And fire.

Chavez broke the surface in a spot between the patches of burning oil and debris. He fought the pressing urge to breathe until he was reasonably sure he wasn’t about to sear his lungs.

The flames looked worse from below than they did up top, with small patches of fuel and rafts of burning plastic bobbing between the waves. Midas had been right beside him, so Chavez scanned for him first, and found him immediately. He was helping Adara get a wounded Dom Caruso into a yellow rubber lifeboat with the aid of two Vietnamese roustabouts, one of whom looked badly burned himself. A strong swimmer, Chavez used adrenaline to help him battle the chop, and he reached the raft in seconds.

Caruso’s left leg was bent unnaturally at the knee. His eyes gleamed with pain, but he was conscious. Looking outbound while Midas and Adara got him into the boat, he was the first to see Chavez in the water. “I’m good,” he sputtered, wincing as he slithered over the side of the tube.

Midas patted Adara’s shoulder, then turned, almost colliding with Ding.

“Holy shit, you’re a sight for sore eyes.” Midas sputtered, wiping water away from his beard. “I was just coming back to find you.”

“I’m good to go,” Ding said, bobbing and clinging to a line on the side of the raft. “You and Adara?”

“Banged up but otherwise intact.”

Midas slipped over the side, and without another word, both men swam among the debris and began to drag survivors toward the bobbing rafts. They found their pilot first, alive, but one arm broken, the other burned, clinging to a piece of insulation foam. Injured on impact, the man’s first inclination had been to see to his passengers. Chavez and Midas returned the favor and got him back to the raft with Adara and Dom.

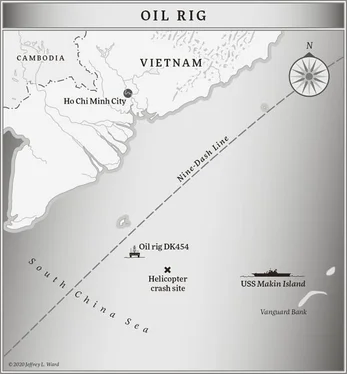

Twelve minutes post-explosion, there were nine survivors in Adara’s raft, and fifteen in a second that Chavez and Midas had lashed alongside the first. A third raft bobbed in the chop some two hundred meters away, and looked to contain at least a dozen men. The chopper pilot spoke Vietnamese well enough to learn that there had been fifty-six crewmen on the rig, which left over twenty still unaccounted for.

Chavez hauled himself into the raft, hoping the extra couple of feet in elevation above the chop would give him a better view. The water was warm, but exertion and the massive adrenaline dump of the explosion and crash left him and the others shaking violently, chilled to the core.

One of the Vietnamese drillers—with much younger eyes than Chavez’s—was first to see the choppers on the horizon.

“Probably Chinese,” the pilot said through chattering teeth.

Midas wallowed into a kneeling position on the rubber raft’s trampoline floor and shielded his eyes to get a better look.

“Nope,” he said. “Those are U.S. Navy birds.”

The Seahawks arrived first, circling to approach from the west, then hovering close to the surface of the ocean as they dropped two rescue swimmers. Backlit by a low sun, the clouds of mist driven up by the churning rotors threw dazzling rainbows of color into the air below each gunmetal-gray bird.

Adara gave Chavez a good-natured punch in the shoulder with a shaky hand. “Bet you Army boys are happy to see the Navy now …”

The Navy swimmer broke the surface a few feet from the raft. He wore a black neoprene shorty and red helmet outfitted with a flashing strobe so the pilots could keep an eye on him. A black dive mask covered his youthful face.

“Petty Officer Third Class Aaron Ward,” the swimmer said, as if he’d just sidled up to the bar instead of hanging on to the side of a raft with hurricane-force prop wash battering the ocean a few dozen yards away. “United States Navy. How you folks holding up?”

Petty Officer Ward’s demeanor was relaxed—because calm was contagious—but he worked fast to triage the injured in the raft while the choppers scoured the surface for other survivors.

The helicopter pilot had it the worst, and Petty Officer Ward saw to him first, radioing his chopper with a situation report that would be passed on to his ship. It wasn’t long before everyone on the rafts was wrapped in foil space blankets like so many shivering baked potatoes.

Inflatable runabouts deployed from Makin Island ’s well-deck as she drew nearer, allowing the monstrous ship to stand off, protecting it from possible danger, and those in the water from its massive bulk. The runabouts made for an easier rescue than the helicopter hoist, letting the rescue swimmers get back in their respective birds and continue the search for survivors.

Chavez was last off the raft. He stayed out of the way as the coxswain ran the inflatable up the ramp of the Makin Island ’s well-deck. Sailors and Marines were on hand to assist survivors as they climbed onto the ship. Ears half clogged with water and still shivering, Chavez was vaguely aware of a murmur among a small group of Marines.

One of them stepped away from the others.

Pausing mid-step as he climbed out, Chavez looked to his left. What he saw nearly sent him tumbling back into the runabout.

A slender lance corporal with green eyes administered an on-the-spot correction to a Marine PFC who he must have thought was being too rough bringing the Vietnamese roustabouts aboard. The correction was direct, colorful in its language, and over quickly.

Chavez, still dizzy and near hypothermia, squinted, turning his head slightly to be certain he wasn’t seeing things. Satisfied, he chuckled to himself, suddenly much warmer than he had been.

“You kiss your mama with that mouth, Marine?”

The green-eyed lance corporal braced, wheeling to look directly at Chavez. His jaw dropped and his eyes flew wide.

“Dad?”

10

John Clark was almost finished with a call from Mary Pat Foley when his phone buzzed. He’d been expecting to hear from Ding, but this was an unknown number, so he let it go to voicemail. The same number called back twice more in rapid succession, prompting him to put the director of national intelligence on hold—something he was certain few people ever got to do.

It was Ding, calling on a borrowed phone.

Clark’s helicopter touched down on the USS Makin Island an hour and a half later. By then, rescue operations had turned into body recovery and Lance Corporal Chavez had received permission to break away from his platoon. Captain Jackson cleared the wardroom so the boy could meet privately with his father and grandfather.

Clark had time to brief Chavez of the basics of Foley’s call, but little else. The urgency of the situation in China drove him to want to return to the hotel immediately and formulate a plan, but the idea of spending a minute or two with his grandson made him step back and take a breath. Jack and Lisanne were already working logistics for a quick move and they were all waiting on direction from Adam Yao, anyway. He could spare a couple minutes.

Captain Jackson made certain everyone was comfortable in the wardroom and then, grinning, said, “Looks like the Marine has a question or two.”

“That I do, sir,” JP said. His nose was crooked now. Telltale scars above his right eyebrow and his lower lip had taken the brunt of what looked to have been a serious fight. Shoulder blades pinned, he stood so straight Clark thought his back might snap. Clark suppressed a smile, remembering the hundreds of times as a grandfather that he’d told the boy to stand up straight. As much of a Navy man as he was, he had to admit there wasn’t any straight back like a Marine straight back.

Captain Jackson gave JP a soft nod. “Stand at ease, son. In fact, have a seat. Not sure how much your dad is going to tell you, but it’d probably be best if you were sitting down for whatever it is.”

Читать дальше

![Александр Ирвин - Tom Clancy’s The Division 2. Фальшивый рассвет [litres]](/books/417744/aleksandr-irvin-tom-clancy-s-the-division-2-falsh-thumb.webp)