He felt that way about the sea.

The pilots kept the cabin on the chilly side, so most passengers wore their coats or at least a heavy wool sweater during the flight. Most of the Uyghur men wore black fur hats pulled low over their eyes, like the winter hat worn by Brezhnev in all the newsreels. Others wore ball caps, or snap-brims. A couple of the older ones wore large fur Kyrgyz hats, similar to a Russian ushanka but wider at the earflaps, perfectly suited to their long white beards and Turkic features. Dark eyes and aquiline noses peered back and forth at the gathering twilight out of the windows on each side of the plane.

Clark watched the ground rise up to meet him out the window to his left. A dusty haze hung over the dull gray of the city and muted brown of the surrounding countryside. Patches of grimy snow clung to the shadows. The canal along the highway leading from the airport northeast of the town flowed full of chocolate-brown water. A convoy of three white-topped military troop carriers rolled down the highway east of the city. Pickups and larger trucks shared the roads with taxis and scooters.

Clark could already feel the grit of dust in his teeth and the chill on his neck just from looking out the window. It was no wonder everyone on the plane wore winter hats.

The plane bounced once, crabbing into a stiff crosswind before straightening up and settling onto Kashgar Airport’s only runway.

The police minders followed Clark off the plane and then jumped ahead when he was held up at Immigration and Customs. He was sure he’d see them again. No doubt about that.

The uniformed Han officer grunted as Clark slid his Canadian passport and visa, courtesy of Adam Yao’s friend in Beijing, across the counter. The officer perused it with the jaundiced eye of someone accustomed to being lied to on an hourly basis.

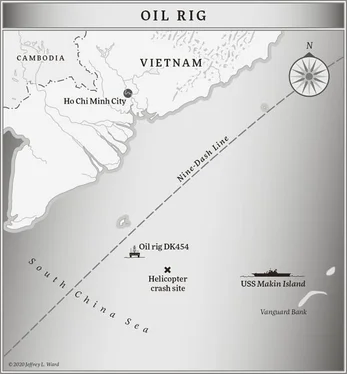

He asked Clark a couple perfunctory questions about the purpose of his trip. For his part, Clark tried very hard to hide the predatory edge in his eyes by acting bewildered. The three-thousand-mile trip from Ho Chi Minh City via Guangzhou and Urumqi had sapped him, and he was able to play weary traveler without acting. The officer barked something unintelligible, making the bewildered look easy to sustain.

It sounded as if he’d asked Clark if he had a jeep.

Clark shrugged and tapped his ear. It was better for the officer to think he was simply dealing with an old deaf guy rather than to be offended because Clark couldn’t understand his English.

“You have the GPS?” the officer pantomimed, using his index finger like a compass needle. “For navigation.”

“On my phone,” Clark said, honestly.

“Mobile phone!” The man snapped his fingers. “Give to me.”

Clark fished the phone out of his jacket pocket and passed it to the officer without argument.

“Extra battery?”

Clark dug out the spare charging block as well.

“Passcode!

“I …”

“Passcode or I do not give back,” the man said. He gazed up at Clark without lifting his head.

Clark gave him the code to unlock the screen.

The officer scrolled, perusing the various icons, then said, “Do not use in China.”

“The phone?”

The officer gave a disgusted shake of his head, then pointed to the map icon on the screen, raising his voice for the deaf Canadian at his station.

“No JEEPS in China.”

“I understand,” Clark said. “No GPS.”

The officer slid the phone and passport back, but kept the extra battery for himself, giving no explanation. It was a small sacrifice to the Immigration and Customs gods.

One problem down, Clark moved to the next. He traveled with just a carry-on, so he made his way directly through the terminal, past the crowd of passengers. They squatted on tiny plastic stools by their bags, eating instant noodles or shanks of meat, while they waited for flights that rarely departed on schedule.

The two police minders, Horse Face and Doughboy, resumed their tail before Clark made it out the glass doors. Blowing yellow dust muted the glow of the streetlamps, forcing Clark and everyone else to bow their heads against the biting wind. The two minders trotted to keep up as he skirted a group of construction workers in hard hats laying rebar for a new sidewalk between the buses and taxi stand.

He’d let them follow him for now. But sooner or later, he’d have to lose them or lie to them.

Clark was, in fact, extremely good at lying. Sociopathy within proper bounds, the shrinks at Langley called it. Clark had never considered himself a spy in the strictest sense of the term. He was an operator, had been since he was a pup. Operators lied to get where they needed to be—or, more often than not, to get out of the grease after the job was complete. He grabbed intel when he came across it, of course, but in the main, he used other people’s intel to go in, do his thing, and then slip away.

A good percentage of the time his thing had to do with getting some spy out—or killing one.

Hala Tohti helped load boxes of oiled noodles onto the back of her aunt’s scooter. Her aunt’s normally olive skin was chalky pale. She’d been up at all hours of the night, sewing, cooking, reading, anything but sleeping.

“I can take these to the market,” Hala said, nodding at the noodles.

“I will be fine,” Zulfira said.

A cold wind howled up the dusty street, picking up bits of trash and causing them to dance under the light posts, bristling with security cameras. Zulfira pulled her woolen scarf around her neck and shivered.

“I think you may be ill,” Hala said.

“I said I will be fine.”

The busy Jiefang Night Market was only a few blocks away, but Zulfira swayed in the wind as if she might fall over before making the short trip.

Zulfira climbed aboard the scooter with unsteady legs. “I will drop off the noodles to Rami and return at once,” she said, head bent against the wind. “Chop the meat while I am gone. We must have dinner ready when Mr. Suo arrives.”

Hala’s throat convulsed, making her warble like a frightened child—which made her angry with herself. “What if he comes while you are gone?”

“Ren sent word. Mr. Suo is delayed with meetings. He will be here in two hours. Plenty of time.”

Hala knew better than to argue. She was a guest in her aunt’s home.

Hala watched her aunt’s scooter disappear into the dusk before going back into the house. She was no stranger to work—and there was always plenty of it to do. Her mother had taught her to make savory rice plov, and chop mince and vegetables to fill dough for samsa, by the time she was six. She could joint a chicken with her eyes closed, especially with her uncle’s razor-sharp cleaver.

She stood on a stool while she worked, chicken carcass on a flat board, cleaver in her right hand. Holding a drumstick—yellow foot and claws attached—away from the breast at an angle, she pressed the cleaver against the joint and popped it away, setting aside the neatly separated leg. What else could she do? She saw the way the fat bureaucrat Suo and his secretary, Ren, looked at both her and her aunt. Oh, Fat Suo liked Zulfira, but Hala was old enough to realize men looked at her as well with glazed eyes and sagging jaws. Fat Suo would be back soon, looking at her like she was a sweet. But Zulfira was strong. Zulfira would protect her.

Hala had seen it before, at the dance and gymnastics academy in Nanjing. Coaches sometimes looked at the older girls that way. They took them on walks or to their offices upstairs. None of the girls ever said what happened when they came back to the dormitory, but they cried a lot. Some of them got so sick that they had to leave the school.

Sometimes, early on when she was still only seven years old and she’d just been identified as a gymnastics prodigy and sent away to train for the glory of the Motherland, Hala wished she would get sick so she could go home like the other girls. Later, when she was old enough to understand some of it, she learned the girls hadn’t gone home. They’d left the school in shame, to have babies. Hala had grown up around farm animals and understood the basics, but not the narrow-eyed looks some of the coaches had when they looked at the older girls.

Читать дальше

![Александр Ирвин - Tom Clancy’s The Division 2. Фальшивый рассвет [litres]](/books/417744/aleksandr-irvin-tom-clancy-s-the-division-2-falsh-thumb.webp)