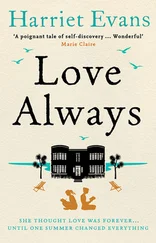

Harriet Evans - Love Always

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Harriet Evans - Love Always» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love Always

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love Always: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love Always»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love Always — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love Always», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Miranda & I are going for our walk now. She’s right, we should just get away from here, as soon as we can. But I’m so tired. I feel old, all of a sudden. Old and tired of all this. I will report back, darling diary. I know I can trust you. You will be here in the dark in the bedside table, waiting for me. I’ll be back soon.

Love Always,

Cecily

PART FOUR

March 2009

Chapter Thirty-Eight

It is cold and dark in the room, and as I look up, my neck, shoulders and legs ache from the tense position I’ve been in over the last hour. The only point of light is the lamp next to me. It shines on the yel owing pages of the diary. Everything else around it is black. It is almost a surprise to me, when I put my hands up to my cheeks, to find that tears are running down them.

The shadow of my hands makes the light flicker on the brick wal s, and I jump. It is very quiet, but the room seems to be crowded, with voices, people . . . I shiver and stand up. I wish I wasn’t here. I wish I was somewhere with someone I know. Someone who loves me, someone who I could turn to and say, my God, this is horrible.

I can’t. I’m al alone, and her voice is echoing in my head. I want to see her. More than anything, suddenly. I didn’t know her before, so I couldn’t miss her, and this is what’s making me cry. I love this bold, intel igent, charming, eccentric, eager young girl, whose scrawling pages in front of me are so slapdash and immediate it’s as if she’s just run out of the room. I can see why Guy fel in love with her. I wish I had known her. I wish I could know what she might have done next, had she lived. There is something so hopeless about her last day alive; a girl worn out by the adults around her, by the life she had to live, and not even sixteen.

When she died, she left them al behind, and I realise, now, that they have been preserved like that, al of them – Mum, Archie, Louisa, Granny, Arvind – kept in a drawer along with the diary, not al owed to live the lives they wanted. Even Guy, who married someone else and got away from them, is a curiously reduced version today of the person he was in the diary. Poor, poor Guy. At the thought of him, my heart clenches and my eyes sting with fresh tears. Now I understand, now I know why he insisted I cal him after I’d finished it. How must it have been for him, reading that diary after al these years, having tried to forget her, never having known why she died? To find out about his brother like that, to . . . oh, it’s so sad. The whole thing is just so sad. I think of Mum. I wonder where she is. Oh, Mum. I’m sorry.

Memories start rushing back to me as I stand up slowly, my legs aching from sitting stil in the cold, dark room. Of me on Granny’s knee, teaching me to play the piano. Letting me sip her Campari and soda while she put on her earrings, dabbed scent onto her slender wrists. And her beautiful face viewed through the carriage window, waving enthusiastical y at me as each summer train pul ed into Penzance station and I thought – I thought

– I was home, with my real mother, not living this sham life with a mother who forgot where my school was and didn’t like birthday parties.

My granny, my favourite person in the world: was this real y her, this woman who tries on her daughter’s clothes, who sleeps with young men, who has to have attention and approval and glamour and beauty and simply takes it if she doesn’t have it?

I look down at the diary. Yes, yes, it was.

And that furious, awkward, eccentric and beautiful teenager, who has lived in the shadow of this ever since, suspected, mistrusted, abandoned by the people who should have most been looking out for her, was that real y my mother?

Yes, I guess it was.

The ring, Cecily’s ring, is stil around my neck. She put it on the day she died. Granny wore it every day since, and suddenly it feels as though it’s choking me, and my heart feels as though it’s being squeezed. I rip it off my neck, almost panting. I switch the kettle on and stare at nothing. My breathing gets more rapid as I think it al through, and there are so many things that make sense. Like why Mum hates going down to Summercove, why she and Granny didn’t get on, why Mum and Archie are so close, and why kind, caring Louisa is baffled by her cousins and their behaviour, always has been.

And then there are things I just don’t understand. Like how Granny could sit in a room with the Bowler Hat, knowing what they did. Like how Mum could stand it. And Arvind – does he know? Does Archie? Does Louisa real y not know what her husband has done?

I think about the Bowler Hat, the way he’s present and yet not real y present at everything, this cipher. This empty, attractive casing of a man.

Forty-six years ago, he was the same, just a younger, priapic version of that. I wonder if he connects the two, if he knows what he’s done?

The kettle sounds louder and louder, the whistling steam rising up and moistening my face. I stare into the white-grey plumes.

How could Granny live there year after year, knowing she was as good as responsible for her daughter’s death? Cecily herself said the steps were slippery, and they’d mentioned it a couple of times, so why didn’t she or Arvind get them fixed? How could she let people think her own daughter might have been responsible for her sister’s death? How could she . . .

And I can’t think about it any more.

I go into the bedroom. The camomile tea tastes like cardboard. The flat is silent. I climb into bed. I pick up Cecily’s diary again and flick through it – it seems the only real, concrete thing in my life. Words, phrases, jump out at me.

Mummy doesn’t like Miranda being beautiful.

Dad has lived most of his life in another country. It’s a part of me, and I don’t know it.

We’re not the family I thought we were.

I real y can’t write what I saw.

I think it’s too late, for him and for me.

I think it’s too late, for him and for me . . .

I can’t read the last couple of pages again. They’re too painful. I stare at the diary, and the words swim in front of my eyes, and soon I slide into sleep, propped up by pil ows.

Chapter Thirty-Nine

That is Friday. On Monday morning, I wake up and I know I can’t stay in the flat by myself any more. It’s not just the loneliness: I’ve been lonely for a while, I realise. It’s that every time I look around there’s something else to remind me of something I don’t want to be reminded of. It just holds bad memories for me, as if sitting there in the darkness as I read Cecily’s diary somehow released them al . I can’t do it any more. Perhaps I was holding on to some tiny hope that Oli and I might get back together again, but I know now that’s never going to happen; this has clarified everything.

We need to sort the flat out, and we need to crack on with the divorce. First things first, I need to get out of here. I ring up Jay, and ask to stay with him.

The great thing about Jay is he doesn’t ask questions, and he doesn’t fuss. He is waiting there when I turn up at his flat in Dalston an hour later, with a hastily packed suitcase. He gives me a cup of coffee and makes me some toast.

‘I just don’t want to be there any more,’ I say. I wipe a tear away from my cheek.

‘Why now?’ he says. ‘I mean, you’ve been on your own there for a while.’

I don’t want to tel him about the diary. If I tel him, he’l want to read it, and he’l find out about our grandmother. Now I can see what Mum has been doing al these years, in her own way: protecting Granny’s reputation, for the sake of others. We are sitting in his light, roomy, first-floor Georgian flat, just off De Beauvoir Square, and as I look out of the window I notice the trees have buds on them. There are no trees on my street.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love Always»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love Always» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love Always» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.