Michael Cox - The Meaning of Night

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Cox - The Meaning of Night» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Meaning of Night

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Meaning of Night: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Meaning of Night»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Meaning of Night — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Meaning of Night», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To this end, a few weeks earlier, I had written to Mr Talbot, and he had kindly agreed to receive me at his house at Lacock, *where I was inducted into the wonderful art of producing photogenic drawings of the kind I had seen in New College, and into all the mysteries of sciagraphs, †developers, and exposure. I was even given one of Mr Talbot’s own cameras, dozens of which had lain all about the house and grounds. They were perfect little miracles: simply small wooden boxes – some of them no more than two or three inches square (Mrs Talbot called them ‘mousetraps’) – made to Mr Talbot’s design by a local carpenter, with a brass lens affixed to the front; and yet what wonders they produced! I had returned home to Sandchurch, afire with enthusiasm for my new hobby, and eager to begin taking my own photographs as soon as possible.

Then came the hot July day when I closed behind me the front door of the house on the cliff-top for what I thought would be the last time. I paused for a moment, beneath the chestnut-tree by the gate, to look back at the place that I had formerly called home. The memories could not be restrained. I saw myself playing in the front garden, eagerly climbing the tree above me to look out from my crow’s-nest across the ever-changing waters of the Channel, and trudging up and down the path, in every season and all weathers, to and from Tom’s school. I recalled how I would stand watching my mother through the parlour window, doubled over her work for hour after hour, never looking up. And I remembered the sound of wind off the sea, the cry of sea birds as I woke every morning, the ever-present descant of waves breaking on the shore below the cliff, thundering in rough weather like the sound of distant cannon. But they were Edward Glyver’s memories, not mine. I had merely borrowed them, and now he could have them back. It was time for my new self to begin making memories of its own.

During my first few weeks in Camberwell, I made several trips to town in search of employment. All proved fruitless, and, soon, with my little store of money diminishing fast, I began to fear that I should have to fall back on tutoring again – a most uncongenial prospect. Perhaps if I had possessed a degree, my way might have been made easier; but I did not. Phoebus Daunt had put paid to that.

The summer began to pass, and, determined I would not subside into idleness, I turned again to my mother’s journals. It was then that I made a great discovery.

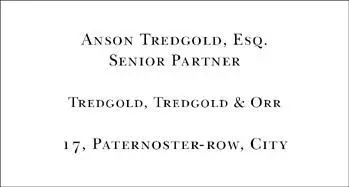

My eye had happened to fall on an entry dated ‘31.vii.19’: ‘To Mr AT yesterday: L not present, but he kindly put me at my ease & explained what was required.’ ‘L’ was, of course, Laura Tansor; but the identity of ‘Mr AT’ was unknown to me. On an impulse, I searched out a tied bundle of miscellaneous documents, all of which dated from 1819. It did not take long to extract a receipt for a night’s stay, on the 30th of July of that year, at Fendalls Hotel, Palace Yard. Adhering to the back was a card:

‘Mr AT’, I thought, could now be identified, tentatively, as Mr Anson Tredgold, solicitor. This now explained an earlier entry: ‘L has agreed to my request & will speak to her legal man. She understands that I fear discovery & require an instrument that will absolve me of blame, if such a thing can be contrived.’ It seemed clear from this that some form of legal document or agreement had been drawn up, to which both women had been signatories. Of such an agreement I had found no trace amongst my mother’s papers; but, seeing its likely importance to my case, I began there and then to devise a way of getting my hands on a copy of it. My great enterprise had begun.

The next day I wrote to the firm of Tredgolds, in a disguised hand, and using the name Edward Glapthorn. I described myself as secretary and amanuensis to Mr Edward Charles Glyver, son of the late Mrs Simona Glyver, of Sandchurch, Dorset, and requested the pleasure of an interview with Mr Anson Tredgold, on a confidential matter concerning the aforementioned lady. I waited anxiously for a reply, but none came. The tedious weeks dragged by, during which I continued to make a number of enquiries concerning employment, without success. August came and went, and I began to despair of ever receiving a reply to my enquiry to Mr Anson Tredgold. It was not until the first week of September that a short note arrived, informing me that a Mr Christopher Tredgold would be pleased to receive me privately (the word was underlined) on the following Sunday.

The distinguished firm of Tredgold, Tredgold & Orr has already been mentioned in this narrative, in connexion with my neighbour Fordyce Jukes, and as the legal advisers of Lord Tansor. Their offices were in Paternoster-row, *in the shadow of St Paul’s: a little island of the legal world set in a sea of publishers and booksellers, whose activities have made the street proverbial amongst those of a literary inclination. The firm occupied a handsome detached house, on the other side of the street from the Chapter coffee-house; as I was soon to discover, part of the building, unlike many in the City, was still used by the present Senior Partner, Mr Christopher Tredgold, as his private residence. The ground floor formed the clerks’ offices, above which, on the first floor, were the chambers of the Senior Partner and his junior colleagues; above these, occupying the second and third floors, were Mr Tredgold’s private rooms. One peculiarity of the building’s arrangement was that the residential floors could also be reached from the street via two side staircases, each with its own entrance that gave onto two narrow alleys running down either side of the house.

It was a fine morning, bright and dry, though with a distinct feeling of impending autumn in the air, when I first saw the premises of Tredgold, Tredgold & Orr, which were soon to become so familiar to me. The street was unusually quiet, but for the dying chimes of a nearby church clock and the rustle of a few newly fallen leaves drifting along the pavement and gathering beside me in a little twirling heap.

A manservant showed me up to the second floor, where Mr Christopher Tredgold received me in his drawing-room, a well-proportioned apartment whose two tall windows, looking down on the street, were swathed and swagged in plush curtains of the most exquisite pale yellow, to which the sunlight streaming in from outside added its own soft lustre.

All, indeed, was shine and softness. The carpet, in a delicate pattern of pink and pale blue, had a deep springy pile, reminding me of the turf against which I had lain in my little nook above the Philosophenweg. The furniture – sparse but of the finest quality, and much against the present ponderous taste – gleamed; light danced off brilliantly polished silver, brass fittings, and shimmering glass. The long sofa and tête-à-tête chair, *in matching blue-and-gold upholstery, that were set around the elegant Adam fireplace – each item also enclosing an abundance of perfectly plumped cushions of Berlin-work – were deep and inviting. In the space between the two windows, beneath a fine Classical medallion, stood a violincello on an ornate wrought-brass stand, whilst on a little Chippendale table beside it was laid open the score of one of the divine Bach’s works for that peerless instrument.

Mr Christopher Tredgold I judged to be a gentleman of some fifty years or so. He was of middling height, clean shaven, with a full head of feathery grey hair, a fine square jaw, and eyes of the most piercing blue, set widely in his broad, tanned face. He was dressed immaculately in dove-grey trousers and shining pumps, and held in his left hand an eye-glass on a dark-blue silk ribbon attached to his waistcoat, the lens of which, during the course of our interview, he would polish incessantly with a red silk handkerchief kept constantly by him for this purpose. In all the time of our subsequent acquaintance, however, I never once saw him raise the glass to his eye.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Meaning of Night»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Meaning of Night» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Meaning of Night» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.