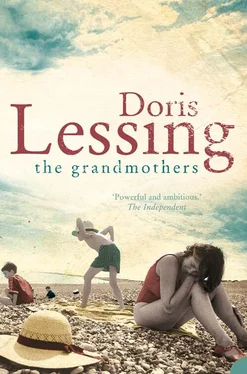

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘There you are,’ said Lil to Roz. ‘It’s a beginning. He’s getting tired of me.’

But Ian showed no signs of relinquishing Roz. on the contrary. He was attentive, demanding, possessive, and when one day he saw her lying on her pillows, lovemaking just concluded, smoothing down loose ageing skin over her forearms, he let out a cry, clasped her, and shouted, ‘No, don’t, don’t, don’t even think of it. I won’t let you grow old.’

‘Well,’ said Roz, ‘it is going to happen, for all that.’

‘No.’ And he wept, just as he had done when he was still the frightened abandoned boy in her arms. ‘No, Roz, please, I love you.’

‘So I mustn’t get old, is that it, Ian? I’m not allowed to? Mad, the boy is mad,’ said Roz, addressing invisible listeners, as we do when sanity does not seem to have ears.

And alone, she felt uneasiness, and, indeed, awe. It was mad, his demand on her. It really did seem that he had refused to think she might grow old. Mad! Hut perhaps lunacy is one of the great invisible wheels that keep our world turning.

Meanwhile Tom’s father had not given up his aim, to rescue Tom. He made no bones about it. ‘I’m going to rescue you from those femmes fatales he said on the telephone. ‘You get up here and let your old father take you in hand.’

‘Harold is going to rescue me from you,’ said Tom to his mother, on his way to Lil’s bed. ‘You’re a bad influence.!

‘A bit late,’ said Roz.

Tom spent a fortnight in the university town. In the evenings a short walk took him out into the hot sandy scrub where hawks wheeled and watched. He became friends with Molly, Roz’s successor, and with his half-sister, aged eight, and a new baby.

It was a boisterous child-centred house, but Tom told Ian he found it restful.

‘Nice to get to know you, at last,’ said Molly.

‘And now,’ said Harold, ‘don’t leave it so long.’

Tom didn’t. He accepted an offer to direct West Side Story in the university theatre, and said he would stay in his father’s house.

As always, the young women clustered and clung. ‘Time you were married, your father thinks,’ said Molly.

‘Oh, does he?’ said Tom. ‘I’ll marry in my own good time.’

He was in his late twenties. His classmates, his contemporaries, were married or had ‘partners’.

There was a girl he did like, perhaps because of her difference from Lil and from Roz. She was a little dark-haired, ruddy-faced girl, pretty enough, and she flirted with him in a way that made no claims on him. For here, so far from home, from his mother and from Lil, he understood how many claims and ties bound him there. He admired his mother, even if she exasperated him, and he loved Lil. He could not imagine himself in bed with anyone else. But they bound him, oh, yes, they did, and Ian, too, a brother in reality if not in fact. Down there - so he apostrophised his city, his home, so much part of the sea that here, when he heard wind in the bushes it was the waves he heard. ‘Down there, I’m not free.’

Up here, he was. He decided to accept work on another production. That meant another three months ‘up here’. By now it was accepted that he and Mary Lloyd were a unit, ‘an item’. Tom was passive, hearing this characterisation of him and Mary. He neither said yes, nor did he say no, he only laughed. Hut it was Mary who went with him to the cinema or who came home with him to his father for special meals.

‘You could do a lot worse,’ said Harold to his son.

‘But I’m not doing anything, as far as I can see,’ said Tom.

‘Is that so? I don’t think she sees it like that.’

Later Harold said to Tom, ‘Mary asked me if you’re queer?’

‘Gay?’ said Tom. ‘Not as far as I know.’

It was breakfast time, the family ate at table, the girl watching what went on, as little girls do, the infant babbling attractively in her high chair. A delightful scene. Part of Tom ached for it, for his future, for himself. His father had wanted ordinary family life and here it was.

‘Then, what gives?’ asked Harold. ‘Is there a girl back home, is that it:’

‘You could say that,’ said Tom, calmly helping himself to this and that.

‘Then you should let Mary go,’ said Harold.

‘Yes,’ said Molly, on behalf of her sex. ‘It’s not fair.’

‘I wasn’t aware I had her tied.’

‘Tom,’ said his father.

‘That’s not on’ said his father’s wife.

Tom said nothing. Then he was in bed with Mary. He had slept only with Lil, no one else. This fresh young bouncy body was delightful, he liked it all, and took quiet satisfaction in Mary’s, ‘I thought you were gay, I really did.’ Clearly, she was agreeably surprised.

So there it was. Mary came often to spend the night with Tim in Harold’s and Molly’s house, all very en famille and cosy. If weddings were not actually mentioned, that was because tact had been decided on. And because of something else, still ill-defined. In bed, Mary had exclaimed over the bite mark on ‘loin’s calf. ‘God,’ said she. ‘What was this? A dog?’ ‘That was a love bite,’ he said, after thought. ‘Who on earth …’And Mary, in play, tried to fit her mouth over the bite, but found Tom’s leg, and then Tom, pulling away from her. ‘Don’t do that,’ he said, which was fair enough. But then, in a voice she had certainly never heard from him, nor anything like it: ‘Don’t you dare ever do that again.’

She stared, and began to cry. He simply got off the bed and went off into the bathroom. He came back clothed, and did not look at her.

There was something here … something bad … some place where she must not go. Mary understood that. She felt so shocked by the incident that she nearly broke off from Tom, then and there.

Tom thought he might as well go back home. What he loved about being ‘up here’ was being free, and that delightful condition had evaporated.

This town was imprisoning him. It was not a large one, but that wasn’t the point. He liked it, as a place, spreading suburbs of bungalows around a centre of university and business, and all around the scrubby shrubby desert. He could walk from the university theatre after rehearsal and find himself in ten minutes with strong-smelling thorny bushes all around, and under his feet coarse yellow sand where the fallen thorns made pale warning gleams: careful, don’t tread on us, we can pierce through the thickest soles. At night, after a performance or a rehearsal, he walked straight out into the dark and stood listening to the crickets, and above him the unpolluted sky glittered and sparked off coloured fire. When he got back to his father’s, Mary might he waiting for him.

‘Where did you get to?’

‘I went for a walk.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me? I like to walk too.’

‘I’m a bit of a lone wolf,’ said Tom. ‘I’m the cat who walks by himself. So, if that’s not your style, I’m sorry.’

‘Hey,’ said Mary. ‘Don’t bite my head off.’

‘Well, you’d better know what you’re letting yourself in for.’

At this, Harold and Molly exchanged glances: that was a commitment, surely? And Mary, hearing a promise, said ‘I like cats. Luckily.’

But she was secretly tearful and fearful.

Tom was restless, he was moody. He was very unhappy but did not know it. He had not been unhappy in his life. He did nut recognise the pain for what it was. There are people who are never ill, are unthinkingly healthy, then they get an illness and are so affronted and ashamed and afraid that they may even die of it. Tom was the emotional equivalent of such a person.

‘What is it? What’s wrong with me?’ he groaned, waking with a heavy weight across his chest. ‘I’d like to stay right here in bed and pull the covers over my head.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.