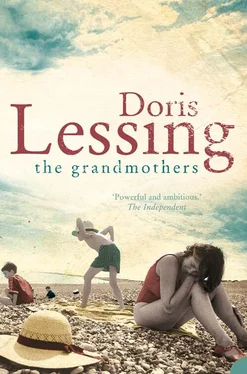

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘My auntie’s in hospital.’

‘Who else do you go to?’ - thinking of the networks of people used by hint and by Thomas.

‘My auntie’s friend.’

At last necessity stopped Victoria’s sobs. She said her aunties friend was Mrs Chadwick, yes, there was a telephone.

Edward rang several Chadwick’s until he reached a girl who said her mother was out. She was Bessie. Yes, she thought it would be all right if Victoria stayed the night. There was no bed for her here tonight: Bessie had her friends in to watch videos.

‘That’s all right, then,’ said Edward, abandoning his own plans for the evening. This necessitated several more telephone calls.

Meanwhile, Victoria was wandering about the great room, which she had not yet really understood was the kitchen, staring, but not touching, and she was wondering, Where are the beds?

There were no beds.

‘Where do you sleep, then?’ she asked Edward.

‘In my bedroom.’

‘Isn’t this your room?’

‘This is the kitchen,’

‘Where are all the other people?’

He had no idea what she meant. He sat, telephone silent in front of him, leaning his head on a fist, contemplating the child.

At last he said, hoping that this was what she was on about, ‘My mother’s room is at the top of the house, and I have a room just up the stairs, and so does Thomas.’

Some monstrous truth seemed trying to get admittance into Victoria’s already over-stretched brain. It sounded as if he was saying this room did not comprise all their home. Victoria slept ou a pull-out bed in her aunt’s lounge. She was not taking it in: she could not. She subsided back into the big chair which was like a hug, and actually put her thumb in her mouth though she was telling herself, You’re not a baby, stop it.

Who else lives here, she wanted to ask, but did not dare. Where are all the other people?

Edward was looking steadily at her, hoping for enlightenment. That anguished little face … those hot eyes … He followed his instincts, went to her, picked her up, cradled her.

‘I’ll tell you a story,’ he said.

And he began on The Three Bears, which Victoria had seen on television. She had not really thought before that you could listen to a story, without seeing it in pictures. A voice, without pictures: she liked this new thing, the kind boys voice, just above her head, and the way he changed it to fit Big Bear, Middle Bear and Baby Bear, and Goldilocks too, while he rocked her, and she was thinking, But I’m not a baby, he thinks I am. As for him, he knew very well what he was holding: this was what he championed, made speeches about in school debates, and what he had recently announced he would dedicate his whole life to - the suffering of the world.

When he finished the story, he was about to ask if she would like a bath, but was afraid she might misunderstand.

‘Have you had enough to eat?’

‘Yes, thank you.’

‘Then I’ll take you up to bed.’ It was nowhere near her bedtime: she stayed up late at home because she could not go to sleep until her aunt did. Or she would fall asleep while her aunt watched television and find herself, still in her day clothes, with a blanket over her, on the day-bed. She held on to the tall boy’s hand and was pulled fast up the stairs, flight after flight, and then she was in a room crammed with toys. Was this a toy shop?

‘This is Thomas’s room. But he won’t mind if you sleep in his bed, for tonight.’

No one had mentioned a toilet and Victoria was desperate. She stood staring at him, a silent phase, and then he said, rightly interpreting, ‘I’ll show you the lavatory.’

She did not know what a lavatory was, but found herself in another room, the size of her bedroom at her mother’s, on a toilet seat of smooth, unchipped white. There was a big bath. She would have loved to get into it: she had known only showers. Edward was waiting for her outside the door.

She was led back to the toy-shop room across the landing.

‘When I go to bed I’ll be upstairs, just one flight,’ said Edward.

Panic. She was being abandoned. Above and below reached this great empty house.

‘I’ll be downstairs in the kitchen,’ said Edward.

Her face was set into an a look of horror. At last Edward understood what was the problem. ‘Look. It’s all right. You’re quite safe. This is our house. No one can come into it but us. You are in Thomas’s room - where he sleeps. Well, when he’s not with one of his friends. You kids certainly do have a lot of friends …’ He stopped, doubtful. He supposed that this child did too? On he blundered. ‘I am here. You can give me a shout any time. And when my mother decides to come home she’ll be here too.’

Victoria had sunk on to Thomas’s bed, wishing she could go down with Edward to the kitchen. But she dare not ask. She had not really taken in that this great house had one family in it. People might easily have a family in two rooms, or sometimes even in one.

‘You’d better take off your jersey and your trousers,’ said Edward.

She hastily divested herself, and stood in little white knickers and vest.

He thought, how pretty on that dark skin. He didn’t know if this was a politically correct thought, or not.

‘Here is the light,’ he said, switching it on and off, so that the room momentarily became a creepy place full of the shapes of animals, and huge teddies. ‘And there’s a light by your bed. I’ll show you.’ He did. ‘I’ll leave the door open. I’ll be listening.’

He didn’t know whether to kiss her good night, or not. Seeing her without her bundling clothes, she was a tough wiry little thing, no longer a soft child, and he said, ‘How old are you, Victoria?’

‘I’m nine,’ she said, and added fiercely, ‘I know I’m small but that doesn’t mean I’m little.’

‘I see,’ he said, knowing he had been making mistakes. Once again scarlet with embarrassment, he lingered a while by the door, then said, ‘I’ll switch this off, then,’ did so, and went off down the stairs.

Victoria lay in a half dark, under a duvet that had Mickey Mouse all over it. She liked that, because she had had Mickey Mouse slippers when she was smaller. But this room, in this half-dark - she did let out another wail and then clamped her mouth shut with both hands. All these animals everywhere, she had never seen so many stuffed toys, they were heaped up in the corners, they loaded a table, and there were some teddies on her bed. She pulled a large teddy towards her, as protective shield against the looming lions and tigers and mysterious beasts and people, their eyes glinting from the light that came from outside. She couldn’t stay here, she couldn’t … perhaps she would creep down the stairs and go back to that place they called a kitchen and ask Edward if she might stay. He was kind, she knew. She could feel his arms tight round her, and she set herself to listen to his remembered voice in the story.

There was another fearful thing she had to contend with. Suppose she wet her bed? She did sometimes. Suppose she walked in her sleep and fell down the stairs. Her aunt Marion told her she did walk in her sleep, and she had been caught, fast asleep, out on the landing standing by the lift. If she wet the bed here, in this place, she would die of shame … and with this thought she fell asleep and woke with the light coming through a window she had not seen last night was there. She quickly felt the bed -no, she had not wet it. But now she wanted the toilet again. She crept out of the room, and in her little knickers and vest ran across the landing to the toilet. She felt like a burglar, and kept sending scared glances up the stairs and down. There were lights on everywhere. What time was it? Oh, suppose she was late for school, suppose … back inside her trousers and jersey, she went down the stairs and saw beneath her Edward at the table, eating toast. There was no sign of the woman with all that golden hair. Edward smiled nicely, made her toast, offered her tea, put the milk and sugar in the way she liked it, and then said he was going to take her to school.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.