millions of other laypeople. The speaker was an eminent biologist who had been invited to explain his recent breakthrough in the structure of DNA. He launched into a jargon-packed technical presentation that was geared to his fellow molecular biologists, and it was immediately apparent to everyone in the room that none of them understood a word. Apparent to everyone, that is, except the eminent biologist. When the host interrupted and asked him to explain the work more clearly, he seemed genuinely surprised and not a little annoyed. This is the kind of stupidity I am talking about.

Call it the Curse of Knowledge: a difficulty in imagining what it is like for someone else not to know something that you know. The term was invented by economists to help explain why people are not as shrewd in bargaining as they could be, in theory, when they possess information that their opposite number does not. 3A used-car dealer, for example, should price a lemon at the same value as a creampuff of the same make and model, because customers have no way to tell the difference. (In this kind of analysis, economists imagine that everyone is an amoral profit-maximizer, so no one does anything just for honesty’s sake.) But at least in experimental markets, sellers don’t take full advantage of their private knowledge. They price their assets as if their customers knew as much about their quality as they do.

The curse of knowledge is far more than a curiosity in economic theory. The inability to set aside something that you know but that someone else does not know is such a pervasive affliction of the human mind that psychologists keep discovering related versions of it and giving it new names. There is egocentrism, the inability of children to imagine a simple scene, such as three toy mountains on a tabletop, from another person’s vantage point. 4There’s hindsight bias, the tendency of people to think that an outcome they happen to know, such as the confirmation of a disease diagnosis or the outcome of a war, should have been obvious to someone who had to make a prediction about it before the fact. 5There’s false consensus, in which people who make a touchy personal decision (like agreeing to help an experimenter by wearing a sandwich board around campus with the word REPENT) assume that everyone else would make the same decision. 6There’s illusory transparency, in which observers who privately know the backstory to a conversation and thus can tell that a speaker is being sarcastic assume that the speaker’s naïve listeners can somehow detect the sarcasm, too. 7And there’s mindblindness, a failure to mentalize, or a lack of a theory of mind, in which a three-year-old who sees a toy being hidden while a second child is out of the room assumes that the other child will look for it in its actual location rather than where she last saw it. 8(In a related demonstration, a child comes into the lab, opens a candy box, and is surprised to find pencils in it. Not only does the child think that another child entering the lab will know it contains pencils, but the child will say that he himself knew it contained pencils all along!) Children mostly outgrow the inability to separate their own knowledge from someone else’s, but not entirely. Even adults slightly tilt their guess about where a person will look for a hidden object in the direction of where they themselves know the object to be. 9

Adults are particularly accursed when they try to estimate other people’s knowledge and skills. If a student happens to know the meaning of an uncommon word like apogee or elucidate, or the answer to a factual question like where Napoleon was born or what the brightest star in the sky is, she assumes that other students know it, too. 10When experimental volunteers are given a list of anagrams to unscramble, some of which are easier than others because the answers were shown to them beforehand, they rate the ones that are easier for them (because they’d seen the answers) to be magically easier for everyone . 11And when experienced cell phone users were asked how long it would take novices to learn to use the phone, they guessed thirteen minutes; in fact, it took thirty-two. 12Users with less expertise were more accurate in predicting the learning curves, though their guess, too, fell short: they predicted twenty minutes. The better you know something, the less you remember about how hard it was to learn.

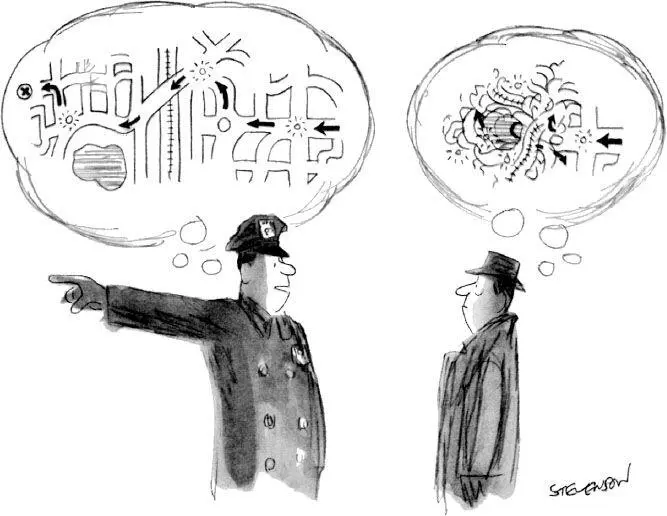

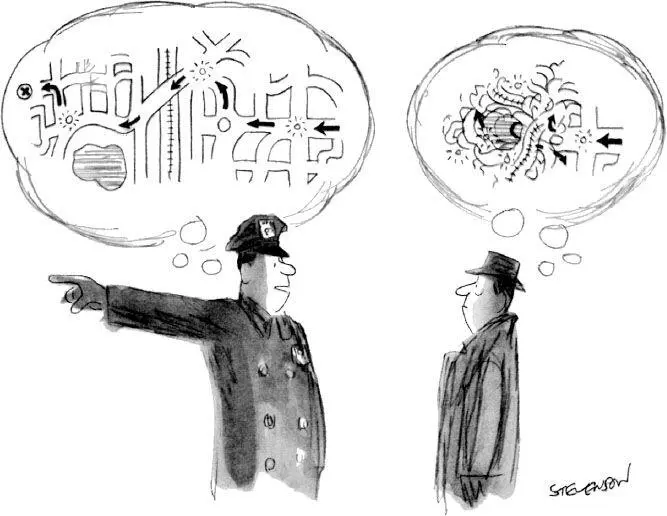

The curse of knowledge is the single best explanation I know of why good people write bad prose. 13It simply doesn’t occur to the writer that her readers don’t know what she knows—that they haven’t mastered the patois of her guild, can’t divine the missing steps that seem too obvious to mention, have no way to visualize a scene that to her is as clear as day.* And so she doesn’t bother to explain the jargon, or spell out the logic, or supply the necessary detail. The ubiquitous experience shown in this New Yorker cartoon is a familiar example:

Anyone who wants to lift the curse of knowledge must first appreciate what a devilish curse it is. Like a drunk who is too impaired to realize that he is too impaired to drive, we do not notice the curse because the curse prevents us from noticing it. This blindness impairs us in every act of communication. Students in a team-taught course save their papers under the name of the professor who assigned it, so I get a dozen email attachments named “pinker.doc.” The professors rename the papers, so Lisa Smith gets back a dozen attachments named “smith.doc.” I go to a Web site for a trusted-traveler program and have to decide whether to click on GOES, Nexus, GlobalEntry, Sentri, Flux, or FAST—bureaucratic terms that mean nothing to me. A trail map informs me that a hike to a waterfall takes two hours, without specifying whether that means each way or for a round trip, and it fails to show several unmarked forks along the trail. My apartment is cluttered with gadgets that I can never remember how to use because of inscrutable buttons which may have to be held down for one, two, or four seconds, sometimes two at a time, and which often do different things depending on invisible “modes” toggled by still other buttons. When I’m lucky enough to find the manual, it enlightens me with explanations like “In the state of {alarm and chime setting}. Press the [SET] key and the {alarm ‘hour’ setting}→{alarm ‘minute’ setting}→{time ‘hour’ setting}→{time ‘minute’ setting}→{‘year’ setting}→{‘month’ setting}→{‘day’ setting} will be completed in turn. And press the [MODE] key to adjust the set items.” I’m sure it was perfectly clear to the engineers who designed it.

Читать дальше