He swam along the edge, searching, pushing away every time a swell threatened to drag him under. His nose bled profusely, spattering the clear face of the hood with every breath. Overwhelmed with cold and fatigue, he found himself wondering what would come first, complete exhaustion or the inability to see what he was doing. A bergy bit the size of his father’s car nudged him from behind, at first startling him, then giving him an idea.

The first one had held him for a time, before tipping him off. If he could clamber up on this one, he might be able to use it as a stepping stone …

“We did not talk about this,” Wan muttered inside his bubble hood as he worked. “Drowning. Yes. Kidneys torn out by bears. Yes. But there was no mention of the insurmountable wall …”

Using all his reserves, he finally dragged and kicked himself out of the water to collapse on the ice shelf. He rolled onto his side and unzipped the hood with trembling fingers. The sudden slap of cold air took what was left of his breath away. A white moonscape of ice dazzled by the sun stretched forever around him in all directions.

The thought of it made him laugh out loud. He’d struggled so hard, only to drag himself to a different place to die.

Commander Wan’s suit had begun to freeze to the ice by the time he remembered he had something else to do.

The satellite phone. Yes. That was it. Call in the report … and then, whatever happened happened …

He fumbled with the bag containing the phone, teeth chattering, shivering badly, his hands like unworkable claws. The simple squeeze buckles seemed impossible, and he had to put his hands under his armpits for several minutes just to warm them. He finally opened the bag—only to dump a steady stream of seawater onto the ice. He could not see any rip, but it had flooded nonetheless. The phone was useless. A plastic brick.

The bag with the shotgun was still around his neck. He could use that if he needed to. If freezing to death wasn’t as painless as they said. Or if a bear came for him. He looked at the plastic buckles, then at his blue unworkable fingers and shook his head. The neoprene bag might as well have been a bank vault. However he died, the shotgun would not be a part of it.

Wan rolled onto his back. An unbearable sadness washed over him as he stared up at the incredible blue. The men on the stricken 880 , his men, five hundred feet below, would all perish without another look at the sky.

Two hours after Wan Xiuying collapsed, a strange rumble carried across the ice. He felt it before he heard it. The shivering had passed now and he was warm. In fact, the suit worked much too well, and he thought of taking it off to cool himself. He’d watched movies in his mind as he drifted in and out. Crimson Tide, Run Silent, Run Deep— the book was better. He’d found a copy in Mandarin, but he learned more from the one in English. U-571 … What was the Russian movie? China needed something … Wolf Warrior should make a good submarine movie …

The rumbling grew louder, shaking the ice under his head. A surge of adrenaline coursed through Wan’s body. A bear! Head lolling. He pushed himself onto his side with great effort.

“Come here!” he shouted. “Come and get me, you—”

But when he lifted his head, it was no bear he saw, but a large red ship in the distance, eating its way through the ice—and an orange bird hovering directly above him.

36

Captain Jay Rapoza, commanding officer of the USCGC icebreaker Healy , met the medical officer outside sick bay. Rapoza was a big man, burly, fit, barrel-chested, with a slight squint in his left eye that made him look as though he should be clenching a pipe in his teeth. He was a sailor’s sailor, fibbing just a little to his wife when he told her how heartbroken he was every time he went to sea.

“How’s he doing?” Rapoza asked.

Fortunately for the guy they’d scooped off the ice, the Healy was the only cutter in the Coast Guard to have a licensed physician’s assistant and an HS—health services technician (called a corpsman in the Navy). Lieutenant Shirley Anderson peeled off a set of blue nitrile gloves and shook her head.

“Pupils are still dilated and his heartbeat is irregular. Core temperature is eighty-seven—about a degree from gonersville in most people. We’re warming him up slowly. Have to be careful the cold blood from his extremities doesn’t rush back to his core and give him a heart attack.”

“Hope that guy plays the lottery,” Rapoza said, “because he is one lucky young man.”

“Roger that, sir,” Lieutenant Anderson said. “If I may ask, sir. No sign of a boat or snow machine?”

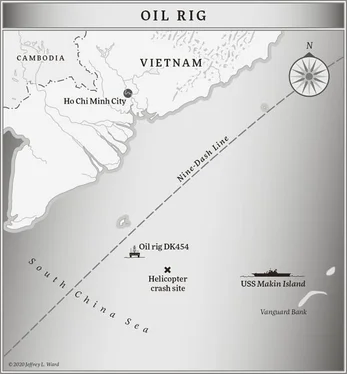

“None,” Rapoza said. “The 65 made two more passes after they dropped him off. Just a big hole in the ice. The SEIE suit suggests he escaped a submarine.”

Anderson shivered.

“I don’t like thinking about subs underneath us, sir. Creeps me out. But it does make sense. This guy is extremely talkative—mostly about submarine movies.”

“Odd,” Rapoza said. “Sonar shows the seabed at over a thousand meters. There are some underwater mountains, maybe …” He glanced at the door, then at the lieutenant. “What exactly is he saying?”

“He was talking about Lipizzaner stallions when I left.”

Rapoza saw a junior officer from engineering at the end of the passageway and called him by name. “Find Chief Cho and have him come see me.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” the ensign said. “Right away. I just passed him.”

Rex Cho came through the hatch a half minute later, cover in hand.

“Captain,” he said, presenting himself.

The whole ship knew they were heading toward an unknown radio signal, possibly a Chinese submarine. And, of course, they knew about the lone Asian man in the exposure suit they’d picked up off the ice, but they’d not all been told the details.

“I’m sorry, Captain,” Cho said. “I haven’t spoken Chinese since grade school, since my nainai passed away.”

“Understood,” Rapoza said. “But I’d like you in the interview with me, just in case you pick something up. He’s kind of out of his head. He might see you as a friendly face and be a little more forthcoming.”

“Aye, sir,” Cho said.

It took all of ten seconds for the man to tell Chief Petty Officer Cho that he was “Commander Wan Xiuying, executive officer of 880 .” He drifted off twice, rambling about enigma machines and Nazi U-boats when he awoke. Some of it was in English, and Rapoza recognized them as lines from Hollywood movies. He first answered Chief Petty Officer Cho in Chinese, but when Cho repeated the question in English, Commander Wan threw his head against the pillow and rolled his eyes as if to say, Oh, you want to play that game? Okay … and then answering in English. Most of it seemed like nonsense, but many recent events over the past few days fell squarely in the unbelievable column.

Coded signals, strange noises from the bottom of the Chukchi, and now a Chinese submariner coughed up on the ice like some Jonah—Captain Rapoza grabbed a piece of paper from Lieutenant Anderson’s desk and took notes.

Though the Chinese submariner seemed fluent in English, his physical and mental state slurred his rambling words, rendering them difficult to understand. There had been a fire on a submarine … a professor Liu was dead or near death. Rapoza got that much.

Commander Wan lifted his head, tugging against his IV line, attempting to get out of the bed.

“Must call,” he said. “Crew … destroy …”

Anderson and Cho each took a shoulder and guided him gently back to the pillow.

“Burned,” he said, thrashing his head back and forth. “Save crew! Hai shi shen lou … no good. Destroyed … Fire. Hai shi shen lou … Gone! Hai shi shen lou …”

Читать дальше

![Александр Ирвин - Tom Clancy’s The Division 2. Фальшивый рассвет [litres]](/books/417744/aleksandr-irvin-tom-clancy-s-the-division-2-falsh-thumb.webp)